Seijun Suzuki is one of the more famous Japanese directors of the ’60s, when younger filmmakers were taking the rein from the older masters like Ozu and Mizoguchi and Japanese domestic cinema was seeing both its high point as a commercial medium, and heading toward a crash in the late ’60s when television would finally saturate Japanese markets. Suzuki worked at Nikkatsu, strangely the oldest and newest Japanese film studio at the time (it was the first film studio in Japan but had been disbanded by the Imperial government in 1941 and reformed 10 years later) whose bread and butter was genre films appealing to youth audiences. It was a studio system as industrialized and formulaic as Hollywood’s Golden Age, with an important difference: as long as they worked within the confines of the genre and provided scripts, executives wouldn’t meddle much with the product. Directors were largely left alone.

This meant that as time went by, directors at Nikkatsu began to use their autonomy to put a personal stamp on their films, and few went to the extremes of Seijun Suzuki. Beginning with iconoclastic art direction and leading to full-blown surrealism in his final film for the studio, Branded to Kill, Suzuki was eventually fired for taking his liberties in 1967.

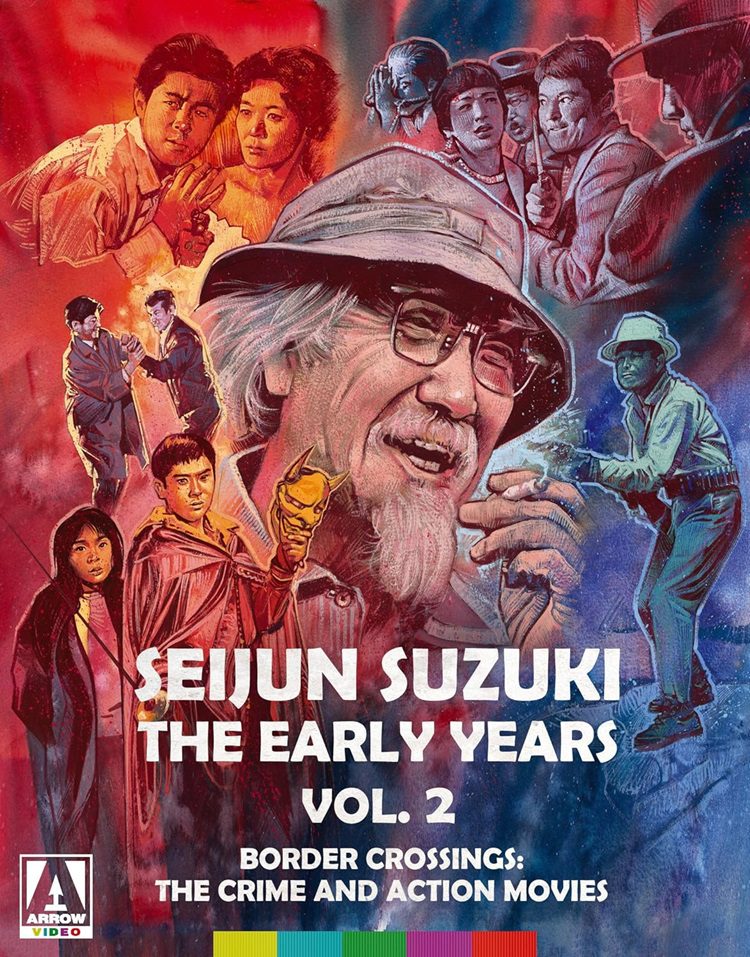

In Seijun Suzuki: The Early Years Vol. 2 Border Crossings: The Crime and Action Movies, the second of Arrow’s retrospective of Suzuki’s work before his creative break-through with Youth of the Beast in 1963, we’re presented with five films from the period before the man went wild. This is, surprisingly, not a substantial chunk of the director’s early output – he made at least 25 films between 1956 and 1962 (six movies in 1961 alone, two of which are in this collection). They were largely programmers, made in a few weeks each and meant to fill double bills for a, at the time, voracious audience. It took time for Suzuki’s individual voice to develop, so these movies, all of which have their own merits, perhaps serve better as an indicator of the studio’s programming pre-occupations than they do an incipient visual maverick’s developing style.

On the first of two Blu-rays are a pair of movies that serve as thematic companions to one another: The Sleeping Beast Within and Smashing The 0-Line, both from 1960. Both films are about newspaper reporters investigating the drug trade, with Hiroyuki Nagato playing very different leads in each film. In The Sleeping Beast Within, he’s Shotaro, an earnest young reporter who is friends with Keiko, a girl who needs his help. Her father has just returned from a business trip in Hong Kong on a final assignment for his work. After his retirement party, he disappear for days. Shotaro helps Keiko search, but when the father turns up alive and well with a facile explanation for his absence, Shotaro keeps running down the clues, uncovering a drug smuggling ring and putting his, and Keiko’s lives in danger.

In Smashing the O-Line, Hiroyuki plays the unscrupulous Katori, who runs in criminal circles and facilitates crimes himself so he can report on the eventual fallout with the police. Both of these films are pretty run of the mill for early ’60s Nikkatsu, featuring location shooting in slummy conditions. They’re energetic and fast paced (as is all of Suzuki’s material) and feature ambiguous endings that were also a staple of Nikkatsu’s noir-tinged crime films.

The second disc has three films, including a pair of what are basically Japanese Westerns, and a Youth movie starring Koji Wada, star of several Suzuki movies in the early ’60s. The first film, Eight Hours of Terror (1958), is probably the most strictly entertaining film in this set. A riff on Stagecoach, the titular eight hours are the time spent on a bus, driving down a dangerous and winding mountain road. The passengers are a diverse cross-section of Japanese society: a rich company boss and his snooty wife, young Communist students, a fresh faced actress going to an audition. They all have reasons they need to get to Tokyo as soon as possible, but the rumors that some bank robbers are on their route makes them jumpy. Terror is a fun, episodic romp where various combinations of characters get to interact in amusing scenes, as it moves from broad comedy to tragedy and crime thriller. Like most of Nikkatsu’s output of the time, there’s a strong sense of social criticism, where the socially upright members of the traveling group are proven to be cowardly or useless in crises, and the lower classes (including a double murderer!) get the group out of jams, save lives, and are just all around keen folks.

Man With a Shotgun (1961) is another Western, set in the Japanese mountain forests instead of the wide open plains. Starring Hideaki Nitani (also a star of one of Suzuki’s last films before he got fired, Tokyo Drifter) as a broken hearted wanderer, going from town to town with his shotgun looking for the men who murdered his wife, he comes upon a small mountain town run by a criminal gang, and quickly becomes sheriff. One of his chief rivals becomes his unlikely ally when the crime boss’s drug fields are discovered, and it all ends in a showdown that for some reason takes place on the beach, far from any environs we’ve seen so far.

The last film on this set, Tokyo Knights (1960), has to my mind the largest hint of where Suzuki was going to take his art. A youth in revolt story starring Koji Wada as the heir to an industrial firm who has spent his youth being educated in America, he doesn’t want to follow in the corrupt ways of his superiors. This marks him out for death by the other industrialists, who get their jobs by making backhanded deals and screwing over their workers. Wada, who plays Koji Matsubara, is impeccable at everything he tries (there’s a comic section at the beginning of the film where every club at the Catholic high school he goes to tries to recruit him, and he bests all their members at their individual sports) and has a deep sense of honor, which doesn’t fit in well in the wheeling and dealing world of Japanese industry. This is probably the wildest film in the set, where the art direction and mise en scene begins to lose the more grounded realism the other films employed. Many scenes take place in a bar room where the backdrop is changed, practically shot by shot, into new artwork and new patterns. There’s a standoff at the school where the fencing and kendo teams beat off hardened gangsters. Koji spends one entire scene like a caped superhero, wearing an oni mask and diving between buildings, stealing cufflinks from his enemies to find the ones that lead to clues about his father’s murder. It may be hard to take seriously, but it’s filled with an infectious sense of fun and playfulness.

These are older films, and so they look on Blu-ray about as good as one could imagine – not perfect looking, being grainy and somewhat faded, but probably as good as it would be possible to get with a bunch old B-movies that were meant to play for a couple of weeks in theater and then never seen again. And though they aren’t lost examples of Suzuki’s later eccentric art and direction style, they are an interesting snapshot of the Japanese film industry at the time. There’s an undercurrent of suspicion of authority, celebration of youth, and a lack of cynicism that would carry on with Nikkatsu for some time… right up until they became, in a cynical and for a time profitable move, mostly an erotica factory, pumping out creepy sex flicks for the dying movie houses.

Seijun Suzuki: The Early Years Vol. 2 Border Crossings: The Crime and Action Movies has been released by Arrow Video on a two Blu-ray set. There are a few extras on the set, including a 50-minute video interview with critic Tony Rayns about Suzuki and these films, a commentary on Smashing the O-line by the always enlightening Jasper Sharp, and a booklet containing an essay by Sharp on, not just Suzuki’s work at Nikkatsu at the time, but the studio and Japanese film system in the late ’50s and ’60s as a whole.