In the opening of Howard Hawks’s gangster film Scarface (1932), we see a title card that notes that the film is an indictment of gang rule in America, and then it deflects any responsibility towards the eradication of gang violence away from the film industry and towards the government. This was added after a long feud between the MPPDA (which became known as the Hays Office) and Hawks (and Howard Hughes, who produced the film). The Hays Office believed the film glorified gang violence and demanded numerous cuts. Some cuts were made, the ending was changed, and finally, the title card added to satisfy the Hays demands.

A little over fifty years later, Brian De Palma remade Scarface (1983) and found himself battling it out with the MPAA over its violence. He submitted the film three times, each time making cuts to the film, and received an X-Rating in each instance. After that, they invited a number of specialists, including DEA agents, to a meeting with the MPAA where it was explained De Palma’s movie, rather than glorifying the violence, actually told it like it is and served as a warning against getting involved in the drug trade. The MPAA relented giving the third cut an R-rating. De Palma then sneakily restored his original cut and released it as is with no one the wiser.

Made in 1932, Hawks’s film is loosely based on the life of Al Capone. It stars Paul Muni as Tony Camonte, an up-and-comer in the Chicago illegal liquor trade. After he murders the South Side crime boss for Johnny Lovo (Osgood Perkins), Tony becomes a lieutenant in the Lovo organization. Quickly, Tony takes matters into his own hands and starts killing off other gangsters, obtaining more power for Lovo (and really himself) in the process. Tony also takes a liking to Lovo’s girl Poppy (Karen Morley) whom he pursues as relentlessly and carelessly as he does everything else in his life.

Meanwhile, Tony’s best mate, Guino (George Raft, using that coin-toss thing he does for the first time), takes a shine to Tony’s sister, Cesca (Ann Dvorak), but the two must meet in secret for Tony is insanely jealous of any man who gets close to her. Tony takes over more and more of the liquor trade, earning more money and power than he could ever use in the process. Instead of making him happy, it only serves to increase his paranoia. He puts steel doors and shutters in his house. He trusts no one. When he declares war on the gang that controls the north side of the city, he incurs both public scorn and more police scrutiny. All of which leads to a bloody showdown.

De Palma’s film follows the basic storyline quite closely but the films couldn’t be more different in terms of style. Hawks’s film comes in at a taught 95 minutes with a script that is tight as a drum. It is full of action, drama, and even a little romance but not an inch of fat. De Palma’s version runs for 170 minutes and contains all of the excesses one has come to expect from the director’s work in the 1980s. It is brash, garish, overindulgent, and unrestrained.

He moves the setting to Miami where waves of Cuban immigrants have just come over after Fidel Castro has opened his borders (and his prison doors, hoping to get rid of a few undesirables in the process). Here, Tony is Tony Montana (a delightfully over-the-top Al Pacino), a refugee who claims to be a political prisoner but is really a guy in search of the American dream, who will do anything to obtain it. After a few killings for hire, he finds himself as the right-hand man to drug kingpin Frank Lopez (Robert Loggia). Michelle Pfeiffer plays Elvira, Frank’s girlfriend; Steven Bauer plays Tony’s best pa;l and Mary Elizabeth Mastratonio is Gina, the sister.

Again the plot follows pretty closely to the original, but with so much more pizazz you might not notice at first. For example, early in the Hawks’s film Tony is hired to kill the leading crime boss of the city. We see it only in silhouette. In the De Palma version, it isn’t so much a hit put out on the boss, but a bad drug deal gone bad that ends with one of Tony’s pals being chainsawed to death followed by a flood of bullets. For another example, late in De Palma’s film, Tony has just killed the wrong guy resulting in a war with his Bolivian distributor. This is just before the famous “Say ‘hello’ to my little friend” line. We see him in his opulent office inside his opulent home. He sits at his fancy desk in his fancy suit with a mountain of cocaine in front of him. He puts his face right into it and snorts, coming up with coke all over his nose and suit.

On and on the changes are made, where Hawks is subtle, De Palma is a sledgehammer. It probably doesn’t hurt that the script was written by Oliver Stone, a man also not known for his subtlety. Where Hawk’s film hints at a possible physical attraction between Tony and his sister, De Palma has Gina at one point open her robe and ask Tony if he wants some. Hawks films in beautiful black and white, keeping his camera close, allowing us to feel boxed in with Tony. De Palma lets his camera sweep over everything, taking in the lavishness. It is full of bright neon colors with huge sets full of shiny gold things. It is overindulgent in every way. It’s also just about perfect.

I love both films. I’d never seen Hawks’s film before but immediately fell for it. I had seen De Palma’s version at least once but I was never overly impressed by it. Having seen most of his ‘80s output now and having come to understand and adore his style, I really got into it on this viewing. It is still perhaps a bit too long, but I couldn’t tell you what I’d cut.

Both films have a great cast. Paul Muni is terrific as Tony in Hawks’s film and while Pacino is as over the top as the film, it works perfectly for what De Palma is going for. Ann Dvorak as Tony’s sister in the Hawks’s version is magnetic. I’d not seen her in a film before but I’m certainly going to look for her in other films now. Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio’s role isn’t as significant as Dvorak’s but she makes the most of it with big hair and bigger emotions. The girlfriends are underused in both films.

Ultimately, I can’t say which film I like the best. This is the perfect material where two films take the same story and make something completely different out of it. In a pinch, I’d probably say Hawks’s version is the greater film as it’s a tighter script, but De Palma’s film is so flagrantly out there I can’t help but admire the gall of it.

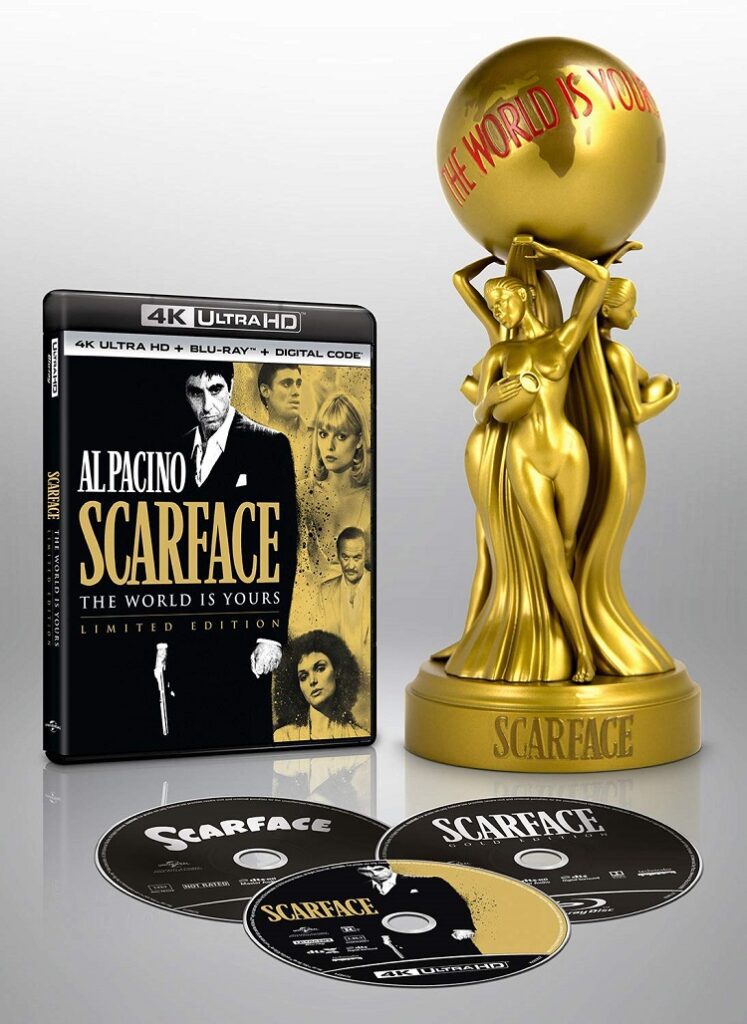

Universal Studios has just released a special edition of both films just in time for your early Christmas shopping. The De Palma version comes with a new 4K Ultra HD transfer (as well as a regular Blu-ray disk) and the Hawks film makes its first appearance on Blu-ray. Extras for the Hawks’s film include an old introduction by former TCM host Robert Osborne and the alternate ending. The new extra on the De Palma version is an interview with the director, Al Pacino, Michelle Pfeiffer, and Steven Bauer for the film’s 35th anniversary showing at the Tribecca Film Festival. Extras ported over from a previous release include deleted scenes, and several making-of features. It also comes with a pretty hefty “World Is Yours” statue that looks great next to my The Big Lebowski bowling ball.

Both versions of Scarface tell a fascinating story about the rise and fall of an ambitious criminal willing to do anything to get to the top and then failing spectacularly. That they tell that story so wildly differently is a testament to the power and vision of both Howard Hawks and Brian De Palma. This is a magnificent set with a wonderful 4K transfer of the De Palma film and a very nice upgrade for the Hawks version. It will make a perfect gift for any cinephile’s collection.