It was not supposed to turn out like this.

For years, the Pitney lumber mill in Maine soaked its river-borne logs in mercury, poisoning the water and wreaking havoc on the ecosystem. Tadpoles are now as big as boots, the salmon even bigger. Then there are the bears—oh God, the bears! They tower. They look like the skinned offspring of a boar and a 20-foot muskrat. And they move like the wind.

On a pushcart.

Told of disputes the mill has had with a local tribe of Native-Americans, Dr. Robert Verne (Robert Foxworth) steps in to mediate. This is a change of pace for him. White-knight savior to rat-bitten babies in the ghetto, he brings his cellist wife, Maggie (Talia Shire). Things between them are tense. He does not want kids; she’s preggo. To complicate matters, they eat fish from the water nearby. Once he discovers the mill’s dirty little secret, more questions arise. How, if they can, do they stop this ecological nightmare? Will their baby be ok? Will it be something it should not?

We never find out—and that is Prophecy‘s best use of suggestion.

Shire pouts for most of the film. In one scene, rain pelts her for what feels like minutes (put your hood on, dammit!). A mutant bear cub maims her as well—but she is not the film’s most galling offense. No, that distinction goes to director John Frankenheimer.

With utter silliness, Frankenheimer, a crack conveyor of nervous paranoia (The Manchurian Candidate, Seconds), cheapens an earnest, socio-environmentally outraged (and pedestrian) script. This dubious honor, ironically, saves the picture. Scattered moments aside, Prophecy sucks. It sucks hard. Yet it is kind of fun.

Much of the time, the moviefeels like a late 1970s TV cheapie that happens to be a Paramount production. Doubling for Maine, British Columbia looks great—but no one shot commands our attention. The production values are slick if unremarkable. Lacking distinctive mannerisms, most of the actors are stuck in the blurry cardboard confines of their characters. As the tribe’s studly leader, a miscast Armand Assante plays…Armand Assante, chewing his lines admirably (he was born to do camp, but he is unconvincing here). As the mill’s director, Richard Dysart excels. (In John Carpenter’s The Thing, Dysart played the guy who lost his hands. In Prophecy, he loses his feet.) He radiates oiliness, suggesting he was the only actor present who was skilled enough to embrace the movie’s roots in bug-eyed schlock without looking foolish.

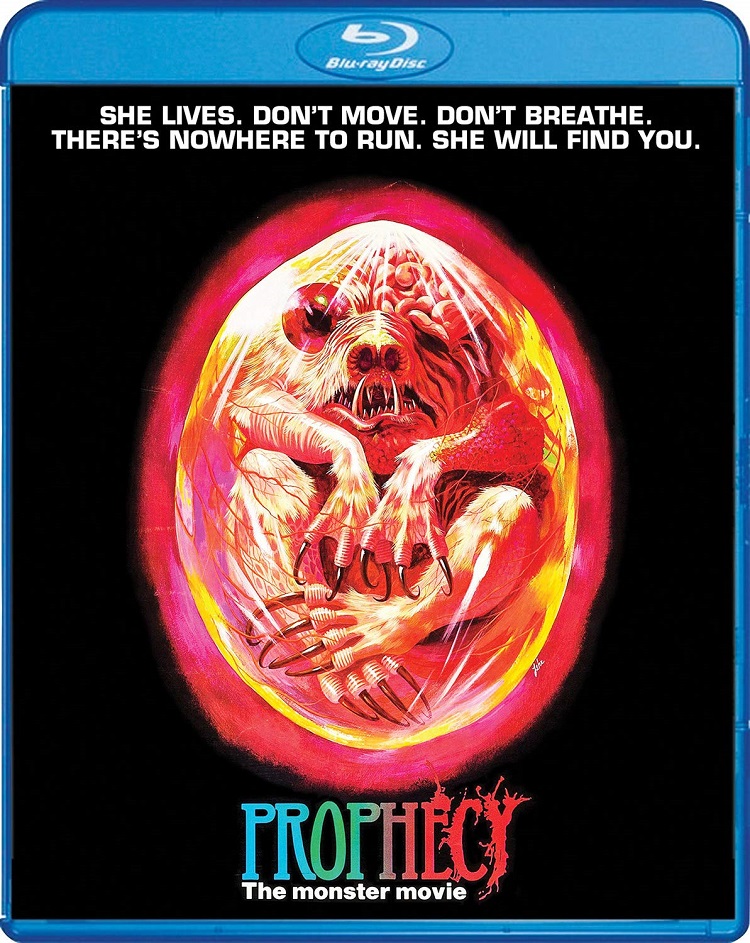

Prophecy wears a noble message on its sleeve. If left unchecked, the teat of big business will destroy our precious natural resources. Mother Nature will bite back. And here, Mother Nature is Katahdin, a spirit-force the tribe holds in awe, and which takes on the outward manifestation of a mutant bear. This is where Prophecy takes off, where believability wanes. Its unintentional humor and absurdity aside, the movie is a cautionary fable that refuses to scare us.

We can blame Frankenheimer (who was reportedly battling alcoholism) for this misguided effort, this failure of execution. But we should credit him (or alcoholism) for the film’s arsenal of jaw-dropping moments: the exploding sleeping bag, the appearance of the mutant cubs (a special effect that rises to Eraserhead levels of disquiet and disgust), the head-munching wait in the tunnel, and the prolonged but oddly static chase across the water. At the end, he throws in a parting trick shot straight from director Brian De Palma’s playbook. Prophecy alsocarries that strain unique to bad horror films: characters who make awful decisions that defy belief. In this movie, the curse is pandemic, amounting to a weird but glorious and mind-melting form of Chinese water torture. All these elements make the picture for me.

And I salute Frankenheimer for putting the monster in my face. This is a film about nature run amok and the toxic effects of corporate blight. A lighter touch could have stoked our imaginations; but no matter how cheesy Katahdin is, the filmmakers wisely figured a payoff was in order for this kind of picture. They had to tease us, then show the monster in time for the climax. An audience in 1979, fresh off the joys of Jaws (1975), might have expected no less of a big-studio horror film. Still, even when it cleaves to the corners of shots, even when shadow partially obscures it, Katahdin is ridiculous. At times you can see the wires in the works. It moves like a tall man in a bear suit—unless the design team sat a model of the bear on a mobile platform, which might explain the floating effect the creature sometimes has. (I kept thinking of Curse of the Demon (1957), how that movie “jumped” the demon in a story whose spookiness relies principally on shadow and suggestion.) Should you be weary of the modern-day glut of CGI, though, the analog, tactile feel of Prophecy‘s special effects does bear some charm (no pun intended).

The Scream Factory Blu-ray is the first I have seen Prophecy. As a Frankenheimer fan and horror maven, I kept an open mind. I kept my expectations low. This, even though (or because) I knew about author Stephen King’s less than muted appreciation of the film in his 1981 treatise on the horror genre, Danse Macabre. I was, in other words, prepared for Prophecy. Depending on your point of view, though, the movie either evolves or devolves into a gross, lame-brained gas.

Was Frankenheimer in on the joke? I doubt it. Sometimes directors lose their touch. Sometimes they make crap, having spun gold for years. And sometimes all the above is true, and they are proud crafts-men and -women who take each job seriously, but not so they would obsess over the finished result. I think Frankenheimer approached Prophecy with degrees of cynicism. The movie packs a few cheap thrills. Beyond that, though, nothing in it suggests he cared about the effect it had on us, only that he and his backers profited. (The film made $23 million against a $12-million budget.)

So, the laughability is a small win. The movie’s chief failing is its chief asset. I cannot say the same for Frankenheimer’s other train wreck of a horror film, The Island of Dr. Moreau (1996). But that is a story for another day.

The Scream Factory release sports new interviews with Talia Shire (very earnest indeed), Robert Foxworth, writer David Seltzer, special make-up effects designers Tom Burman and Allan Apone, and mime artist Tom McLoughlin.