Written by Kristen Lopez

“Each of us is responsible for our own happiness,” says television producer and impresario Norman Lear. And Lear, 90 years young, has found plenty of happiness in his own life that it’s hard to fathom all the additional happiness he brought to others with his television shows, capturing hearts and opening up minds.

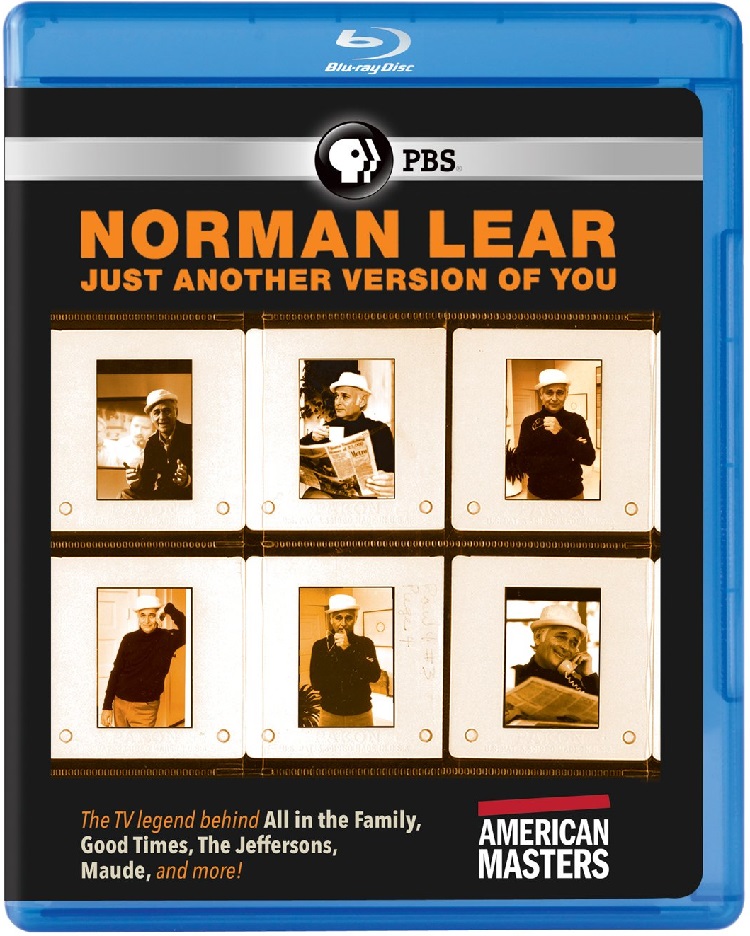

It’s said there was a time “before Norman” and “after Norman,” and in Norman Lear: Just Another Version of You audiences see what the world was like, both before and after Lear’s ground-breaking television shows asked audiences to think and act. His socially critical and controversial television shows – All in the Family, Maude, Good Times, and The Jeffersons – brought new stories into people’s homes, giving them points of view they’d never seen before.

Lear grew up watching his father go to jail under shadowy circumstances. “At nine I was forced to become an adult, but that kid still existed inside me” and a child representation of Lear depicting the events the producer attacked with his child-like whimsy are represented throughout Lear’s story. Shuttled from uncle to uncle before settling with his grandparents, it’s no wonder so many of the shows he concocted dealt with the inner fractures of the nuclear family. In many ways, All in the Family’s Archie Bunker (played by Carroll O’Connor) was based on Lear’s father; he was a man who loved his child, but who, too often, devolved into violence and prejudice.

Bunker was a means of exorcising Lear’s past demons while allowing others to laugh at people’s ignorance. When shown an impassioned speech O’Connor’s Bunker gives about his father, Lear fights back tears and admits there are still old wounds buried deep in regards to his family. Lear also provides wistful reminisces about O’Connor, admitting the two butted heads frequently. In one of many sobering acceptances of death Lear poignantly asks how O’Connor would feel about the current political troubles of today.

But other than a means of reconciling with his past, Lear’s shows were created in the hopes of waking people up. His shows came out during a time of revolution and questioning about government, social issues and the distinctions between people. “Human beings are a little foolish [and] that knits us together.” All in the Family, with its conservative vs. progressive characters arguing over things affecting the average Joe right outside his front door, was subversive enough to put Lear on President Richard Nixon’s infamous “Enemies” list.

Other series, like Maude, tackled feminist issues including abortion and racial complications and it was in regards to the latter where Lear wasn’t quite one with popular opinion. What the cast of the African-American sitcom Good Times says about him and his inability to see past his own white privilege clashes with Lear’s own thoughts about the difficulties the cast provided. Ultimately, he tried to rectify the issues they brought up regarding the portrayal of African-Americans with The Jeffersons.

Despite his shows’ emphasis on blue collar workers and social issues, his work has a lasting appeal. Interview subjects like George Clooney and Russell Simmons discuss how Lear’s shows opened a dialogue regarding race and class, while comedian Amy Poehler’s devotion to Lear – even naming her son Archie – demonstrates the formative group of people “raised” by Lear’s on-screen families.

Lear’s off-screen family may lack the controversy of the households he created but there’s no denying their warmth. His first wife, Frances, was a feminist and manic depressive whose split from Lear broke his spirit. Later, humor rises as Lear recounts becoming a father again over the age of 65. But it’s hard not to imagine how fun his past parties were. His sit-down with Mel Brooks and Carl Reiner, two frequent visitors at his house, leave you hoping to be a fly on the wall. None of these three have lost their bluster and it’s pure joy watching them reminisce and enjoy their time together.

To Lear, others around you change with age, not yourself, and Norman Lear hasn’t lost any of the traits he started out with. Norman Lear: Another Version of You presents all the versions we’ve come to identify with – Lear the producer; Lear the activist; and we also get Lear, the man, which is the best of them all.