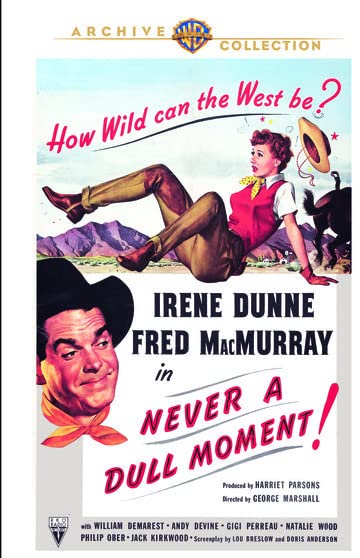

Based on the 1943 book Who Could Ask for Anything More? by composer Kay Swift ‒ best known to today’s “classic” music enthusiasts (read: people who hang out in jazz bars) as the composer of the timeless standard “Can’t We Be Friends?” ‒ 1950’s Never a Dull Moment finds Irene Dunne as Kay Kingsley: a fictionalized variation of her real-life counterpart, who, as our story opens, is a popular singer/songwriter in bustling New York City. During a charity rodeo event (in NYC) she helped to organize, she catches the eye of a simple, widowed father of two cowboy/rancher named Chris Heyward (Fred MacMurray), whose loudmouthed colleague (the great Andy Devine) promptly eschews all formalities within the confined classifications of contemporary society and introduces the two to each other.

Within a matter of days, Kay and Chris have tied the knot and are on the way to Chris’ rural ranch way out west in the middle of nowhere. It is there that we begin the basic premise of Never a Dull Moment: that of a woman accustomed to life in The Big Apple (with servants, probably) becomes the proverbial fish out of water as she suddenly becomes a housewife and mother to two growing girls (played by the pairing of youngsters Gigi Perreau and Natalie Wood!) who aren’t readily committed to accepting a new mother figure into their lives. And so, we witness Dunne (who took over for Myrna Loy, presumably when the latter remembered she had left the gas on) learning to ride a steed, putting up with the most insultingly non-Native American Native American servant ever (Margaret Gibson, giving Shriek of the Mutilated‘s Ivan Agar a run for his money), and butting heads with ornery ol’ William Demarest.

Reportedly the winner of the Harvard Lampoon’s “Dullest Movie Award,” Never a Dull Moment comes dangerously close to being a cinematic oxymoron in many respects. Its tale is as cliché as can be, bordering on the frayed edges of being an unsold pilot to what would have become a short-lived sitcom throughout. (In contrast, good guy Fred MacMurray and his onscreen enemy William Demarest would later be paired together ‒ this time as close-knit family ‒ on the long-running My Three Sons when the latter took over for an ill William Frawley.) This epitomizes itself roughly around the time Andy Devine gets rolled up in fencing and Ms. Dunne bakes biscuits that look like enormous mushroom stems ‒ to say nothing of the part where she bags what she believes to be her first cougar (something I’m quite proficient at, but in an entirely different, decidedly more “urban” vein).

Nevertheless (yes, I went there), this silly little comedy from the beginning of a decade best-remembered for steak breakfasts, martini lunches, and dinner at the drive-in carries with it a certain amount of (admittedly, dumb) charm. In a way, it could very well have prepped Mr. MacMurray for his future career as one of television’s foremost father figures. The movie also (sort of, kind of) serves as an opening ceremony for the slew of rodeo and western tales that would follow in the ’50s ‒ from dynamic western noirs such as The Lusty Men to even duller messes like Sky Full of Moon ‒ as well as the kiddie cowboy craze that ensued when youngsters realized they could watch westerns at home on the TV; something that would receive a lampooning of its own in Callaway Went Thataway, which also featured real life rancher Fred MacMurray.

The Warner Archive Collection lassoes this all-but forgotten situational comedy from yesteryear, preserving the photoplay in its original 1.37:1 aspect ratio on a barebones Manufactured-on-Demand DVD-R with mono 2.0 sound. I noticed the volume on the audio went up a few notches in a scene where all of MacMurray’s ranchhand buddies invade the bedroom one morning, so be prepared for that. Unless mine was a mere fluke, or one of the cats jumped on the remote control right next to me when I wasn’t looking. That, or the ghosts of the men and women who had given a solid couple of days’ work (at the very least) for the development of this motion picture ‒ which actually did make its money back at the box office, according to the records ‒ put forth their collective ethereal energy in a vain attempt to get me to pay better attention to the flick.

Alas, no matter what the case, it would have to be classified as an instance of “too little, too late” since ‒ despite there never being a dull moment in Never a Dull Moment ‒ the film doesn’t have enough momentum to captivate even the dullest of rodeo audiences.