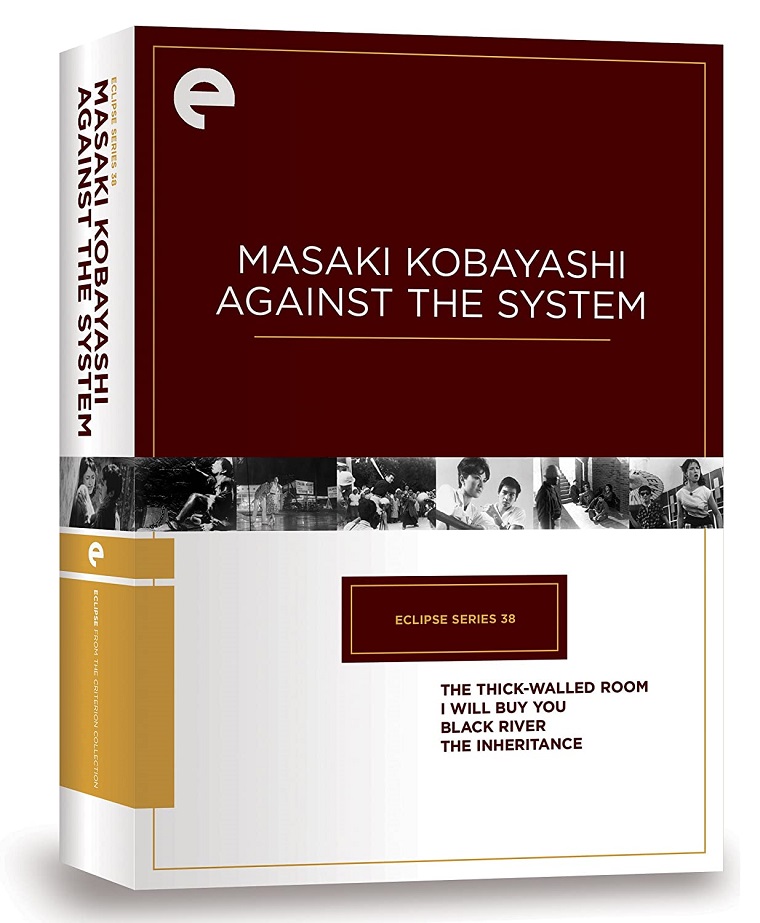

Known for his exemplary samurai film Harakiri and three-part World War II humanist epic The Human Condition, Masaki Kobayashi wasn’t afraid to criticize the cultural values of his country, whether medieval notions of honor or more contemporary militarism. In the four films included in the Criterion Collection’s 38th Eclipse set, Kobayashi’s rancorous tendencies are laser-focused on a host of postwar moral turpitude, both small- and large-scale. These three early works and one from Kobayashi’s prime are angry yet elegant, politically charged but not overtly polemical.

Leading off the set is Kobayashi’s first major film, The Thick-Walled Room, shot in 1953 but shelved for three years by studio Shochiku due to government censors worried about the film’s anti-American content. The film isn’t too concerned with condemning the United States though (the amusingly bad American accents dubbed over the Japanese actors make the U.S. soldiers seem more goofy than anything); it saves its vitriol for a Japanese military system that made its lowest ranking members the fall guys in the aftermath of WWII.

Based on actual prisoner diaries, the film tells the tale of a group of accused war criminals, whose experience in prison is at turns harrowing and enervating. Kobayashi’s camera work is often unbearably intimate, telling personal tales with institutional implications. The film’s imagery varies from documentary-like realism to intensely expressionistic depictions of psychological torment. Its episodic structure culminates in a heartbreaking final act, when one prisoner discovers life isn’t going to improve even outside of the confining prison walls.

Next up is the less compelling I Will Buy You, which suffers from a static shooting style and a too deliberate pace in its takedown of the greed inherent in major athletics. As a critique of Japan’s massive baseball industry, the film succeeds, but seldom have backroom dealings been this free of intrigue.

Nearly all of the forces surrounding star college baseball player Goro Kurita (Minoru Ooki) are corrupt, from his slimy mentor Kyuki (Yunosuke Ito) to ambitious scout Kishimoto (Keiji Sada), the narrator who gleefully admits his willingness to do anything to sign the promising prospect. Kobayashi would make a more narratively and visually engaging film about a struggle to be the king of the cesspool with the last film in the set.

Black River is a bit of a stylistic outlier; its ragged jazz score and looser shooting style fit the material well. Examining the widespread societal moral decay in postwar Japan, the film focuses on matters of love and business. In a decrepit neighborhood on the outskirts of a military base, a love triangle forms around the comely Shizuko (Ineko Arima). She’s courted both by serious-minded student Nishida (Fumio Watanabe) and up-and-coming yakuza member Joe (Tatsuya Nakadai); the moral dichotomy seems clear on paper, but Nishida isn’t exactly a saint. Consider a disturbing scene where no one will step up to donate blood to a man in the throes of death.

The film’s other major element concerns a shady landlady (Isuzu Yamada), whose plan to destroy the building of her tenants for profit is as ugly as her crooked teeth. Black River almost feels post-apocalyptic at times, its dingy, dramatically lit images revealing a world where the line between the haves and the have-nots is becoming sharply divided, and total societal chaos doesn’t seem far off.

The set finishes with a later film, 1962’s The Inheritance, which directly precedes Harakiri in Kobayashi’s filmography. The two films’ widescreen images share a stately, measured elegance that stands in stark contrast to their twisted content. In The Inheritance, a wealthy businessman (So Yamamura) announces his death is imminent and asks his associates to locate his three illegitimate children so the estate may be divided up among them. The cadre of lawyers, colleagues and his much-younger wife (Misako Watanabe) set out to ostensibly fulfill his wishes, but in reality, scheme to line their own pockets. But none of them may be able to match wits with his deceptively clever secretary (Keiko Kishi).

The Inheritance possesses some of the same static qualities as I Will Buy You, and its excoriation of greed is often very similar, but it’s a more accomplished film, often thanks to Kobayashi’s interior photography, where clean lines and crooked people are framed together in a series of brilliant compositions.

Like all Eclipse sets, this one comes sans bonus features, save for the concise and precise liner notes from Michael Koresky. The transfers, especially The Thick-Walled Room, are a bit rough around the edges, but generally very clean.