Director Sam Peckinpah was a few things: a drunk, misogynist boor; an auteur who was always getting screwed by the studios and producers he kept disappointing; and a guy whose best work fed off his self-destruction and the meddling of others.

And let me tell you. Between 1969 and, oh, 1975, he made some great films.

Major Dundee (1965), though—his trial run for The Wild Bunch (1969)—is not one of them. None of the reassessments it’s received can convince me otherwise.

So, what is Major Dundee then?

I have a few thoughts:

The most obvious is—this was Peckinpah’s first shot at an epic, big-studio Western. Prior to Dundee, he’d made a couple smaller films (Ride the High Country is the gem of the two) and was preparing One-Eyed Jacks, which Marlon Brando directed. Dundee is also the first Peckinpah film a studio butchered behind his back. By that point, though, no amount of fussing and fiddling (trimming about 40 minutes and adding a cutesy, chintzy score, with a song by Mitch Miller’s Sing Along Gang, that drove Peckinpah nuts) was going to save it. On set, Peckinpah had acted badly, drunkenly; and, after producer Jerry Bresler fired Sam, the film’s star, Chuck Heston, forfeited his salary to keep things running. Any gap in continuity, in ‘vision’—any conviction the egos involved had that the film was screwed—was bound to seep into the final product. Or… So I’d like to think.

What else? Well, Dundee tackles some serious concepts. And if Peckinpah didn’t mean it to be a Vietnam allegory, with more than just a touch of Moby Dick, you can read it as one.

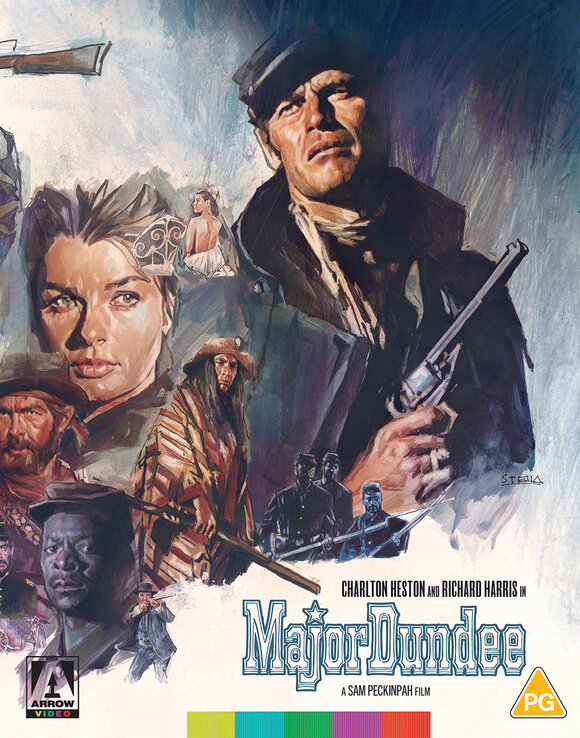

The story is simple: Civil War foes team up to cross the border and hunt down the ‘devil’ Apache that raided a village and kidnapped some kids. Leading the charge is Major Amos Dundee (Heston), a disgraced Union officer who recruits a ragtag group of alpha males (and we have a whole mix here—jailed Confederates, Union soldiers both white and black, and other, assorted riffraff) to join him on an Ahab-like quest to get the Apache—and to clean his name. Dundee’s furious, relentless pursuit makes for all kinds of tension between the men. And his wild bunch is a crop of outstanding character actors with amazing faces (many of whom starred in other Peckinpah films): James Coburn, Ben Johnson, L.Q. Jones, Warren Oates, and Dub Taylor. Foiling, or threatening to foil, Dundee’s cause is Confederate Captain Ben Tyreen (Richard Harris). Tyreen and Dundee go back a ways and share a lot of bad blood. But Tyreen is also someone that Dundee respects, and the love/hate might be mutual.

Let’s pause to draw some comparisons with The Wild Bunch, a film that Dundee foreshadows. Both films take a tough look at the group dynamics of a fierce (and you could say fated) band of warriors who decamp to a glorious but pitiless Mexican landscape, where they make one last bid for glory (however shot full of holes that concept of glory is). Both films have a colorful cast of characters, and both get bloody. It’s just that The Wild Bunch, as it gets juiced on massacre, takes it to a whole other level; and Peckinpah amps everything in that picture. His flow is better. He gets stone drunk on the rank, everything-is-broken beauty of violence and death, and he’s obsessed with the way a certain man holds true to his word, and his world, and the way he chooses to die. All this peaks in The Wild Bunch. Dundee, by contrast, is tame. Peckinpah hadn’t yet sealed his signature style of the slo-mo death ballet. So, while the action scenes in Dundee don’t flatline, they don’t pop like they do in later Peckinpah. Back to that question of pacing and flow, though: It’s when the Major goes on a bender in Durango that the movie loses its way. The director wants us to feel low like the Major, to be bummed out; but we just get antsy. We wait for the character, and the film, to get going again—to rouse itself to an awesome conclusion instead of chasing its tail long after we’ve gotten the point (if Peckinpah wants us to have the same fatigue as the characters). This interlude in Durango is the bulk of the restored footage in the 136-minute cut. It deflates the movie, and when Dundee ends abruptly, we can’t help but feel cheated. The Wild Bunch was a vast corrective.

This tells me that Peckinpah was still honing his style; that he needed the ‘failure’ of Major Dundee to come back even stronger. 1965 and Columbia Pictures weren’t ready for him, and neither was he. He needed this setback—and the freedom of the ratings system, and the absorbed inspiration of filmmakers like Sergio Leone (Italy) and Akira Kurosawa (Japan)—to make brazen the John Ford model. He needed an audience jaded by assassinations, racial strife, and stupid, televised wars. An audience that had seen its fair share of ever-lingering PTSD and was ready to explore the old myths in new ways. If that’s a pretentious stab at explaining the Peckinpah magic, so be it. Still, prominent artists don’t happen in a vacuum. Courage, talent, timing, and influence (and hard work) all contribute to the brew. And some of us miss the window.

Peckinpah almost did, but he didn’t give up.

So, Major Dundee is a transitional piece. If you’re into Peckinpah like I am, it has at least a sliver of historical value.

You’ll groan, though. Even as you can see glimpses of the pessimistic, myth-busting wonderland of ’70s cinema to come, the movie has some lame holdovers from the world of the trad Hollywood Western. Many of the side characters are one-note in conception. You get the naïf narrator (Michael Anderson) who becomes a man over the course of the film. You get the clunky, inexperienced officer (Jim Hutton) who learns to loosen up. Adding tired and too-cool-for school dollops of peach-colored Eurotica is Senta Berger, who plays a sexy expatriate doctor. Then we have the Dixie dicks loaded with good-ole-boy schtick. The sum of this is we see a lot of pat characterization next to the film-long standoff between Dundee and Tyreen. As a one-armed mountain man, James Coburn oozes cool, but he’s wasted by the fake beard he has to wear. What a pity it would have been had Peckinpah’s directorial career ended here. At the time, Major Dundee must have felt like a new American Western. Not as corny, comic, or soft (in a word: stillborn) as most of the Hollywood pack, but still under the shadow of the stylish Westerns coming out of Europe.

(And if you decide to trade me Major Dundee for John Ford’s The Searchers, which it echoes, you could make a case for Ford himself as a pioneer of this new Western.)

If Peckinpah is one reason to see Major Dundee, consider this: Heston wins the film. I know—his delivery can be a little camp sometimes. But he’s a bad-ass here. So much so, in fact, that I wasn’t prepared for it; I thought he’d be the weak link. Aside from Oates, none of the other actors match his energy, that gravitas which is the fulcrum needed for everyone else to actualize from and act against. Without Heston’s authority, without that tense chemistry he has with Harris, Major Dundee wouldn’t work.

For Peckinpah fans, the film is a flawed curio—beautifully shot, and showing traces of a gritty, Dirty Dozen-like actioner that never gets too pious or preening for its own good—but it’s still just a warmup for things to come. For Heston fans, though, the movie is something else. It’s a chance to see Chuck riding tall in the saddle and taking crap from no-one.

It deserves to be seen.

The good folks at Arrow Video did right by Major Dundee. The Blu-ray has a 60-page booklet, a fold-out poster, and a panoply of extras. The extras include film historian audio commentaries, a feature-length documentary, and outtakes and deleted/extended scenes. Most significantly, the Blu-ray has the 122-minute, theatrical version of the film, and the 136-minute cut with a new score by Christopher Caliendo. It’s a treat.