Written by Michael Frank

Though norteño music will be new to many who stumble across Netflix’s new documentary, Los Tigres del Norte at Folsom Prison, it has been a staple of Mexican culture for decades. Los Tigres del Norte, a family band that has popularized an entire genre of regional music by releasing over 50 albums, have been family picnic regulars of Mexican-American households since the early 1970s. The San Jose natives travel to Folsom Prison, a California institution that is famous for visitors, not inmates.

Los Tigres, or “little tigers” as they were known by immigration officials, are beloved for singing songs, rather ballads, detailing the roadblocks of being a Latino in North America. They speak of crime, poverty, immigration, drugs, and the common plights of those who have long existed glued to the margins. It’s understood early on in the documentary, helmed by director Tom Donahue, that the band idolizes Johnny Cash, and are inspired by his own performance at the prison. They even sing a version of “Folsom Prison Blues”. Los Tigres understood the rapidly digressing prison demographics, the wavering political climate, and the need for speckled enjoyment at Folsom, opting to play in the main prison yard instead of Cash’s cafeteria.

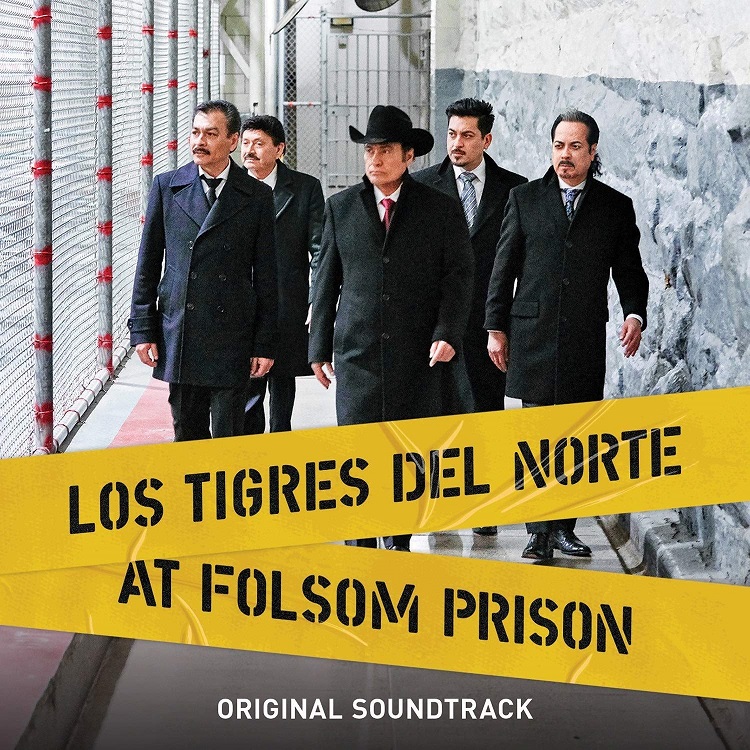

Almost 50 years after Cash recorded his hit live album at Folsom Prison, Los Tigres return to the hallowed grounds with accordians in hand and guitars strapped tightly to their backs. They’re older men now, looking back on careers spanning 50 albums, amassing at least 30 million records sold, and nabbing several Grammy awards in their spare time. Throughout the film, we see snippets of their time spent with the inmates outside of the concert, time they spent praying, listening, and hugging. Fair warning: lots and lots of hugging in this doc.

The documentary, a 94-minute drawl, plays like a concert, sparse with intermittent talking heads and a plethora of musical footage. The band sounds fantastic and you can’t help tap your foot and bob your head to their story-heavy performance. The lyrics are on-the-nose almost to a fault, focusing on the destruction of their melody-constructed heros, while the prisoners dance along with smiles that look more real than staged. Think about that for a second. These prisoners, many of them locked up for life for crimes as heinous as murder, are finding immense joy in the saddest lyrics I’ve heard in a film centered around a concert. And this film isn’t about Los Tigres, it’s about the inmates, their stories, and their relationship to music and an overwhelming sense of collective heritage. These talking heads rips out the edges of your heart, yet leave you with a profound sense of inspiration and hope.

Before this documentary, I had never heard of Los Tigres del Norte. They sing of experiences that I haven’t encountered, of situations and heartbreaks I haven’t suffered. None of that matters, though. Los Tigres aren’t Johnny Cash, and they don’t have to be. They’re a symbol of promise, people with everything that are writing for people with nothing. This documentary is manufactured and recycled from other films, other concerts, and other prison performances, but the weight of it doesn’t and shouldn’t shrink. Donahue’s direction isn’t flashy or expert, but he does allow the audience to take in a bit of the breadth of similarities of Latino and Latina shared experiences. He gives the Folsom inhabitants room to ramble, and for that, he should be proud.

Watch this documentary. It’s short, sweet, and from a perspective sorely needing a spotlight.