Given that even the cheapest films produced today can be presented in faux widescreen with 7-channel surround sound and special effects manufactured entirely via computer software, it’s extremely easy to take some of cinema’s most important milestones for granted. Much like the very first motion pictures to be shot digitally as far back as the early 2000s have already faded from the memory of the general public, the movies which introduced the world to surround (let alone stereo) sound and the phenomenon once known as CinemaScope have become little more than mere footnotes in cinematic history.

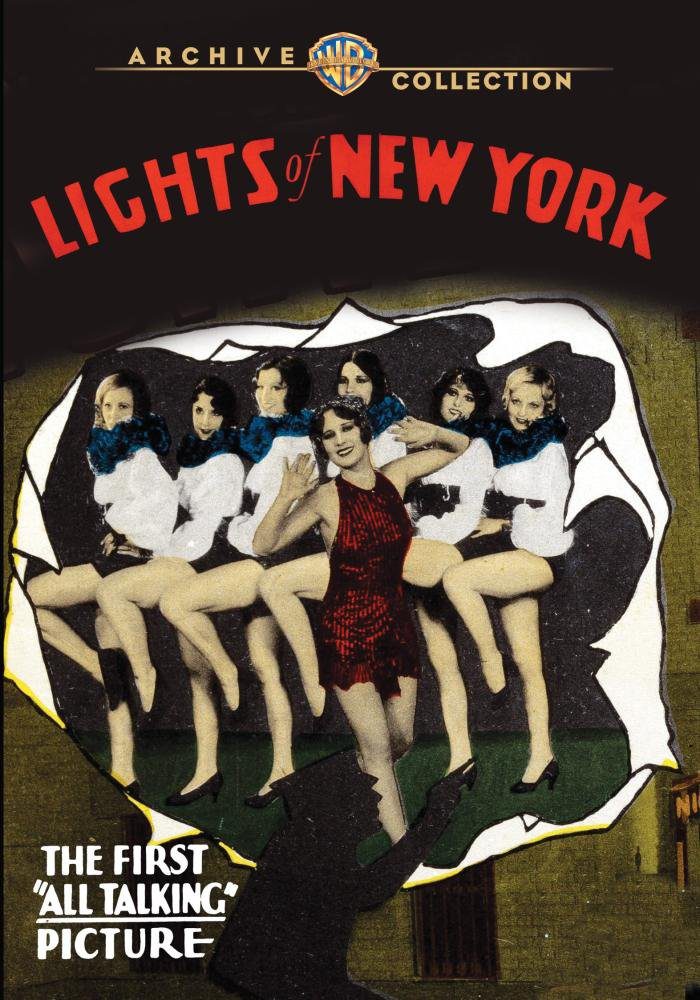

One such milestone ‒ perhaps the greatest since the advent of moving pictures themselves ‒ recently emerged on DVD-R from the Warner Archive Collection. At first glance, the artwork for 1928’s Lights of New York ‒ which proudly promises audiences “The First All-Talking Picture” ‒ seems to contradict Warner Bros.’ previous milestone from 1927, The Jazz Singer. Whereas that aforementioned Al Jolson masterpiece did indeed feature partial sound, it wasn’t until short subject filmmaker (and former child performer) Bryan Foy directed his first feature-length film that audiences would be treated to the first feature-length film with full sound.

As for the film itself, well, there’s nary a living being on this planet who will praise Lights of New York for its plot. Or the way in which Mr. Foy presents it, for that matter ‒ particularly when Bryan occasionally returns to his Vitaphone short subject roots to focus on several elongated musical numbers, none of which are capable of holding anyone’s interest. The story here follows Cullen Landis (who retired from acting after the Silent Era concluded to direct shorts for Jam Handy) and his pal Eugene Pallette, who unknowingly open up a barbershop which actually turns out to be a front for a speakeasy (the very mention of which should give you an idea how dated this one is).

Top-billed actress Helene Costello portrays Landis’ girlfriend here, who works at a nightclub run by prominent gangster nicknamed The Hawk, as played by Wheeler Oakman. It should be noted the latter performer has one of the most outrageously elongated death scenes this side of an early ’70s Turkish revenge flick. Naturally, The Hawk is the same ne’er-do-well who runs the speakeasy Landis is in danger of landing in hot water over. Were that not bad enough, he also has his wandering (hawk)eye on the charming young lady with better billing. Silent screen legend Mary Carr (who later appeared in several Laurel and Hardy vehicles) co-stars as Landis’ mum, and Robert Elliott is a detective on the case of several missing cases of illegal hooch.

When Lights of New York premiered in 1928, it didn’t necessarily strike the fancy of critics, but that didn’t stop the very modestly-budgeted ($23,000) 57-minute feature (which was initially supposed to be a two-reeler before Foy and Co. decided to expand it to take full advantage of the fact studio bosses were out of the country; a crafty venture which almost backfired, as studio execs nearly scrapped the project over how mundane the actual film was) would become an unexpected hit at the box office, where it raked in $1.2 million for its sheer aural innovativeness alone. Or course, were it not for this humble beginning from the man who concluded his career with several more cinematic milestones at once with 1953’s House of Wax, the first major color 3D movie with stereophonic sound, the Sound Era as we know it would not exist.

Of course, stereophonic sound was still nothing more than a dastardly dream from the far-reaches of “the science” when Lights of New York was made. Recorded on Vitaphone’s sound-on-disc format (look closely enough and you’ll spot a few microphones hidden in all sorts of places), it makes a great companion piece to the many Vitaphone Varieties the Warner Archive has assembled over the years. In fact, four of those vintage shorts are included here as special features, presumably to make up for the fact Lights of New York clocks in at just under an hour. As for the feature film itself, the Warner Archive Collection presents Lights of New York in its original 1.37:1 aspect ratio with mono sound, neither of which disappoint considering their age and origin.

As I less-than-subtly hinted at earlier, Lights of New York offers very little in the way of story(telling) which is wholly unique. Apart from Wheeler Oakman’s badly-acted death scene, there’s a couple of (good) shots that succeed in standing out, but that’s really about it. That said, however, just knowing you are watching the very first all-talking motion picture brings with it an undeniable aura of sublime satisfaction, which is present throughout the entire film. I found myself particularly starstruck when I came to the realization the distinctive froggy voice of Eugene Pallette (The Adventures of Robin Hood, My Man Godfrey) ‒ a personal favorite of many a classic movie lover ‒ was the fourth actor to speak out loud in the first all-talking feature.

In short, one should see Lights of New York for what it is, rather than what it isn’t. It isn’t good, by any means, but it is definitely ‒ most-assuredly ‒ a genuine motion picture milestone.