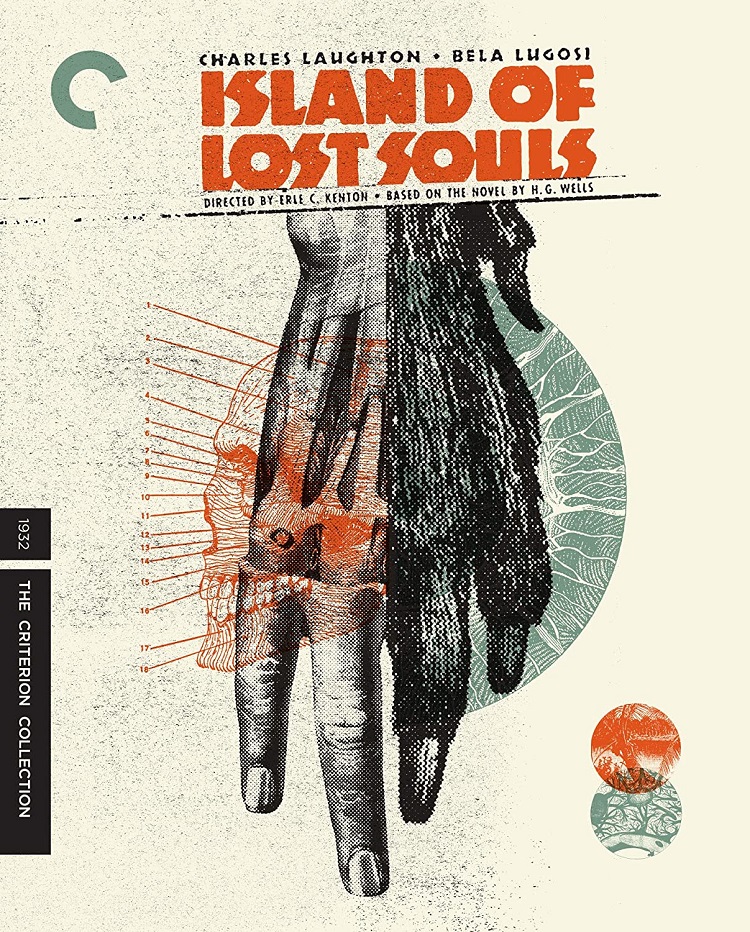

The first of many adaptations of H.G. Wells’ novel The Island of Dr. Moreau, Erle C. Kenton’s Island of Lost Souls is a fascinating blend of science fiction and horror from the pre-Code days of Hollywood. The film leaves a lasting impression on a number of fronts as it takes viewers to a mysterious island where Dr. Moreau (Charles Laughton) defies the laws of nature with his experimental work.

Going from an adventure off-screen to this one, Edward Parker (Richard Arlen) is found floating in the ocean after surviving a shipwreck. A freighter, rendezvousing with a boat from Moreau’s Island, rescues him, but after standing up to the freighter’s drunken captain (Stanley Fields) because he picked on an odd-looking fellow, Parker finds himself forced to leave (in an unintentionally funny moment when an obvious dummy is thrown overboard) with Moreau’s boat.

After learning of Parker’s arrival, Moreau introduces him to Lota (Kathleen Burke, though she’s billed as “the Panther Woman” in a bit of showmanship to make the creatures more believable) to see how they will act towards one another. While sharing a moment together, they hear screams from what Lota refers to as the House of Pain. Parker worries he’ll be next and flees into the jungle where he runs into some of the half animal/half man inhabitants of the island. He is rescued by a whip-cracking Moreau and sees the creature known as the Sayer of the Law (Bela Lugosi) step forward to recite the laws they live by, such as not to walk on all fours, not to eat meat, not to spill blood.

Moreau reveals to Parker he has been working on making animals evolve into people but keeps secret that Parker is part of an experiment as well. Once Parker learns of this, he tries to escape again. Moreau, who thinks himself a god toward the creatures, orders them to capture Parker, but when they see him breaking the laws, they question his authority.

As the best horror does, Island of Lost Souls provides thoughtful reflection on humanity (“Are we not men?” the Sayer of Law asks.) through the use of monsters, though the real monster of the story is one who looks most human. Wally Westmore’s make-up is outstanding as is Karl Strauss’ evocative cinematography. Laughton’s scene-chewing performance of the mad scientist is memorable and Lugosi, under a face full of fur, reveals how underrated an actor he was in a small role.

The video has been given a 1080p/ MPEG-4 AVC encoded transfer displayed at 1.33:1. According to the liner notes we are lucky to have a copy that looks this good “because the original negative no longer survives, this new digital transfer was created from a number of sources, including 35mm fine-grain master positive with some inherent damage; the UCLA Film & Television Archive’s 35mm nitrate positive, which also had defects but contained lines of dialogue not heard since they were censored upon the film’s theatrical release; and a private collector’s 16mm screening print, used to help repair scenes with missing frames and scratches. These elements were scanned in 2K and HD resolution on a Spirit Datacine and a SCANNITY film scanner, and then combined to create the most complete version of the film ever to appear on home video. Finally, thousands of instances of dirt, debris, scratches, splices, warps, jitter, and flicker were manually removed using MTI’s DRS system and Pixel Farm’s PFClean system, while Digital Vision’s DVNR system was used for small dirt, grain, and noise reduction.” Damage is evident and flicker can be seen. There are soft spots, likely due to the source, and whites appear slightly blown out. Film grain can get pervasive, such as occurs during the opening sequence due to soft focus and fog.

The audio is LPCM Mono and the liner notes reveal “the original monaural soundtrack was remastered at 24-bit from the collector’s 16mm print and section of the 35mm nitrate print, the best sources available. Clicks, thumps, hiss, and hum were manually removed using Pro Tools HD. Crackle was attenuated using AudioCube’s integrated workstation.” Hiss can be heard throughout on the track.

Criterion offers a few special features to enhance the film, all in HD unless noted. “Landis, Baker, and Burns” (17 min) – gathers director John Landis, award-winning makeup artist Rick Baker, and horror-film aficionado Bob Burns to discuss the film, those involved in its production, and the era. Film historian/documentary filmmaker “David J. Skal” (14 min)provides great insight into the themes of the book and the era it was written. Filmmaker “Richard Stanley” (14 min), who was he original director of The Island of Dr. Moreau (1996) before he was fired after a few days of production, discusses Wells’ work, the films made from it, and what he was going to do with his version. He even offers an apology for the film that was made, but that’s certainly not his fault.

Gerald Casale and Mark Mothersbaugh (20 min), founding members of Devo whose first album uses the phrase “Are we not men? We are Devo”, talk about the film, horror host Ghoulardi, their time at Kent State, and how the ideas of film made their into their band and music. The “Short Film” (10 min, 1080i) “In the Beginning Was the End: The Truth About De-Evolution.” is an extended music video that features “Secret Agent Man” and “Jocko Homo”. Both are outstanding features for Devo fans.

There’s also a commentary track by writer/film historian Gregory Mank recorded in June 2011. The original trailer (2 min), a Stills Gallery, and a 12-page booklet featuring Christine Smallwood’s essay “The Beast Flesh Creeping Back”.

Island of Lost Souls is a great addition to the video library, especially for horror fans. Owning a copy should be the law. If you don’t believe me, listen to the men like Landis and Baker in the special features.