Bob Dylan had just rewritten his own rules and those of nearly every other popular musician as well by abandoning the confines of acoustic folk in favor of amped-up rock and roll. Having pissed off the folk-movement purists with his infamous “electric” set at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival and defying every fathomable songwriting convention with Bringing It All Back Home and, then, Highway 61 Revisited (which boasted the epic single, “Like A Rolling Stone”), Dylan sought a stable of road-tested, resilient musicians with whom to make his latest stand.

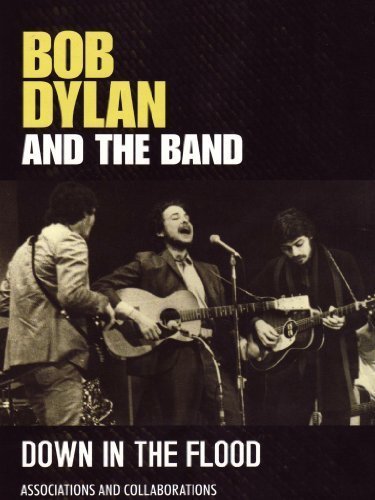

Down in The Flood – Associations and Collaborations chronicles the sporadic yet seminal working relationship between the Dylan and The Band, along the way examining the context and motives behind the music they wrote and performed together—from The Basement Tapes to The Last Waltz.

Appropriately enough it’s the original fusion of these figures on which the documentary most concentrates, when The Band were a Canadian-based outfit called The Hawks and Dylan was kick-starting his meteoric rise from folk hero to rock and roll renegade. Underscored throughout is a mutual respect that existed between the musicians, which for Dylan was not only tantamount to professional courtesy but to personal safety as well.

Unlike his contemporaries at the time in The Beatles and Rolling Stones, who as respective groups could isolate themselves from whatever pandemonium awaited their every move, Dylan was on his own. What’s more, contending with frenzied crowds was a heady-enough task for Dylan when they were on his side; confronting fiery, even hateful reactions after he’d “gone electric” was something far more dangerous and, it seems in retrospect, hurtful.

The man apparently still smarts from when he was condemned as “Judas” during a 1966 performance in Manchester, England. “Judas, the most hated name in human history!” Dylan groused to Rolling Stone contributing editor Mikal Gilmore in a recent interview. “If you think you’ve been called a bad name, try to work your way out from under that.”

The story told here of these most-pivotal years for both Dylan and The Band is compelling on its own, but added critical insights and observations—commentators include noted music scribes (particularly Barney Hoskyns, Anthony DeCurtis, and Robert Christgau) and musicians privy to the tale (rockabilly pioneer Ronnie Hawkins, who founded and mentored The Hawks before they ultimately became The Band; drummer Mickey Jones, who worked the kit on Dylan’s ’66 world tour)—give the circumstances explored here the weight they deserve. For fans of Bob Dylan, The Band, or even ‘60s and ‘70s pop music and culture in general, this film is certainly worth pledging your time.