Written by Lisa McKay

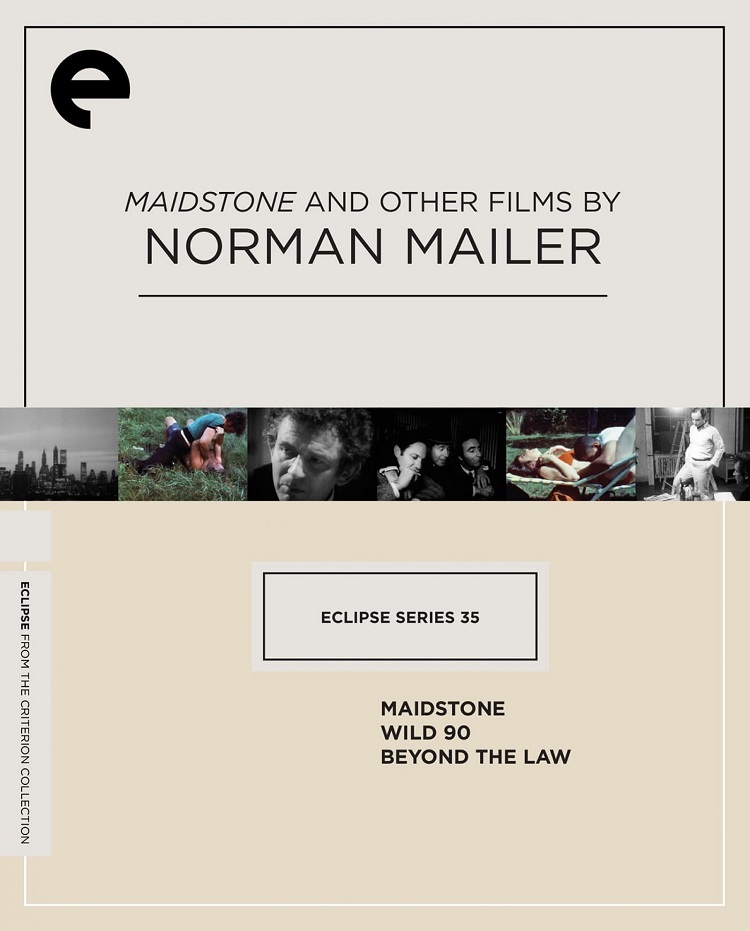

The fine film lovers at the Criterion Collection recently released a two-disk set containing the first three films made by American writer Norman Mailer. Wild 90 (1967), Beyond the Law (1968), and Maidstone (1970) comprise this collection released under Criterion’s budget-conscious Eclipse banner.

Norman Mailer’s reputation as a novelist was already secured by the time the cultural and political turbulence of the ‘60s rolled around, and he had been writing counter-cultural essays since the 1950s. An astute participant/observer of the era, he chronicled the times in a series of non-fiction books, one of which (The Armies of the Night) won a Pulitzer Prize. His outsized ego, characterized by a pugnacious, bullying machismo, made him one of the more memorable characters on the cultural scene, augmented by frequent television appearances and magazine interviews. His involvement in the public sphere and his fascination with the idea of celebrity likely explain his choice to expand his creative work into the realm of filmmaking. These three films, experimental in nature and inspired at least in part by the filmmaking exploits of artist Andy Warhol, could only have come out of the ‘60s. They disregard narrative form and technique (to their disadvantage) at a time when cultural, social, and artistic conventions were being regularly cast aside in favor of a freer form of expression.

Wild 90 is the first film Mailer made, and he served as director, producer, actor, and editor. The film is an exercise in ego run amok. Ostensibly about three gangsters (played by Mailer and two associates who show up again in this collection, Buzz Farbar and Mickey Knox) holed up in a ratty New York apartment, the film features improvised dialog (which is enough to make you realize the worth of even a mediocre screenwriter) and a soundtrack that is technically poor enough to make using the available subtitles a necessity. The cinematography is effective to the point that it makes you feel claustrophobic, much like the bad guys sharing close quarters. The production values are poor enough that the film in nearly unwatchable at times.

At its worst moments, Wild 90 feels as if three drunken frat boys found themselves in possession of some filmmaking equipment and suddenly fancied themselves auteurs. Mailer’s acting, peppered with odd, gutteral vocal tics, is awful. According to the essay included in the box set, Mailer, Knox, and Farbar essentially honed this gangster shtick in a bar in Greenwich Village and concluded that it was good enough to capture on film. That the filming itself was fueled by alcohol consumption does it no favors.

Beyond the Law followed a year later and, while still exceedingly rough around the edges, it’s a step up in quality from its predecessor. This film explores a theme that Mailer examined often in his written work, namely the ability of every human to be both sinner and saint, or cop and criminal. This time Mailer, Farbar, and Knox play vice cops, and the action switches between the precinct station, where the cops interact with a wide variety of criminals and suspects, and a restaurant, where Farbar and Knox are trying to impress a couple of blind dates (one of whom is played by an actress billed as Marcia Mason who is, in fact, the actress later to be known as Marsha Mason — not surprisingly, she’s the best thing in the film). Farbar’s character is improbably named Rocco Gibraltar, which has the effect of making him sound more like a porn star than a cop.

George Plimpton makes an appearance as the Mayor, and Rip Torn plays one of the suspects at the precinct. Mailer’s character, Francis X. Pope, speaks with a god-awful Irish brogue (which will make you appreciate the value of a dialog coach), and his acting is tinged with a smirking self-awareness that serves to pull the viewer out of the action. Flaws aside—the filmmaker’s efforts continue to be plagued by overall poor production values and some pretty bad non-professional acting)—Beyond the Law does provide some interesting moments in the precinct, and a good scene between Mailer’s character and his wife (played by Mailer’s wife at the time, Beverly Bentley).

Last, but certainly not least, we have 1970’s Maidstone, which is the most compelling and narratively cohesive of the three films (and I use the phrase “narratively cohesive” in the loosest sense). Shot in color and looking and sounding more like a professional production than the preceding films, Maidstone is a tale of political paranoia and … well, it’s hard to say what else it’s about. Mailer plays Norman T. Kingsley, a renowned filmmaker on the order of Bunuel and Fellini, who is inexplicably considering a run for the Presidency. The story, such as it is, involves various people seemingly vetting Kingsley for the candidacy while he’s in the process of making a movie on location in the Hamptons. The film gained a bit of notoriety for the closing scene in which Mailer and actor Rip Torn come to actual, blood-letting blows in a bit of surreal improvisation while the cameras continue to roll and Mailer’s wife and children scream in horror in the background.

Mailer’s approach to filmmaking eschewed preparation. His methodology apparently involved gathering a large number of friends, family members and associates together and giving them a theme to riff on—the dialog in all three films is mostly improvised, which sometimes works and sometimes is just painfully awkward. According to numerous reports, much alcohol was consumed during all three productions, which didn’t seem to help matters much. The real star in all three of these productions is Mailer’s own monumental ego, which is on full display. While these films can’t be considered essential viewing, they’re certainly a vivid representation of the workings of a certain intellectual fringe prevalent in the ‘60s. If you’re a student of the time period (or if you lived through it and don’t remember it very well) by all means watch them. If you’re a fan of Mailer’s (as I have been since high school), watch them and be grateful that his career as a filmmaker was short-lived and his career as a writer was a long and glorious one.

All three films are presented in their original 1.33:1 aspect ratio with original mono soundtracks. Wild 90 and Beyond the Law are both in black and white, while Maidstone is in color. There has been little effort made to clean these up—there are numerous scratches on the film as well as the occasional glitch or jump, and the soundtrack in Wild 90 is problematic to the point of being incomprehensible at times. The production quality improves chronologically, with many of these flaws being absent or greatly lessened by the time you get to Maidstone. Since this is an Eclipse release, there are no extras on the disks, but since this is still Criterion, neither will you go away uneducated—there are notes on the films by critic and curator Michael Chaiken, and they are well worth reading.