Spanish cartoonist Paco Roca returns with his most personal graphic novel to date, a nostalgia-soaked ode to the Franco-era Valencia of his mother’s youth. While he’s delved into his family dynamics before in The House, a look at how he and his siblings worked through settling their deceased father’s estate, his latest book digs directly into the family history of his mother. Antonia is the star of the book, as Roca turns his eye back to her formative years with her siblings in the 1940s.

Buy Return to Eden by Paco RocaAt this stage in his esteemed career, Roca is so confident in his immense talent that he starts the book with an audacious spread of numerous fully black pages, only gradually adding sparse white text that slowly coalesces into universal truths about the nothingness from which we all start, the brief flicker of our lives, and their insignificance in the grand scheme of things. It’s a startling reminder that Roca is the rarest of creators, equally as adept with the written word as the masterful artwork. As he sums up near the end of this sequence, “we wage a constant battle against oblivion, which seeks to erase the past,” with this book his stake in the ground to canonize for all time the history of his mother’s family.

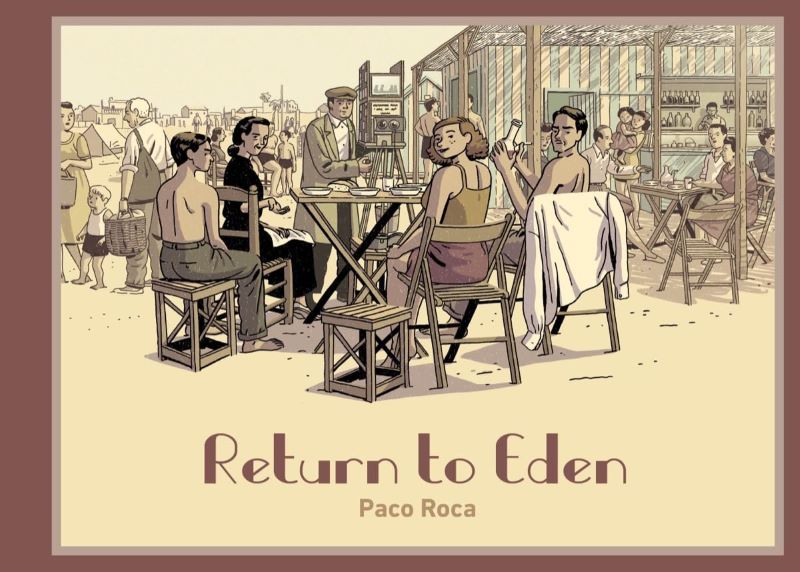

Utilizing an actual family photo (recreated from a reverse angle as his cover image), Roca recounts the personal history of all of his mother’s siblings and her parents. He also reveals the damaging legacy of Franco’s policies and the heavily patriarchal society that resulted in near-starvation poverty, total social ostracization of Antonia’s sister who became pregnant out of wedlock, and limited education for Antonia. She never learned to write, and only learned to read in secret late in adolescence in order to understand her disowned sister’s letters. It’s heartbreaking to wade through the soul-crushing lack of opportunity available to Antonia, especially because it’s all true.

The photo takes on immense significance to Antonia as she progresses through life, as photos were extremely rare in her youth and it is her only physical record of her favorite family members. Not included: her stoic and physically abusive father (Roca’s grandfather), as well as her oldest sister, so much older they were never close. The photo takes on added weight when Roca shifts the timeline to the present, as Antonia moves to a senior-living facility and despairs when it goes missing. At this point, the book recalls Roca’s most famous work, Wrinkles, as the elder Antonia grapples with the sunset of her life, her fading memory, and her temporary parting from the only physical item still retaining any meaning to her.

Roca is nearing old age himself now, like me, making his interest in looking back all the more understandable and relatable as we recognize that there’s more life behind us than in front. He’s examined the past and the damage of Franco’s reign before in The Winter of the Cartoonist, a true story of five editorial cartoonists who fought for creative freedom in the 1950s, but his personal connection to Antonia’s tale gives it added weight as we realize how tenuous his mere existence is after the hardships of her youth. When one considers that his nearly illiterate mother gifted the world with this superbly talented writer and artist, one must also wonder at the incredibly unlikely odds resulting in the miracle of the existence of this book and its creator.