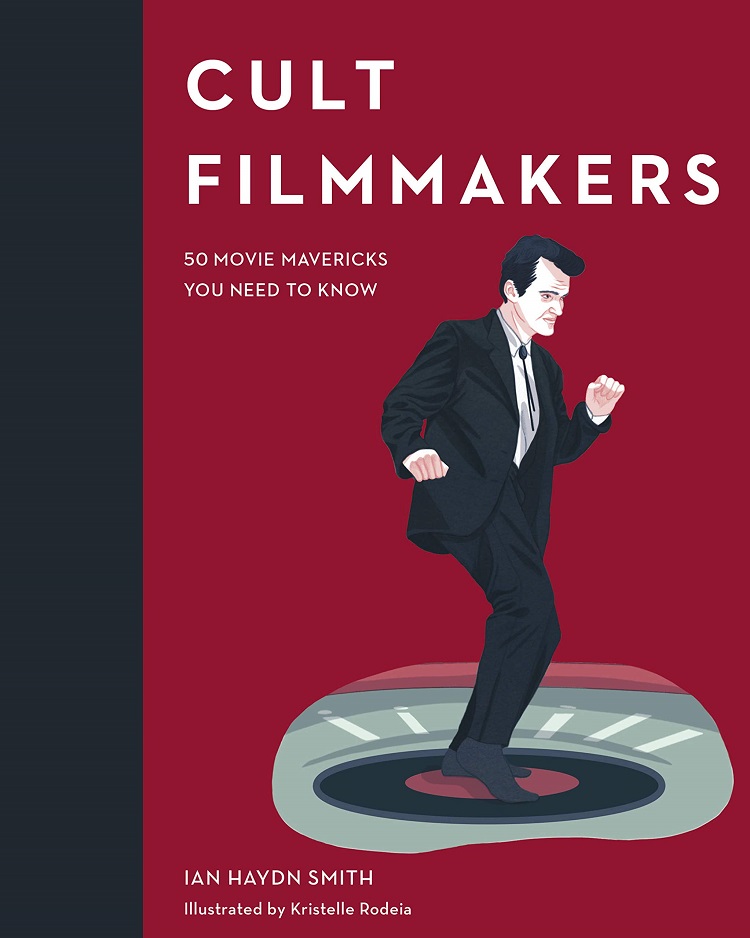

Cult Filmmakers finds author Ian Haydn Smith shining the spotlight on 50 movie mavericks. The illustration on the cover by Kristelle Rodeia, who provides all the drawings of directors that accompany Smith’s essays, is a dancing Quentin Tarantino dressed as Vincent Vega from Pulp Fiction, revealing that Mr. Smith’s definition of “cult” might not be what everyone expects. In his Introduction, he explains that “rather than offering an authoritative guide through a rich history of cult filmmaking, this book aims to be another voice in the conversation about cult cinema.”

The book focuses on 39 men and 11 women, over a quarter of the directors are from outside the United States. The earliest entrant is “black cinema pioneer” Oscar Micheaux, who got his start setting up a production company to adapt his novel when the black-owned Lincoln Motion Picture Company wouldn’t give him creative control. Smith indicates that the book was Micheaux’s autobiographical novel The Conquest: The Story of a Negro Pioneer, but other online sources such as The New York Times, Encyclopaedia Britannica, and the NAACP state it was based on The Homesteader, the same name as the film (1919). Ana Lily Amirpour is the director with the latest feature-film debut to make the cut, A Girl Walks Home at Night (2014), and is also the first listed because the filmmakers appear in alphabetical order.

The midnight-movie circuit helped demonstrate the appeal of alternative cinema as it allowed artists and audiences with offbeat tastes to connect. The concept became a cultural phenomenon in the ’70s and while many movies found great success during the witching hour, the four major titles were (listed chronologically) Alejandro Jodorowsky’s El Topo, John Waters’s Pink Flamingos, Jim Sharman’s The Rocky Horror Picture Show, and David Lynch’s Eraserhead. All but Sharman are featured. Speaking of witches, Smith writes about a number of horror directors, including John Carpenter, David Cronenberg, and George Romero.

Smith’s does not limit himself to filmmakers whose work has only appealed to a cult following, such as Kenneth Anger and Lizzie Borden. When directors have been embraced by the industry, such as those who cast wildly popular movie stars or have been awarded Oscars, such as Darren Aronofsky and Kathryn Bigelow, it takes a moment to remember their appeal used to be limited. It’s hard to remember a time Tim Burton, whose work appears on licensed products at every Hot Topic store across America, wasn’t accepted by the mainstream, but Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure and Beetlejuice were modest successes before his take on Batman.

The book concludes with “Key Works,” a list of essential films by the directors covered. As a Gen-X cinephile growing up near Los Angeles in the ’80s and ’90s, I had an advantage over my fellow Americans in smaller states and cities when it came to seeing cult films thanks to theaters devoted to independent films, like Jim Jaramusch made; foreign films, like Jean-Pierre Jeunet made; and revival houses that screened what Roger Corman made. Nowadays, with all the content available on cable and streaming channels as well as what’s available on the Internet through various means, cult-film fans will have a much easier time watching the “Key Works,” which readers will be eager to seek out because Smith’s essays make a compelling case for all 50 filmmakers.