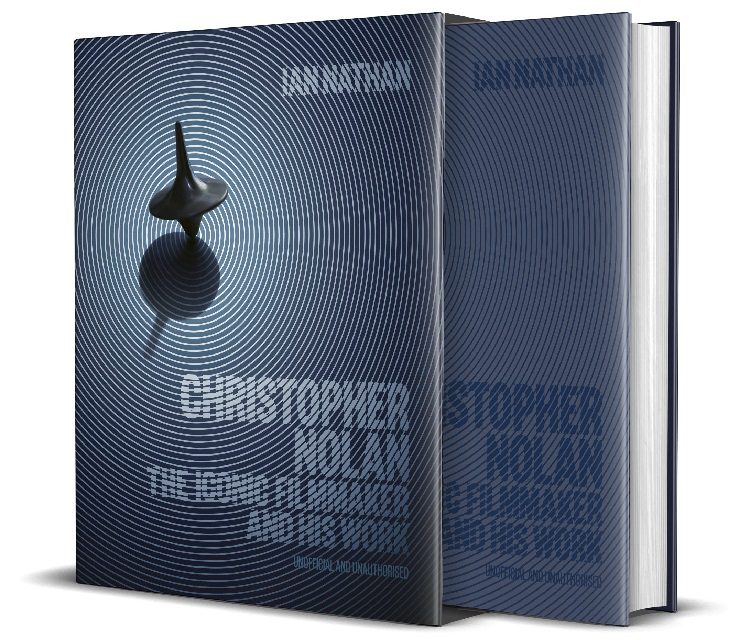

Housed in a slipcase, Ian Nathan’s Christopher Nolan: The Iconic Filmmaker and His Work takes readers on an unofficial and unauthorized tour through the director’s filmography. Covering 12 films released over 23 years, as well as a preview of Oppenheimer, Nathan explores how, as stated in his Introduction, “Nolan has done the impossible – pursued a personal, idiosyncratic, often brilliant, and consistent style within the studio.”

Starting with Nolan’s days as a 19-year-old student at University College London where he co-founded the UCL Film and Television Society along with “fellow student and girlfriend, later wife and producer” Emma Thompson, the reader sees his drive to become a filmmaker even though he never formally studied in school. Yet, he and his fellow Society members came together to “shoot one day a week and kept that up for most of a year,” Nolan told AV Club, and for a few thousand pounds made his feature-film debut with Following (1998), a modern noir thriller that finds Nolan already using a non-linear narrative.

Nolan worked his way to the top of the industry with a breakout indie hit (Memento), a remake (Insomnia), and a reboot (Batman Begins) that helped paved the way for Hollywood’s Superhero Era, especially after its widely acclaimed sequel (The Dark Knight) was both a critical and box-office success, winning industry awards and earning over $1B. In an age where the studios became more interested in IP and the potential ancillary sales from their movies, Nolan went onto become a brand by creating original science fiction (Inception) and historical (Dunkirk) epics. He’s one of the few writer-directors whose name alone draws people to theaters as each new film becomes an events, which is one reason he is frequently compared to Stanley Kubrick.

At the outset, Nathan stated his goal was to “contextualize Nolan’s worlds – the inspirations, the ambitions, the ever-more challenging shoots, and the success – and also go some way to getting to the secret heart of his stories.” Thankfully, the book is not a stuffy, literary read as some film studies can be. Nathan’s writing style is engaging, more novelistic than journalistic, as seen at the outset as his details about the UCL’s Bloomsbury Theatre aren’t necessary to Nolan’s story but are welcomed as they help the reader visualize the scene and elicit trust in the guide for this impending journey.

Nathan serves as a literary archeologist, excavating Nolan’s films, digging into their production, their themes, and the reactions they earned. He also offers his own assessments, such as claiming that The Dark Knight Rises was unfairly considered “a lesser film than its predecessors,” which was an accurate claim in this reviewer’s eyes. Christopher Nolan: The Iconic Filmmaker and His Work is well researched and highly recommended for Nolan aficionados.