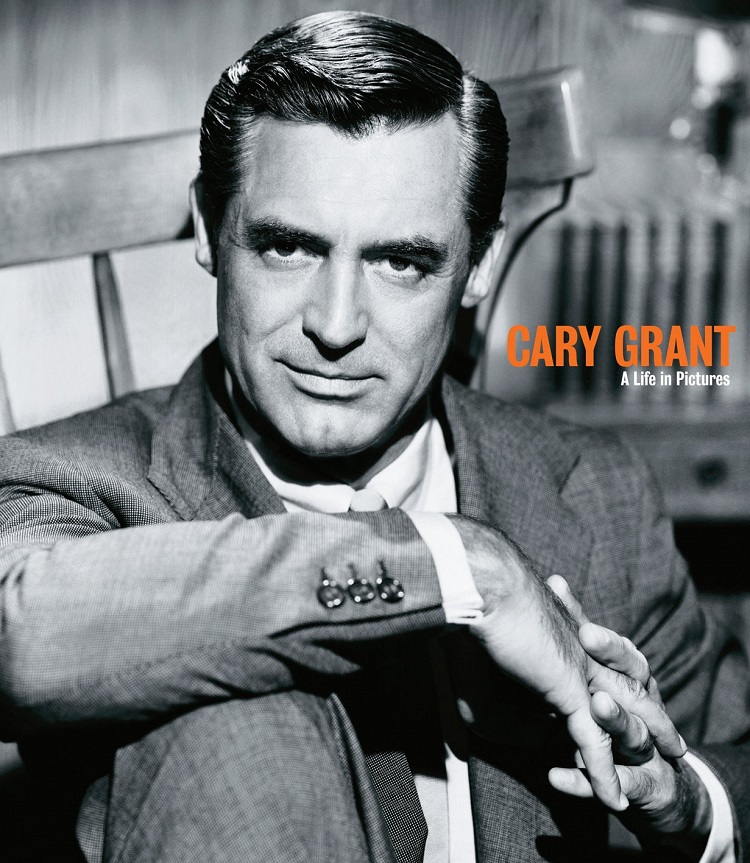

Whether you’re a classic film fan or not, you’ve probably heard of Cary Grant. Like Marilyn Monroe, James Dean, or Humphrey Bogart, Grant is one of those actors whose status as an icon transcends the movies. His persona as the unflappable, impeccably dressed leading man is ingrained in our culture, thanks to films like Alfred Hitchcock’s To Catch a Thief (1955) and North By Northwest (1959). And now, with the handsome new large-format hardcover Cary Grant: A Life in Pictures, you too can learn that a persona is often just that.

The son of a hard-drinking suit presser, Archibald Alexander Leach was born on January 18, 1904 in the working-class city of Bristol, in southwestern England. At age 9, Archie’s mother disappeared, and he believed her to be dead. In fact, Elsie Leach had been committed to a psychiatric hospital – a fact that her son would not learn until he had already become “Cary Grant” two decades later. Throughout his entire life, the former Archie Leach never denied that “Cary Grant” was a character he played, and one that he had as hard a time living up to as other men.

“I think most of us become actors because we want affection, love and applause,” Grant says, in one of the many quotes that serve as chapter marks in this beautifully art-directed volume. And as with all Hollywood myths, the truths of Grant’s life were rarely as effortless. He left school at 14, joined an acrobatic ensemble, and spent the next two years as a trapeze artist. He eventually followed the troupe to New York City in 1920, where he performed on the stage of the legendary Hippodrome 456 times. When the revue returned to the U.K., Leach stayed and began doing odd jobs to stay alive.

Soon after, he met wealthy theatrical producer Jean Dalrymple, whose work with George Balanchine led to the creation of the New York City Ballet. Dalrymple (as Frederic Brun writes in the excellent biography that opens the book) “made him give up his taste for stilt-walking and the circus,” and taught him, in effect, how to be Cary Grant. Soon after, Leach became a working actor, landing parts in burlesque comedies and musicals on Broadway and eventually a contact with Paramount Pictures. Paramount suggested he adopt the stage name Cary Lockwood, but Leach instead chose Cary Grant.

“Archie loved the initials C and G, which stood for Clark Gable and Gary Cooper; two of the biggest stars of the period. They became his good-luck charm,” Brun writes.

Cinema success came quickly, thanks to roles opposite Marlene Dietrich in Blonde Venus (1932) and Mae West in She Done Him Wrong (1933). The Cary Grant of those early films often appears callow and inconsequential, less impressive perhaps than the sharp suit in which he is nattily attired. That all changed when Grant was loaned out to RKO Radio Pictures. Beginning with the supernaturally screwball Topper (1937) and continuing with the charming romantic comedies Bringing Up Baby (1938) and Holiday (1938), we begin to see the persona that we associate with Grant and would for the rest of his life. With His Girl Friday (1940) and The Philadelphia Story (1940), the dye was cast.

Grant would continue as a leading man for another quarter century, until his retirement from motion pictures, following Walk Don’t Run (1966). But the apparent effortlessness of his screen success during his film heyday was belied by romantic dramas and failed marriages.

After a brief betrothal to actress Virgina Cherrill in 1934-35, Grant remained single until he met Barbara Hutton, then the richest women in the world. They married in 1942 and Grant discovered “high society, incessant travel and the comfort of a life of luxury.” They divorced three years later and, despite the general perception that Grant had married her for her money, Hutton didn’t give him a cent.

Grant married actress Betsy Drake in 1949, a union that would last until 1962. During the 13 years of marriage, Brun writes, Drake “busied herself with all aspects of her husband – from his sexual uncertainties to his depressive state.” Brun then goes on to talk at length about the actor’s experimentation with LSD, but never addresses the reference to “sexual uncertainties” (at least not in the biography text), which feels like a gigantic missed opportunity. It’s a known fact that Grant and actor Randolph Scott shared a beach house in the 1930s, after meeting on the set of Saturday (1932). What’s not known, and likely never will be, is exactly what went on there. Editor Yann-Brice Dherbier devotes an entire section of the book to beefcake photos of Grant and Scott together, with captions about “rumours.” But the salaciousness feels out of place. It’s hard to be fawning and engage in suggested character assassination in the same piece of work but, on this issue, the book seems to want to have its cake and eat it too. Cary Grant maintained that he was straight until the day he died. I wouldn’t mind at all if he wasn’t, but I chose to take his word for it.

Grant’s mid-1960s marriage to actress Dyan Cannon – more than thirty years his junior – was brief and tumultuous, but yielded a daughter, Jennifer, who became the light of her 62-year-old father’s life. Sadly, the post-divorce custody battle stretched on for more than a decade, complicated by accusations of violence and what Brun refers to as an “alleged sexual double life.” The question of orientation is further clouded by Grant’s love affair with Italian beauty Sophia Loren, which began on the set of The Pride and the Passion (1957) and reemerged (at least on Grant’s part) during the making of Houseboat (1958), where Brun describes a “besotted” Grant as pursuing Loren, despite her protestations.

Can you imagine – a woman saying no to Cary Grant? I could introduce you to dozens of female classic film fans on the internet who would find that absurd. But isn’t that the point? Cary Grant was both a troubled man and a manufactured myth and, for the most part, Cary Grant: A Life in Pictures does an effective job of telling both stories. For me, I choose to focus on the myth.

“All men would like to be Cary Grant,” a journalist is quoted as saying to the actor on the book’s back cover.

“Including me,” Grant replied.