Written by S. Edward Sousa

Best known for provocative films such as Shock Corridor, The Crimson Kimono, or The Big Red One, Samuel Fuller spent his life making inescapable art. He was a filmmaker’s filmmaker and a writer’s writer, whom director Wim Wenders—Paris, Texas among others—once called “one of the great movie directors of the 20th century, most certainly its greatest storyteller.” Fuller had spunk and punch, and very little of what drags most artists to the ground, excess. His ideas were straightforward and to the point. Take for example his most controversial work White Dog, the tale of a virulent racist German Sheppard and his black trainer. The tale is an allegory of race in America, of whether people can change or hate is born buried inside them. The film couldn’t find a home in America for close to twenty years, because Fuller knows no other way than being straightforward.

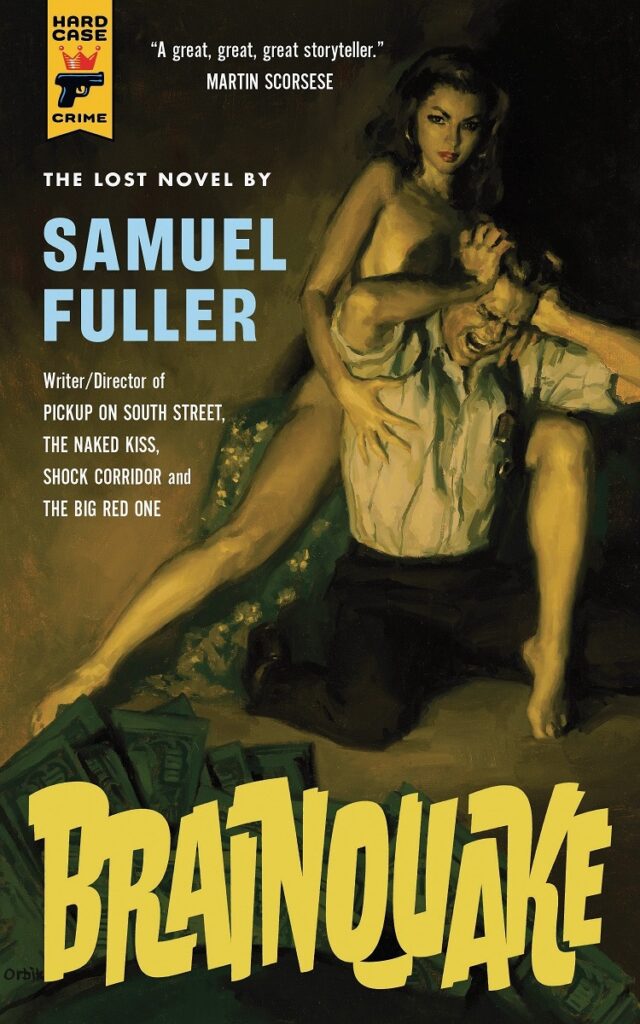

And you see it here in Brainquake, Fuller’s last, and “lost,” novel. Published in both French and Japanese just before Fuller’s death in the mid-1990s, while Fuller was living in self-imposed exile in France, the novel is only now being printed—by the fine folks at Hard Case Crime—in English, and in Fuller’s homeland, the U.S. It’s a shame too because Fuller’s frank dissection of life comes through in the curt sentence structure and direct language of this novel.

The story centers on Paul Page, a man born with a peculiar condition—debilitating headaches morph into haunting hallucinations turning Page into a physically violent and turbulent individual. Knowing he could never live a normal life, Page’s father set him up as a bagman for the New York mob dropping unmarked cases of cash for unknown recipients around the city. It’s a quiet life and Page seems the perfect candidate, the silent loner type he spends his time fantasizing about a woman he refers to as Pale Face—a firm beauty and single mother he leaves doorstep flowers and poetry for.

The book opens with Page on a park bench watching Pale Face stroll along with her baby and some unidentified man. When the baby yanks on one of its toys a shot rings out, killing the man and setting of a small string of violence in the park. It’s a twist only Fuller could pull off, murdering babies. As the classic noir tale unfolds readers are introduced to a slew of near predictable characters. There’s Paul’s bagman mentor, Hoppie the degenerate with a heart of gold. There’s Father Flanagan, the priest who doles out penance through crucifixion. There are modern-day pirates whose sights are set on the bounty of crooked bagmen. And there’s Helen Zara, a third-generation NYPD detective who seems to embody the crime novel’s moral center—she’s on the right side of the law, but she’s covered in grit. Zara is a twist of a character for Fuller, whose detractors often cast him as a misogynist and a racist. Here, in the wake of White Dog, Fuller gives personality to not only Zara, but a host of women defined by their capabilities and emotional depth rather than their relationships to men.

As the story unfolds Page breaks rank to connect with his fantasy while his boss—referred to as “The Boss” in true noir fashion—struggles through her own existential crisis. She’s confined to her life of crime so she can afford the specialized treatment her adopted mute daughter requires. She’s paralleled by Paul who in his attempt to protect and pursue Pale Face is drawn in to protecting her. The criminal’s struggle is a present theme throughout Fuller’s work—from The Naked Kiss to The Dark Page—there is the world of truth and honesty and the world of insatiable appetites, deviancy be damned. Even in Fuller’s The Big Red One (both the film and the novel), the characters exist between a state of duty and savagery.

Brainquake embodies this essence of Fuller whose philosophical underpinnings appear to be driven by both personal fascination and the desire to agitate. This disposition arguably made Fuller one of the 20th century’s great art-punks. His form was stripped down and to the point, and Brainquake’s lyrical pointedness embodies the exposition of ugly truths lurking in American punk. Late in the novel, in the midst of a mercy killing Page is hit with a ‘brainquake.’ Fuller writes:

The brainquake came without warning. The flute shrieked. In brighter reddish-pink Eddie was smashing the baby against the wall….Paul clicked the safety off and fired point blank and the room shook and spun and pictures fell from the walls and brain cells were pulling the baby into the crevice.

Psychedelic barbarities abound, Fuller’s candid language is hardly far removed from Memphis punkers Ex-Cult’s “Flickering Eyes,” whose three-line refrain reads: Dead on the front page, victim of the heatwave, I saw your flickering eyes.

A brutal threat lies beneath. And it’s the beauty of both Brainquake and Fuller as an artist—the ugly, savage, lingering fear which keeps Brainquake teetering and readers salivating for more. It isn’t the work that will define him, but it is a reminder of who Fuller was, a menace, a creep on Broadway, a delinquent on Main St. He is the constant churning of the American psyche wrapped in fever dreams of sex and crime, race and violence, and a fickle humanity. In his fifty-plus years as an artist he embodied what can only be described as American Nihilism—the faithless ideology of crooks and critics, who see no allegiance and know no trust beyond their own ambition, whose only mode of expression are coerce comments spewed from the peanut gallery with vicious clarity.

Yes, Samuel Fuller was the last of a dying breed, born in the pre-war dawn of class based con-men and seminal suckers, raised on the cheap arts of dime-store novels and double features, and matured in the trenches The Great War, Fuller learned to bleed in the most straightforward of manners, all over the page.