There’s a funny thing about favorite movies. You can easily find people to share a love for anything Harry Potter or Lord of the Rings or Star Wars. You can go a little further and find friends who enjoy 2001, On The Waterfront, or The Philadelphia Story. Then there’s another level where you might mention a movie you love that not everyone has heard of but mostly they are aware of like Eraserhead, Freaks, or 8 1/2. Those are part of the popular-culture vernacular and you don’t get weird looks when bringing them up in discussion. Then there’s that final level of favorite films – the ones where you bring them up in mixed company, and even among film fans, you get weird reactions and start to doubt their actual existence. For me, that was The Navigator: A Medieval Odyssey.

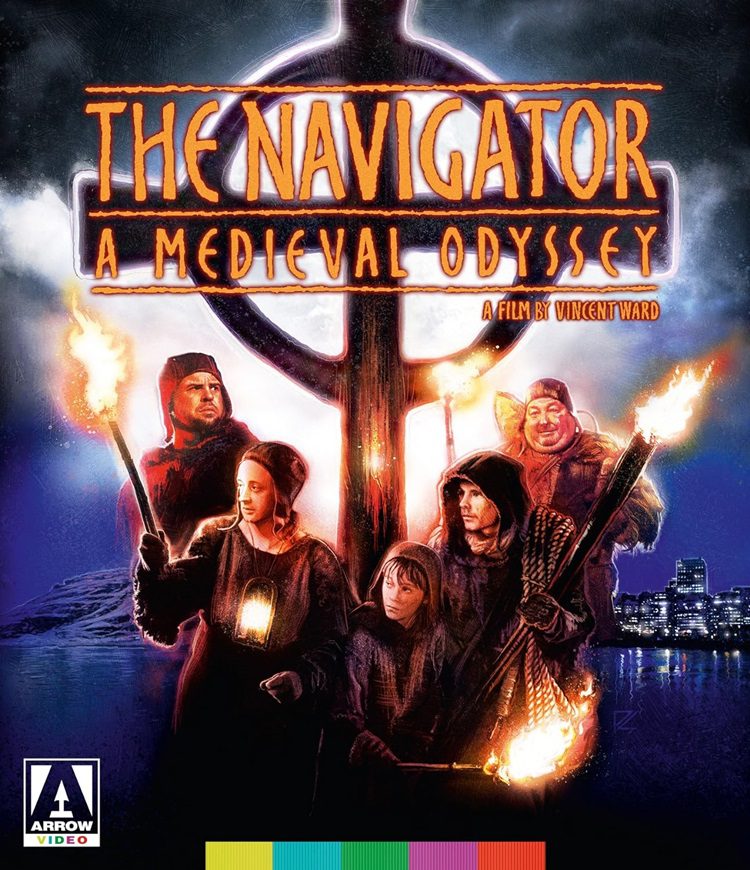

In early 1989, I went to a small art theater on the Balboa Peninsula to see a little film from New Zealand that had an interesting blurb. I was completely enthralled by the film and before I was able to see it a second time, it was gone from the theater and disappeared from normal film talk about science fiction and foreign films. Luckily, I had bought the soundtrack so I had proof that it existed. But for years, I was met with blank stares when talking about the film. Just describing the concept of the film inspired others to try to track down the film but other than long out-of-print VHS versions you might find at small locally owned video stores, it wasn’t curated anywhere else. Until this Blu-ray release from Arrow Video.

The Navigator: A Medieval Odyssey starts in a stark black and white Cumbrian city besieged by the Plague in 1348. This isn’t the normal setting for what is a science-fiction film at its heart. This is a bleak New Zealand countryside that’s more Norse looking than Kiwi. The artful combination of music and visual effects is much more reminiscent of The Seventh Seal. These scenes show the impossible visions of young (maybe 9-11?) Griffin. He convinces the village that he has seen how to prevent the Black Plague from decimating their village. They are to dig a hole through to the other side of the planet and place a cross at the top of a cathedral in “God’s City”. This starts the journey that would fit somewhere between Tolkien and Chaucer. The group is composed of older brother Connor, angry Arno, merry Martin, innocent Ulf, and skeptic Searle.

The group digs through the Earth and ends up in current-day (1988) Auckland, New Zealand in color. A majority of the rest of the film is the group taking their classical journey of the hero to get a copper crucifix created and then finding the cathedral and getting the cross to the top of the church. The journey has the usual time travel “fish out of water” humor as they try to figure out about crossing highways, cars, trains, and even submarines. They are led by Griffin’s visions that solve the puzzle at each step of the way. The problem is that Griffin had a vision that a member of the group dies in the process of saving the village. This propels the story to its surprising conclusion back in 1348 Cumbria.

The film pulls from all the usual quest and time-travel sources. There are references drawn from Lord of the Rings and plenty of allusions to the journey of Odysseus. The group encounters what they think are giants and monsters. Their reactions to unknown technology is a trope going back to The Time Machine and repeated across multiple novels and movies. They move forward thinking that this other side of the flat Earth is “God’s City”. If the Earth is flat – their side is the evil side and this is the good side. This is an equivalent of Heaven and so they don’t just question all of the “magic” they see. There is humor – like the group crossing the highway like a group fording a huge rushing rapids but it isn’t played as a comedy as in The Visitors (1993) where the time travel from Medieval times to modern Europe is mostly for humor.

Viewing the film again after all these years, I’m struck by how on point my memory of the film has been. It’s a beautiful film that plays well as “art film” and as more traditional “science fiction.” The plot worked as a symbolic link in 1988 between the Plague and AIDS (as referenced in a scene with multiple television screens in the film). Today, it plays more interestingly as the journey – as a way to link the past to the present. I hope that there’s still an audience willing to take a chance on a film they’ve never heard of and maybe let it become their new favorite film to help others discover. It’s a fun and rewarding quest.

Arrow Video has put together a great package. The film looks and sounds even better than I saw it in that small theater in California. There is a booklet worthy of a Criterion Collection release, an audio essay, a documentary on the director Vincent Ward (attached to direct Alien 3 after Walter Hill saw this film) and the trailer.

Arrow has also released Vigil – the first film from director Vincent Ward released in 1984.

Vigil shows much of the talent and promise that would be delivered in The Navigator. The story of Toss who lives on a sheep farm. Her father dies just as a mysterious stranger arrives and starts a relationship with her mother. The film plays out much more symbolically – the characters are more archetypes – “Daughter,” “Grandfather,” “Mother,” and “Stranger.” The film is also beautifully shot and plays out more like a mid-’80s European film directed by Holland, Kieslowski, or Herzog.

The Blu-ray is also loaded with audio essay, a documentary from the set, a documentary on Vincent Ward, and trailer. I’m impressed with the quality work that Arrow Video is doing with these releases.