At 97 minutes, An American Werewolf in London (1981) is a good short horror film that should have been shorter.

It feels unfinished. It doesn’t hang together as neatly as it should. For this reason, I’ve always admired what the movie almost achieves, rather than what it ends up as. The movie earns a ton of good will, but it’s a soft miss.

I love the opening sequence. Two American college boys, David (David Naughton) and Jack (Griffin Dunne), backpack across the English moors. From the deliberate buildup of their jaunt to a small town, to the chilly greeting they receive at a pub (The Slaughtered Lamb), to the attack of a werewolf: it’s a wonderful short. We grow to like the boys, and the writer-director, John Landis, layers in some lovely, creepy atmospherics.

Thus follows a long midsection. Recovering in a London hospital, David is drawn to Alex (Jenny Agutter), the attractive nurse who tends to him while he suffers from absurd, macabre dreams. Visited by a dead, mauled Jack, who only David can see and who warns him about the curse on him and the misery and pain he’ll cause, David slowly comes to grips with survivor’s guilt. And as his descent into lycanthropy nears, the head doctor, Dr. Hirsch (John Woodvine), investigates to learn the true nature of his condition.

We move, then, to the werewolf transformation scene, a classic of its kind, with Oscar-winning makeup and visual effects by Rick Baker. It’s an astounding bit of artistry, and it comes as the movie slows to a crawl. Like David, the viewer senses that something needs to happen, to crank things forward. For all its novelty at the time, the transfo scene is just that—a naked opportunity to set then-state-of-the-art effects to an ironic rock music soundtrack. If nothing else, this is emblematic of Landis’s larger scheme, to modernize the werewolf movie of yore.

In the run-up to the climax, a more decomposed Jack summons David to a porno theater after David’s hairy and murderous night on the town. Joined now with the talking cadavers of David’s victims, Jack issues one final grave warning about the tragedy that will continue to build if David doesn’t kill himself. It’s a funny bit—not hilarious, but quirky. This, and all the best parts of Werewolf (e.g., the sustained suspense and self-knowing smirk of the opening minutes, the brief, sharp shocks of violence, the chase in the Tube, Dunne’s performance and character, Baker’s effects), helped jolt the werewolf subgenre back to life. The film retains a dark charm. While I’m inclined to carp about the end, it is affecting in its abrupt way (thanks mostly to Agutter). It shouldn’t be, though. Weakened by lazy dialogue and shallow characterization, the tragic romance between David and Alex is undercooked.

This is the sad truth of An American Werewolf in London. The things it does well are so effective that I keep rooting for it to be a more satisfying film each time I see it. The clarity of the Arrow reissue is stunning, and I have endless enthusiasm for Robert Paynter’s cinematography. Aside, though, from the movie’s finer attributes, we’re not left with much of a story. Two dudes go to Europe, a werewolf attacks them, one lives and recovers under the watchful gaze of a nurse with whom he falls in love, and (despite the wry warnings of his dead friend) he’s only given final release when in true fang under a full moon. It’s a simple series of events, but the film doesn’t have the dramatic goods to transcend the greatness of its stylistic ingredients.

I suppose Landis’s fusion, so-called, of horror and comedy should intrigue; is what should help the movie rise above its trad roots. It’s not over-reliant on special effects, and it sports a winning modesty. Furthermore, the dry humor never outstrips the movie’s dominant flavor. Werewolf remains a horror film with a grim conclusion. (It’s common for people to note the similarities the movie shares with Joe Dante’s The Howling, the other good-to-great lycanthrope film of that same year. I’ll just say the Dante is the better story.) In terms of execution, though, Landis doesn’t give the characters much substance. The banter between them is bubbly, but in a flat sort of way. And the comedic tone is more sophomoric than clever (and kind of lame). Still, next to the longform music video for Michael Jackson’s “Thriller,” Werewolf is my favorite Landis film. All it needs are richer characters and a stronger story.

Overall, An American Werewolf in London would have made an excellent two-reeler. (Since I’m in a cranky mood, I’ll just come out and say that Landis’s record of accomplishment as a feature film director is spotty. As amusing as The Kentucky Fried Movie, Animal House, and The Blues Brothers are, they all share a sewn-at-the-seams quality, as though he’s limited to smashing together a bunch of cool set-pieces that rarely coalesce.) As a feature film, it misses the mark. It leaves you wanting more. Much more.

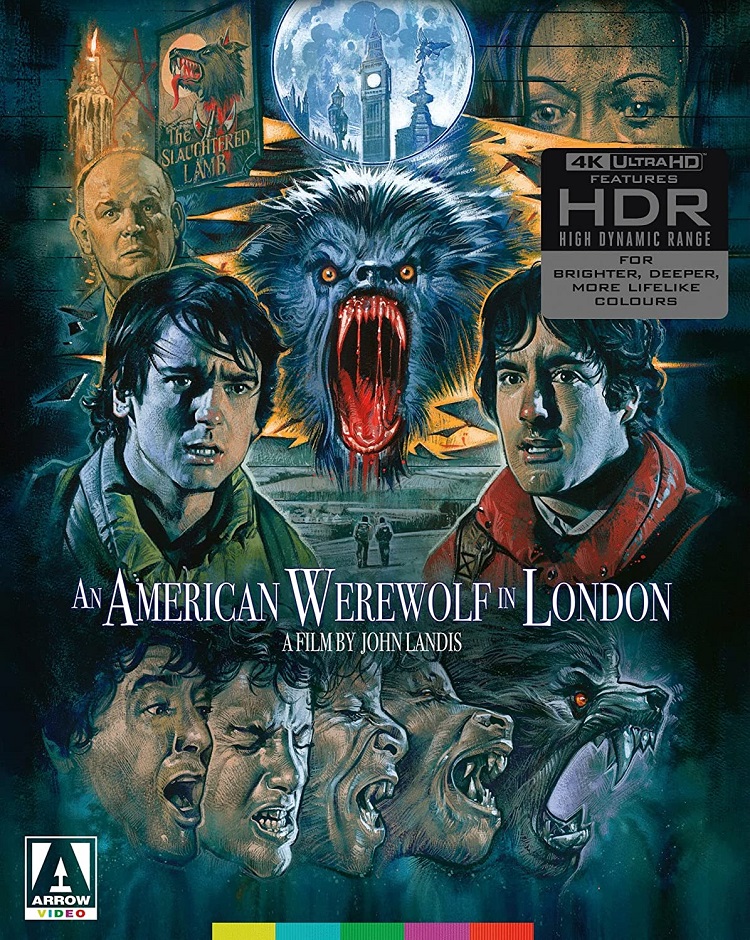

With reproductions of lobby cards and a booklet that celebrates the movie (replete with original reviews and new essays), the limited-edition Arrow 4K UHD is the latest in a line of beautiful Arrow releases. The plenitude of extras is staggering. You have a double-sided foldout poster. You also get audio commentaries with Naughton and Dunne and filmmaker Paul Davis. But wait, there’s more: two feature-length documentaries, a new-ish one on the Universal Studios werewolf films and an older look back at the Landis film. A slew of interviews with Landis are available, as are conversations with Baker and behind-the-scenes footage of Baker’s workshop. A collection of silent outtakes, a storyboards feature, and a stuffed-to-the-gills image gallery also add to the glut of delights.