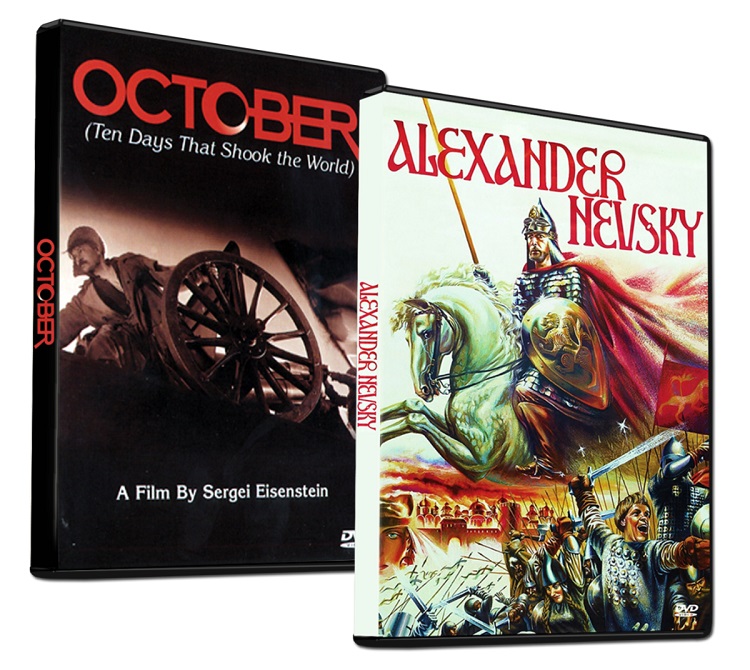

Sergei Eisenstein was one of the most important film theorists and directors of early cinema. If he didn’t invent the montage, then he certainly perfected it, making it more than just a series of images put together to tell a literal story. He believed, and proved with his films, that the right images juxtapositioned against each other could tell a symbolic story and elicit an emotional response. His Battleship Potemkin (1925) is considered one of the greatest and influential films of all time. Corinth Films is about to release two other lesser-known films by Eisenstein, the historical epics Alexander Nevsky (1938) and October (Ten Days that Shook the World) (1928). Both are being released on bare-bones DVDs.

It is impossible to remove the films of Eisenstein from the place and time in which they were made. To say that he lived and worked in a tumultuous period in Russia’s history would be a great understatement. He lived through the Russian Revolution, World War I, and World War II. His country went from being an imperialist nation ruled by Czars to the first communist country in the world. All of this greatly influenced Eisenstein’s filmmaking from the way he thought about life and art to the topics he made films about to the ways in which his films were censored by the growing communist regimes.

October (Ten Days that Shook the World) deals directly with the Russian Revolution while Alexander Nevsky tells the story of a great Russian leader from centuries before Eisenstein’s time. Yet it too has something to say about the times in which he lived as we’ll soon see.

Alexander Nevsky was a historical prince who ruled over a large swath of what is now Russia at a time when invaders seemed to be coming from every angle. The film depicts an invasion from the Teutonic Knights on crusade and Nevsky’s heroic defense of his homeland. It worked as an effective propaganda piece designed to persuade modern Russians to defend their homeland against the likely invasion by the Nazis.

The plot is incredibly simple. The Teutonic Knights have sacked the city of Pskov and are set to conquer the rest of Novgorod. Alexander Nevsky (Nikolay Cherkasov) rallies the common people to war where they win a decisive battle on ice which leads them to ultimate victory. The majority of the characters are as nameless as they are faceless. There is some attempt to make it personal with a bit of silliness over two men waging contest over who is the bravest and thus will when the hand of a fair maiden, and of a strong female warrior proving her own heroics, but mostly it’s a lot of bodies flailing against one another.

But Eisenstein is really good at throwing flailing bodies around. In long shots, he lines the soldiers up in geometric patterns then has them run towards each other in visually fascinating ways. In one scene, one group of soldiers lock their shields together then as the enemy charges towards them they drop their spears stabbing them in unison. Then another group runs towards them only to meet the same end. Then again and again. Eisenstein seems to love patterns, as he lines soldiers up in particular ways then runs the action multiple times as if on a loop.

He’ll move to a close-up of one soldier as we watch him slash and stab towards the camera while in the background untamed masses fight in an endless mess. Over and over again, the film finds interesting ways to demonstrate the awesome ferociousness of this war. It is a visually stunning masterpiece.

It can be overwhelming at times, and exhausting. This is especially true since the film has little interest in the actual narrative. We’re given very little information about who Alexander Nevsky was, or what he is fighting for. We’re given even less about his countrymen. As someone standing well outside this history, I found myself completely uninterested in the battle’s outcome. This isn’t a film meant for me or you. I doubt Eisenstein knew it would be shown much outside of Russia and certainly not nearly 100 years after it was made. Presumably, his contemporaries were well versed in Russian history and one assume Nevsky was something of a cultural hero, and thus the details of his life were not necessary. It would be like making a film on the American Revolution today. I wouldn’t need a long back story on who George Washington was nor why he was fighting against Britain.

The backdrop to the making of the film is the rise of Nazi Germany. Hitler had raised a great army and was posing himself to take over the world. Russia stood at his border unready for war. But the political powers could see war was coming regardless. In that way, Alexander Nevsky is pure propaganda. It is a reminder to the Russian people that they had stood up against great foes before and won. Now was the time to do it again.

Eisenstein is credited as both co-writer and co-director. My understanding of this is that the powers that be did not want him to stray into what they called formalism. That is to say that officially they did not want him to make his film too arty or intellectual so as to be confusing to the untrained masses, but in reality, they needed to keep him in line. His films needed to conform to the official doctrine.

October (Ten Days That Shook the World) was similarly a propaganda piece. In fact, my review of the film could almost be completely copied and pasted from my thoughts on Alexander Nevsky – it is a brilliantly shot piece of cinema with some incredible visuals, but a bit muddled narratively speaking.

Filmed ten years after and in celebration of the October 1917 Russian Revolution, the film is a simple retelling of those events. In 1905, the peasant classes revolted against the Russian Empire. The Czar promised reforms but they were slow to come. In February 1917 again, the people revolted and a provisional more parliamentary-style government was formed. But the representatives were all from the upper classes and they did little to help the peasantry. In November, the Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, seized the government and created the Soviet Union we know today.

The film covers all of this and more at a breakneck pace. It is a silent film and so there is very limited dialogue, even less so than most silent films I have seen. Intertitles let us know which group of people we are watching (“The Bolsheviks”, or “The Traitors,” etc.) or give very basic information on what is going on, but mostly it lets the visuals tells its story. Once again as someone who is not at all familiar with Russian history, the narrative was quite confusing. I know more of this history than I do of Alexander Nevsky, but the details are mostly blank. I’m familiar with names like Lenin and Trotsky, but I couldn’t write you an essay and what all they did or thought. But again, this film wasn’t made for me. Those living just ten years away from the events would have been quite familiar with the details and would not have needed them.

Once again the film’s visual style is just brilliant. Eisenstein has such a visual flair and the ability to juxtapose images together to elicit an emotional response. In one scene, one of the provisional governments leaders is compared to a preening mechanical peacock. In another, images of Jesus Christ is positioned against other religious leaders of the Hindu and Buddhist faiths and then finally to military regalia as if to suggest that all religions are cut from the same cloth and patriotism is just the same.

There is a scene early in the film just as the uprising is beginning where the governmental powers close off the inner city from the peasantry. Bridges are raised and we watch the corpse of a horse slowly rise up and then tumble into the sea. The Bourgeoisie then throw copies of the Bolshevik newspaper into the sea. It is a film worth watching a second time just to better understand the myriad of images thrown together.

I don’t know how to rate either of these films. They are important films in the history of cinema, made by one of the greatest directors from the earliest days of the medium. They are visually stunning and filled with incredibly interesting montages. But they are also propaganda pieces, and frankly, rather dull at times. Alexander Nevsky especially can overwhelm the senses with battle sequences while at the same bore you to pieces.

Both films are being released by Corinth Films on the barest of bare-bones DVDs. There is no information on the prints so I don’t believe any type of restoration was done. Both films look pretty good all things considered, though there is plenty of debris, scratches, and other reminders that these films were made in the early days of cinema. There are no extras, not even a proper DVD menu. The films start as soon as you put them in and if you hit the “Menu” key, you’ll only be taken to a chapter listing.

It is nice to have them in a physical media format, but they could really use a good restoration and some extras would be really nice. An audio commentary or visual essay to detail the plots of these films and their historical importance is sorely missed.

a Rafflecopter giveaway