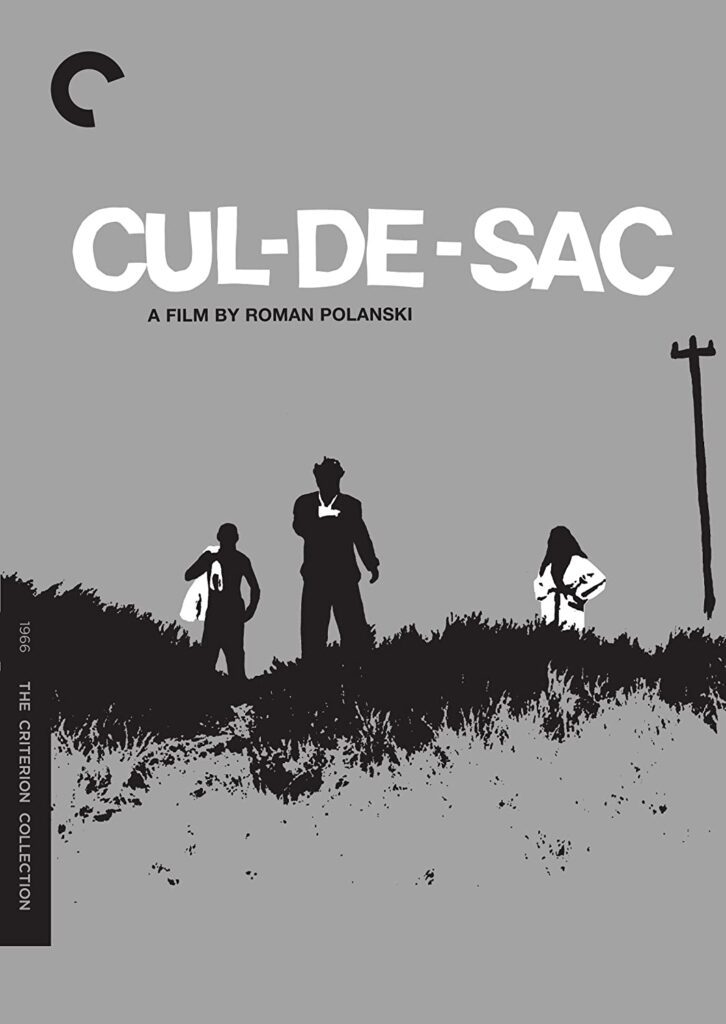

With new releases from The Criterion Collection, the ones I look forward to the most aren’t always the major works or World Cinema or the important Independent releases. The most intriguing are usually the lesser-known works of well-respected directors. When I go down my list of directors that are masters of the craft (meaning that they have control of all aspects from script to acting to filming) – one name that will always appear is Roman Polanski. The man has given us classics in multiple decades: Rosemary’s Baby in the ’60s, Chinatown in the ’70s and The Pianist in the ’00s. The most recent Criterion Collection release is his 1966 film, Cul-De-Sac. I was excited to see this on the release lists because it’s on of the few Polanski films I had never seen – barely even knew about it.

It’s important to place Cul-De-Sac in time and place in Polanski’s career. After the success of his Polish film Knife In The Water, Roman goes to England and is in the middle of a three-film run in three years. In 1965, he did the surprisingly incredible suspense film Repulsion and after this film he’ll go on to do the wonderfully campy take on the Hammer Horror film The Fearless Vampire Killers. In between he films a script that he wrote with Gerard Brach. It’s hard for me to know how to classify the film since it seems to fall within multiple genres – it’s arty, it’s certainly a black comedy, but it seems to ultimately sit within the confines of a suspense plot.

From the first long shot of a car traveling along a beach, we realize that this film is under the control of a director that knows how to tell a story with his camera. The shot moves back to reveal that the car is being pushed and not driven. Through obvious clues, we surmise that these are gangsters of some sort and that there has been a crime that has gone wrong and both men are injured. There is little dialog through the first fifteen minutes of the film as we are given time to familiarize ourselves with the countryside and a castle that serves as a home for a couple. We see this world through the eyes of one of the gangsters – Lionel Stander (who will always be Max the butler from Hart To Hart for me). Lionel plays Richard (aka Dickie), an American gangster who has been wounded in the hand.

He comes upon a large castle that is serving as a home for George and Teresa. George is played by Donald Pleasence (known to most American audiences as both Blofeld from the Bond films and as Dr. Loomis from the Halloween franchise. Here he is portraying an older gentlemen with a shaved head who we see initially with a much younger French wife who emasculates him – first by laughing at him as he tries to cook eggs for his breakfast and second by dressing him in her nightgown and putting eye makeup on him. Teresa is played by the very beautiful Francoise Dorleac – older sister of Catherine Deneuve. The two share an intriguing look (Catherine starring in his previous film Repulsion) that is both youthfully innocent and yet dangerously mischievous.

Dickie has invaded their house to get himself something to eat and to call his boss, Katelbach, to come rescue him and his comrade, Albie. At this point, the film takes a couple turns that reminded me both of the plays of Samuel Beckett and Harold Pinter and of other artistic films of the ’60s. When Dickie tries to return to his car and injured partner, the tide has come in so far that it has isolated them on an island. This isolation of the cast gives the movie a stage-like atmosphere. It’s also a great way to ratchet up the suspense. For one, we know that the characters are stuck together until the tide goes out. And secondly, we are always anticipating the arrival of Mr. Katelbach or his men.

Like a good play, the film spends most of the time drawing on the different couple combinations between the three. Rarely is their interaction between all three in a scene – usually one is off swimming or cooking or asleep while the other two interact. These are scenes where the film follows themes common to many of the Polanski films. Like the isolation felt in The Tenant or Rosemary’s Baby – George has isolated himself and Teresa on this island because he fears losing her. The arrival of Dickie threatens that relationship and he breaks down emotionally at the thought. My favorite scene of the film takes place on the beach as Teresa is off swimming. We see Dickie’s frustration at not being rescued and George’s fear of losing his wife. There’s a bond between the two at this moment that could be read as sexual in modern interpretation but despite the emasculation of George, doesn’t come across that way.

Just when the film verges on turning into chaos – as the violence starts to escalate – there is an arrival on the island. But it isn’t the expected arrival of Dickie’s rescuers; it’s a visit from some couples that worked with George. Included in the arrivals is a very young and very pretty Jacqueline Bisset. This arrival thrusts the plot into more of a dark comedy. There’s the comedic turn of Dickie playing the part of their butler and the way he and Teresa turn against a young boy, Christopher, who scratches her records. The movie becomes almost a farce until the arrival of another visitor, one that we saw kissing a topless Teresa at the very beginning of the film. This lover sends the film careening toward a violent and yet slightly unexpected conclusion. The sexual frustrations and isolation was doomed to end in violence, we just weren’t sure what to expect.

The film is an interesting peek inside the mind of Polanski. He’s working through themes that we will see from him for decades to come. He loves to isolate characters in order to explore deeper emotions. In The Pianist, that isolation becomes a fight for survival. Here it’s an artificial isolation that only lasts while the tide is in. It’s beautifully shot in B&W, which is interesting because the one thing I take from his later films like Fearless Vampire Killers is the vivid colors and complete control of the color palette. The film is ultimately not as satisfying as I would have hoped. The gangster plot is mere window dressing. And the marriage and infidelity plot doesn’t seem to be the ultimate cause of the resolution of the story. Maybe that’s really why the film has such an evocative title – Cul-De-Sac – is it all just a fancy name for a dead end?

The Blu-ray edition has a flawless high-definition transfer. I can’t imagine the film looked this good even in 1966. There is a 2003 documentary on the making of the film and also a television interview with Polanski from 1967. In both cases, I found that there was more attention paid in the interviews to the process of the film than to the deeper meanings of the themes. The booklet essay by David Thompson sheds some light but leaves me feeling like I read an excerpt from what should be a much longer book.