As the 1960s began to close so did the Hollywood studio system. The days when studio heads like Jack Warner could make or break its stars and dictate how they behaved and what movies they made were coming to an end. So too was the Hayes Code with its old-fashioned moral rules about sex and violence dying out.

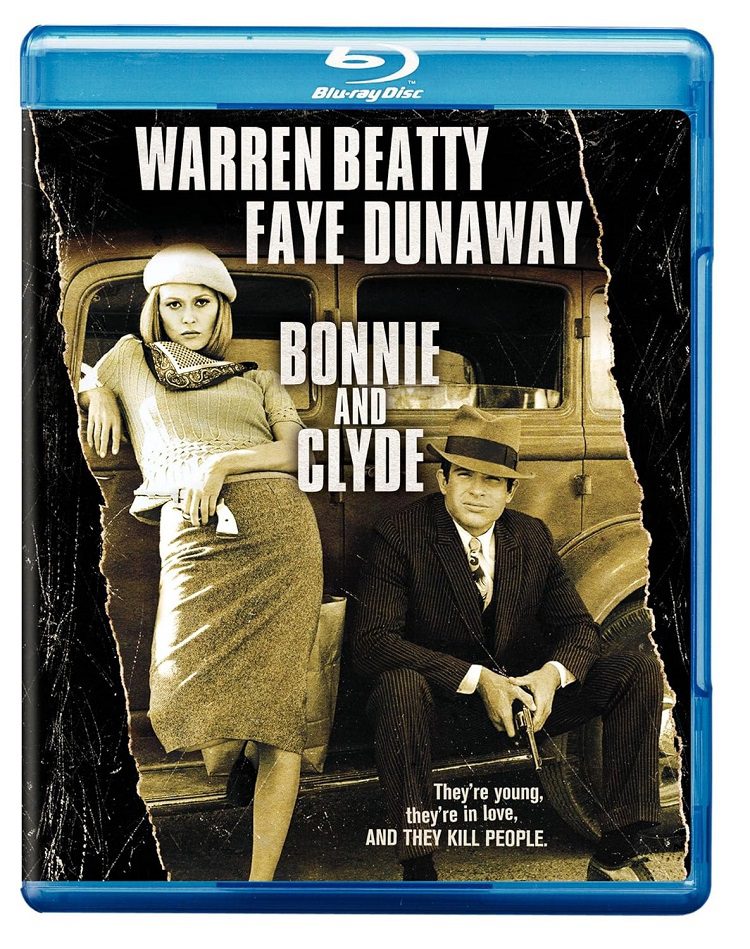

Warren Beatty, who was already a star in 1967, foresaw the dying of the old studio system, produced and starred in Bonnie and Clyde which helped usher in New Hollywood with its new European style and an excess of on-screen sex and violence. In order to get the film made, Beatty took a huge salary cut with a promise of a percentage on the film’s back-end (he did alright, the movie was one of the biggest hits of the year).

Jack Warner hated it and gave it a b-movie release schedule (which meant small theaters and drive-ins). Early reviews from the old-school critics were bad as well. Roger Ebert (in one of his earliest reviews) gave it raves and Pauline Kael wrote a 7,000-word essay for the New Yorker which nearly single-handedly revived the film (and ushered in a new wave of film criticism). From there, the counterculture got a hold of it, and the film returned to mainstream theaters and it became a huge hit.

On its 50th anniversary, I can appreciate the many reasons Bonnie and Clyde remains a cultural icon, has enormous historical significance, and lands on numerous best films of all-time lists. I’m also not afraid to admit that it just doesn’t do that much for me.

That it helped usher in a new wave of filmmaking there is no doubt. It turned two homicidal outlaws into countercultural heroes. Faye Dunaway’s portrayal of Bonnie Parker is uber-cool and oh-so-fashionable (sales of fedoras skyrocketed after the movie). Warren Beatty’s Clyde Barrow is a different sort-of tough guy. He’s good looking, suave, and deadly when he has to be, but also clean, somewhat effeminate, and impotent. He was the antihero for a whole new generation. The film’s iconic ending remains one of the most violent endings to a film ever and is as effective today as it was half a century ago.

Stylistically, it owes a debt to European art-house films and the French New Wave (in fact Francois Truffaut was at one point attached to it). Director Arthur Penn mixes the films bouts of action with scenes of everyday life. The tone quickly shifts from comedic to dramatic, even horrifying, while the editing is casual, almost lazy at time with flawed cuts happening throughout.

I can appreciate all of this while still admit the film drags in the middle. Once the gang is together and they’ve committed the crimes that made them famous enough to have to lay low, I found myself checking my watch repeatedly wondering how much longer there was until the credits. It picks up towards the end but a little tighter editing would have made it much more enjoyable. I hate using the word “dated”, but it is certainly a film of its time. No, that’s not quite right. It was ahead of its time, but 50 years (and countless influences) later, it no longer feels as fresh as it no doubt did upon first release.

But I don’t want to bang the negative drum to loudly. Bonnie and Clyde deserves its place in film history. It’s an important film and a good one. Fathom Events and Turner Classic Movies are offering a chance to see it again this Wednesday on the big screen with a nice intro/outro from Ben Mankiewicz. Get your tickets now.