Sometimes when I can’t sleep, I’ll lie in bed at night and think about all the different houses and apartments I’ve lived in. I’ll mentally walk through each room, picturing what it looked like and describing them as if to a friend. Sometimes the rooms are very clear to me – I can picture it as if I’m there. Sometimes they are more fuzzy and I have to think really hard about what they looked like. Sometimes I can’t remember them at all. There is one house I briefly lived in on Grand Lake whose guest bedrooms are a mystery to me. I can picture every other room but as I mentally move past the dining room, it all gets jumbled together with other houses.

As I’m wandering through the ghosts of old houses, memories of times spent in those rooms float about in the back of my mind. I remember the Christmas Eve at my grandmother’s house on Kates Ln. I recall eating cinnamon toast while watching Thundercats in the house Dad built out in the country. They are just impressions lingering in the attics of my thoughts while I move from room to room.

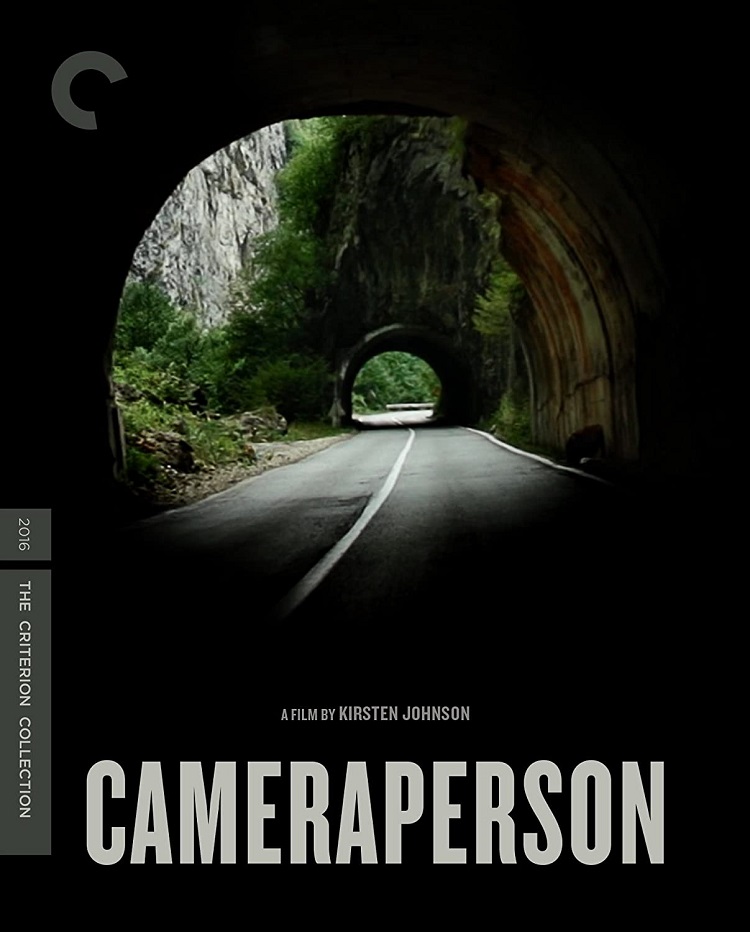

Watching Cameraperson reminded me of those late night memories. It consists of scrap footage from director Kirsten Johnson’s 25 years as a documentary cinematographer. In the opening moment, the text on the screen says that this film is Johnson’s memoir. If autobiography tells the facts of a person’s life, then memoir delves into the emotions that accompany those facts. If this is true, then Cameraperson is very much a personal memoir.

The film brings forth little snippets, tiny scenes discarded from two dozen other films. Much like memories, we rarely get any sort of context for the scenes other than the location. Nor is there any conclusions drawn or closure given. We enter into a moment of someone’s life and then a moment later we are gone. There were times I wanted to pause the film and find a copy of the documentary it came from to learn what happened next.

In Nigeria, she captures a midwife trying desperately to save the life of a newborn baby. She hangs it upside down tapping his back in order to clear its throat and let him breathe. She clears his nasal passages and we hear him cough and cry, finally getting air to his lungs. But he’s not out of the woods. The midwife notes that he needs oxygen but the severely under-equipped hospital has none. Then the film moves on, not letting us know if he survives or dies.

In another scene, Johnson is in Yemeni trying to capture a few seconds of footage of a prison housing al-Qaeda suspects. This is illegal and she could be arrested for taking a photograph. The driver of the car she is in stops at just the right place for her to get what she needs and quickly buys a water from a street vendor to give them an excuse to be there. As they start to drive away, we hear the armed guards yell at them to stop. The film moves on before we see what happens next.

Other scenes find Johnson filming survivors of the Bosnian genocide, a young woman contemplating an abortion, a boxer seen before and after an important fight that he loses, her young twin children playing at her house, two women chopping down a tree for firewood discussing the bastard “Arabs” who made them flee their own homes, her Alzheimer’s afflicted mother, and so much more.

In lesser hands, the disjointed nature of the film would be hard to watch, would find me restless after just a few minutes, but with Johnson’s careful editing I found myself mesmerized, haunted by these scenes of human life shot over several decades from all over the world. There is a great sense of sadness that echoes throughout the movie. Many of the subjects of the various films have lives in peril. They’ve faced violence, rape, genocide, anger, and starvation. In one particularly poignant moment, the translator for the Bosnian documentary contemplates what it means for her to have heard hundreds of stories of extraordinary horror. How can she take all that in and not carry her own post-traumatic stress? There is no answer to that, but Cameraperson seems to ponder Johnson’s own life having documented so much pain.

Yet when she returns to Bosnia five years after her initial visit, she remembers the beauty of the country and the kindness of the families she visited rather than all the terrible stories she heard while there. Memory has a way of softening the pain. Life seeks out beauty wherever it may go.

Cameraperson is a beautiful film filled with violence, horror, and pain. But also love and peace and hope.

Criterion presents Cameraperson with a new high-definition digital master and a 5.1 surround DTS-HD Master Audio soundtrack. As the film culls together bits of more than 20 different films shot in a variety of locations, conditions, and years, there is a noticeable difference in video quality from scene to scene. It was a little distracting at first but quickly I settled into its rhythms and found it didn’t bother me. Both the filmmakers and Criterion have done an excellent job toning some of those edges down. Overall, it looks very good. The soundtrack contains a lot of contemplative silence and largely natural vocal tracks. I never had any difficulty in understanding what was being said.

Extras include a nice feature on the editing of the movie with Johnson and the film’s producers and editors. They obviously did a very thoughtful and careful job putting all of the scenes together to make a very moving film. There is also a roundtable discussion about the film, and excerpts from a couple of film festival talks from Johnson. Plus, The Above, a short film from Johnson, a trailer, an essay from filmmaker Michael Almereyda, and some writings from Johnson.

Cameraperson is an incredible piece of work. Kirsten Johnson has pieced together from the scarps of her other movies something new, fresh and wonderful. Criterion has done a very nice job of presenting it and bringing forth extra material that dig into what Johnson is trying to do with her film.