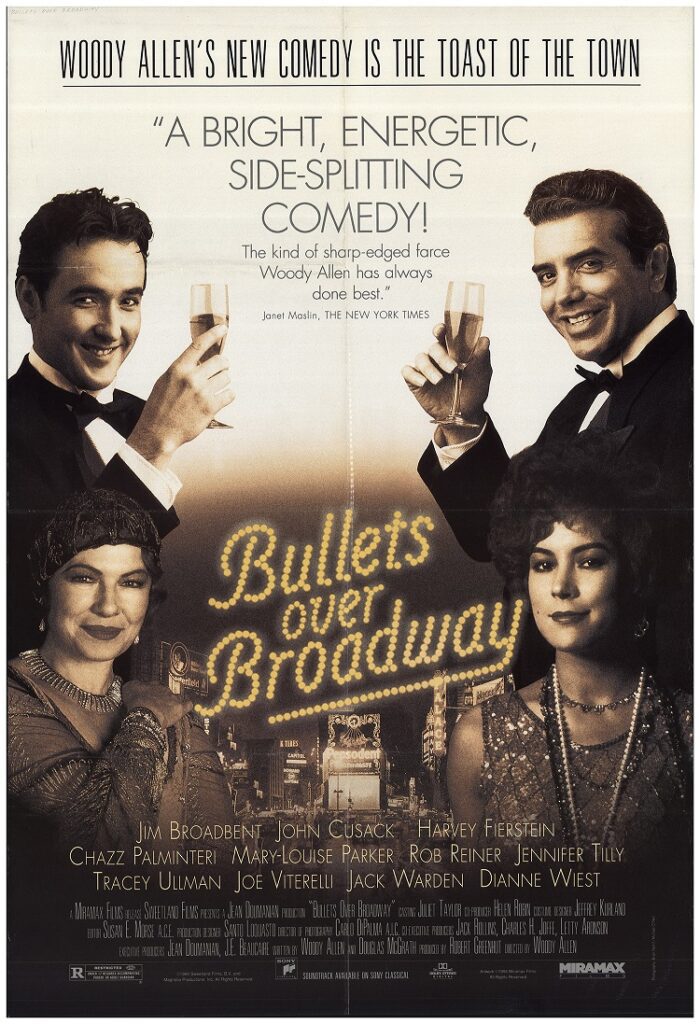

If your memories of the 1994 Woody Allen film Bullets Over Broadway are a bit hazy, there’s a reason: a complicated rights dispute has largely kept the film out of the home-viewing market. If it is remembered today, it’s probably for Dianne Wiest’s Oscar-winning turn as boozy Broadway diva Helen Sinclair, turning on a dime from purple-prosed odes to the magic of the thea-tah to snarled put-downs of her fellow actors, along with her amazing ability to turn the two words “Don’t speak!” into a side-splitting catch phrase.

My memory was refreshed at a May 5 screening of the film, co-sponsored by Film Society of Lincoln Center and Theatre Communications Group (TCG). This was followed by a panel discussion with some of those responsible for turning Bullets into a Broadway musical that has been nominated for six Tony awards. Woody himself wasn’t part of the panel: this was a Monday night, and he has a regular gig playing clarinet at the Carlyle that he’s famously kept rather than attend anything as trivial as the Academy Awards, much less a screening at the Walter Reade Theatre.

The unseen Woody was, however, part of the creative team that transformed his movie (co-written with Douglas McGrath) into a musical, and he was helped enormously by director/choreographer Susan Stroman, who was on the panel. Theater buffs will know her as the genius behind Contact, The Scottsboro Boys, and a minor little smash called The Producers – like Bullets,based on a much-loved comedic movie from Woody’s fellow Your Show of Shows alumnus Mel Brooks. Stroman was joined by lead producers Letty Aronson and Julian Schlossberg; excerpts of the conversation follow.

• Stroman comparing Woody Allen to Mel Brooks: “They’re both geniuses; the jokes just spit out of them, and once we got into the format for each musical and started work, they each wrote new jokes. For Woody, these were gifts for the actors on yellow pieces of paper; it got him all excited to hear the audience’s reaction. Mel is big, loud and leaping around; Woody is quiet, shy and businesslike, but they were both very generous and respectful to me, which in a male-dominated field is remarkable.”

Schlossberg attributed both men’s ability to quickly come up with jokes to their early experiences in live television, shared by fellow comedy geniuses Neil Simon and Larry Gelbart.

• On casting for the musical: Stroman says the team saw as many as 400 men and women as they tried to cast the nine principal roles. It wasn’t just a matter of pleasing both her and Allen, but also finding performers who could act, sing and be funny, all superlatively: “People don’t realize how hard comedy is, and you can’t teach it.”

In addition, Woody himself over-awed some auditioners. One got so nervous that he literally fainted, hit his head, started bleeding and had to be carried out of the audition room. “Woody was calmly sitting there eating a sandwich, and when we came back he said ‘He was good’,” said Stroman.

As for why the cast doesn’t include many big-name movie or TV stars (excepting Zach Braff of Scrubs and Garden State), Schlossberg noted that with a musical, actors generally have to sign for at least a year. Given the rigors of eight shows a week and Broadway’s lower pay scale, many “name” actors are unwilling to do this. “Plus, if you have a musical with Hugh Jackman as the star and then he leaves, sometimes that means the show closes when he’s gone,” said Schlossberg.

•On why the musical uses period songs rather than an original score: Like the movie, the Broadway Bullets uses a grab-bag of 1920s-era popular songs. Aronson says Woody didn’t want to have to pick someone to write new music; Stroman says he did have a preference for songs that were less well-known today so that they could be “discovered” by a new audience. The benchmark for both Stroman and Allen was whether a song moved the plot forward, and both were helped by additional lyrics written by music adapter Glen Kelly, another Producers alumnus. “Glen was able to tailor a score out of all these different tunes, and it’s also somewhat more believable that people would be singing and dancing because it is in essence a backstage musical,” said Stroman.

My own snarky comment after viewing the show, which I saw when it was still in previews, was that it’s a lot easier to cut a number that isn’t working when the composer has been dead for 50 years. Still, the songs are all well-chosen and they certainly fit both the mood and the show’s plot. The best-known number, Cole Porter’s Let’s Misbehave, provides the theme for a great comedic dance duet with Brooks Ashmanskas and Heléne Yorke.

As for how the movie and the musical compare: they do share a theme, namely, is the true artist someone who is willing to die (or to kill) for his art?, as well as a plot and characters, but they really are two different animals – and that’s probably as it should be. Dianne Wiest is delicious on film but Marin Mazzie, the musical’s Helen, is fabulous in her own right. Ditto the delightfully ditzy, nasal-voiced Jennifer Tilly (film) and the stridently sexy York (stage) as the aggressively untalented gangster’s moll, and the film’s Chazz Palmintieri and the stage’s Nick Cordero as playwright-in-the-rough Cheech. All three deserved Tony nominations, but only Cordero got one.

Stroman’s staging is, as usual, a delight: she choreographs not just the superlative dancers but the scenery, lighting and costumes to truly fill the stage. If it’s not the most subtle direction in the world, seeing the film reminded me that the broad style and cartoonish characters have been part of Bullets from the very beginning. And since the film is still hard to come by, visiting New York’s St. James Theatre is probably the best way to simultaneously satisfy your Woody Allen and your Broadway musical cravings. I doubt Annie Hall would make a good musical, but maybe The Purple Rose of Cairo or Love and Death?