Mike Leigh films can be comedies but you’d never put the phrase “light hearted” in front of that description. His films are usually described as “gritty” and “realistic”. The latest Criterion Collection release of his work is Life Is Sweet from 1990, part of what I consider a trilogy of real stories of love and clashing cultures in modern-day England. It is bookended by the under-appreciated High Hopes (1989) and the generally revered or hated Naked (1993). The middle of the three, Life Is Sweet, would seemingly take place in the same universe as the other two. This tale of life and family was Mike Leigh’s directorial breakout onto the international scene, and it’s interesting to look back at a film I haven’t seen since it debuted, now knowing his future works.

The first thing you’ll notice of any Leigh film is his artistic eye for detail. Shots are never random. His characters become so real to the viewer because they are allowed to breathe in the scenes. This is the story of Andy (Jim Broadbent) and Wendy (Alison Steadman) and their twins Natalie (Claire Skinner) and Nicola (Jane Horrocks). The scenes unfold with a slowness like photography more than film. There are closeups of faces and the camera holds looks for seconds. There is a style of improv to the film that works for many people in comedy but is more rare in dramas. But I think it works in these domestic films because it’s harder to script realistic talk amongst family members. Family see and interact every day and there tends to be an overlap and shortcut to their speak that he allows the actors to reach.

Life Is Sweet illustrates Mike Leigh’s balance of political satire with cultural observational humor. This film comes directly at its politics out of the reign of Margaret Thatcher. The heroes of his films are everyday working folks who struggle at work and at home just to keep their lives together. They strive for better lives and are often kept down by the working class. The message is often that no matter how hard the working class tries to change their fate, it will be in vain. The message is just under the surface here and it explodes in Naked.

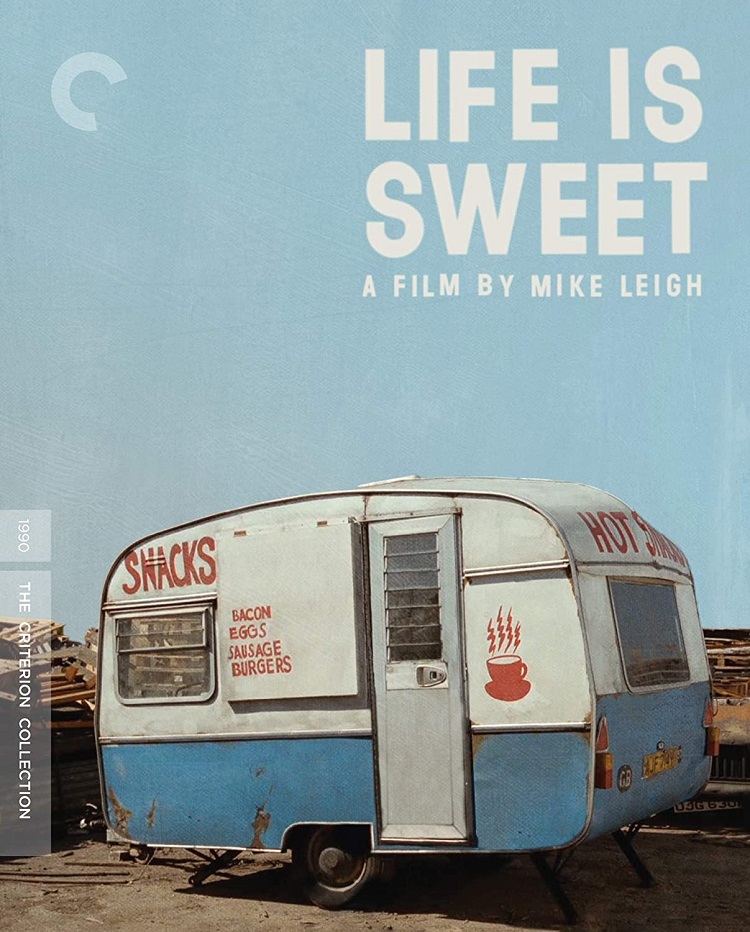

What makes Life Is Sweet more endearing in many ways is the themes of food. The title suggests that life is full of chocolates and sweets. Food plays a major role. It is a part of everyone’s existence. There are the moments of a family simply at home in North London around the dining room table, a broken-down food truck, and the aptly name Regret Rien, a French restaurant that you would regret eating at. Andy, the father, works as a head chef for a sleek, ultra clean corporate kitchen. But Andy can’t work under such conditions and consciously or subconsciously makes mistakes including slipping on a spoon and breaking his leg. He eventually takes a more middle-class route and buys a broken-down food van from a buddy at the bar (Stephen Rea) with the every hopeful middle class plan of fixing it up to make his fortune.

It’s the daughter Nicola who symbolizes the struggles of her generation under Thatcher in Life Is Sweet. Nicola is bulimic. She has been told all her life about how sweet life is but she can’t enjoy any of the food. Jane Horrocks is a discovery in this role. She sells out as a ineffectual teenage radical. She wears t-shirts against Thatcher and shouts the slogans of a radical. But she has no power because she doesn’t eat. It works as a great symbol for the feeling of late teens and early twenty-somethings. It’s also a symbol of the youth in the UK as the winds of change made them feel even further out of touch with society. She is fascinated with chocolate – hoarding bars in her room that she can’t eat and forcing her boyfriend (the creepy David Thewlis) to tie her up and lick it off her instead of sex.

There’s a solid family bond at the heart of Leigh’s film. Nicola’s behavior brings the family together to try to save her. But this isn’t the sappy ending of a mainstream American film about families. Leigh lets it play out with anger and humor. The parents are frightened for her future. It takes a quiet moment between twins (and the symbol of their link) Natalie and Nicola to lead us to the end of the film. There comes the debate. The future is only hinted at; there are no conclusions. We watch Nicola’s face and body language hoping that she saves herself. But there’s always a little room for doubt.

The disc fits right with other Criterion Collection Blu-rays. It is filled with a collection of extras to make you an expert in Mike Leigh. There’s a new commentary by him and a recording of a 1991 interview. There’s an informative essay by David Sterritt and most interestingly five short films that Leigh did for a proposed “Five Minute Films” television series.

The viewer is in good hands with Mike Leigh writing and directing. His tale of ordinary lives belies the love that lies below the surface. These folks help each other in the end, even if their dreams are more modest than others of a higher birth. The actors bring this film to life and you won’t want to leave them so early. And you’ll hope that the world will be a little better to them. Be a little sweeter, if you will.