There are a few iconic things that come to mind when someone mentions Total Recall (1990) — Mars, over-the-top effects, explosions, false-memory implantation, and the mutant prostitute with three boobs. One of these is noticeably absent from the 2012 reboot of the movie of the same name based on Philip K. Dick’s short story We Can Remember It For You Wholesale. Can you guess which one? You might be surprised, and then surprised again to learn that it was never really featured in the original short story, either.

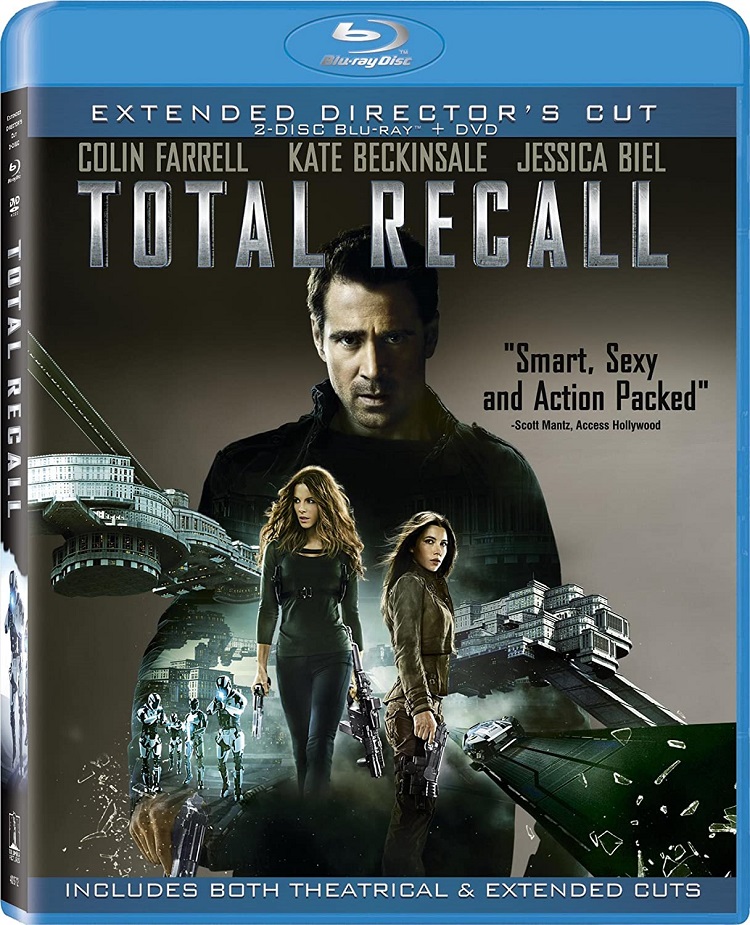

For those who are just joining us, Total Recall is the story of a man who lives an ordinary and uninspiring life with his super-hot wife (Lori played by Sharon Stone [1990] and Kate Beckinsale [2012]), but has vivid dreams of and ambitions of being and doing something greater. He learns of a company (Rekall) who can implant memories that give people the experience of having done something without the encumbrance of cost, time, or other arrangements. The customer sits in a chair, the implantation process is executed, and he or she wakes up remembering this great vacation or adventure or what-have-you. In the 1990 version, the protagonist Quaid (Arnold Schwarzenegger) wants to pursue these dreams he has of tracking down an alien artifact on Mars. In the 2012 version, Quaid (Colin Farrell) dreams of fairly vague espionage and spy games involving a woman named Melina (Jessica Biel, previously played by Rachel Ticotin), which tells you very little about what’s to come. To me, the foreshadowing in the 1990 version gave a little more oomph to the events to follow.

While there are a number of similarities, this is not a scene-for-scene remake. Several familiar elements are here, including the mid-movie stand-off where an attempt is made to convince Quaid that he’s just living the memory while still strapped in the chair at Rekall and needs to help make it stop before he gets lost forever in his own mind. On the other hand, the way things play out ranges from simply updated to use slicker gadgets to being completely different from one version to the next. Cell phones built into one’s hand, hover cars, The Fall (a device used for intraplanetary travel between Britain and Australia), and an army of robot police (a.k.a., the synthetics).

Here are a few examples of things that have changed over the last 22 years, with some inevitable spoilers:

- In the 1990 version, when Quaid meets the dream woman in real life, she wants nothing to do with him and suspects him of working for the other side, and needs some convincing before wanting to help him. In the 2012 version, she actually helps him escape the police at their first meeting and makes every effort right away to get him in touch with the leader of the resistance.

- In the 1990 version, the leader of the resistance is an alien hiding in a man’s body, a reveal scene that anyone who has seen the movie will remember well. In the 2012 version, the resistance leader is just a man, and a largely unremarkable one at that. I’m surprised they got Bill Nighy to sign on for such a bland and short-lived role.

- The dreams in the 1990 adaptation are of Quaid on Mars on a mission to find and use an alien artifact of great power and benefit to the Martian colonists. In the 2012 version, the “secret” embedded in Quaid’s mind is some sort of code used to deactivate all the sythetics in the army that’s being sent to destroy the colonists in Australia. SPOILER ALERT: The code actually doesn’t exist though, while the 1990 Martian artifact DOES exist. This “twist” actually weakens the newer movie somewhat since the whole first half of the movie seems like a dim-witted double-cross with nothing actually backing it up.

- In 1990, Quaid reacts before the memories are implanted, is subdued, mind wiped, and sent home in an automated taxi cab. He doesn’t really remember much of anything at that point, which makes the attacks by his wife and other heavy hitters all the more mystifying to him. In the 2012 version, Quaid leaves Rekall with memories intact and being chased. However, neither of these explains as eloquently as the source story how every time they go to give Quaid a new memory of something, they keep finding out that it’s already there.

- In the 1990 version, Quaid is handed a briefcase by a stranger that gets him on his way in the quest. In 2012, he receives a strange and cryptic phone call on a device implanted in his hand he doesn’t seem to know was ever there. The message leads him to a safety deposit box that contains basically the same information as the briefcase from the original movie. The transmitter/phone in his hand serves the same function as the cranial implant Quaid had to remove in the 1990 version, a scene that has also become synonymous with the movie. The 2012 device removal is unremarkable; he just cuts his hand and pulls it out. Schwarzenegger did it better.

- During the stand-off where Quaid is asked to do something to awake from this dream/memory he’s living out, he’s asked to resolve it two different ways — in 1990, he has to take a pill, whereas in 2012, he’s asked to shoot and kill the woman helping him.

- 1990’s Quaid kills his wife about halfway through the movie, and he is pursued by Richter (Michael Ironside), her real husband. 2012’s Quaid is also told that his marriage is a lie, but his “wife” is actually unmarried, assumes both character roles of the wife and the pursuer (i.e, Richter), and SPOILER ALERT survives all the way to the end to make one of the most nonsensical “one last lunge by the bad guy” scenes I’ve ever seen. At that point, her cause is lost, her commander dead, and she’s surrounded by people who would have her head on a spike for trying to kill the good guy. She has no motivation to do so at that point, but stupidly tries to do it anyway.

- 1990’s mutant prostitute with tricera-tits is one of many mutants on Mars, having suffered as a result of poor shielding from radiation. The three-boobied hooker in the 2012 retelling shows up randomly in a more risque part of town on Quaid’s way to Rekall.

The major themes of the original movie are the uprising of a class of people who has been not just ignored, but actively marginalized and crapped on, treated as less than human ever since they arrived on Mars. They want to rise up due to inequal rights and working conditions. In the 2012 version, there really is no uprising, just some unhappy plebians, or “temporarily embarrassed millionaires” as Steinbeck put it. The resistance barely even exists, and is trumped up by the government to be something much worse than they really are. The ruling class holding all the power and wealth forces the lower class to work double shifts occasionally in an otherwise clean and safe environment with food and water for all. It’s easier to root for people who are growing a third eyeball or whose skin is melting off due to horrible conditions than it is for people with what appear to be nothing more than a slew of first-world problems they seem largely okay with; the government just wants to kill them all because, and take their land back.

Even the hooker with three boobs in the original movie fits there better because she’s surrounded by other mutants who are doing their best to cope with their living conditions and physical abnormalities. She develops a mutation that makes her unique in her industry, and she’s capitalizing on it to try to make ends meet in an an utterly destitute world. The 2012 hooker appears out of nowhere, lends nothing to the greater context of the story, and there’s no explanation or justification for why she looks the way she does. Yes, that hooker was actually symbolic before; now she’s just window dressing.

If you haven’t guessed by now, Mars is the one major element of the previous story that’s missing this time around, save for one brief mention of it early in the movie. I kept wondering if they were going to shoehorn it in toward the end, but it didn’t happen, and really wouldn’t have made any sense at that point if they had. The original short story never left Earth despite the original Quail’s (not Quaid) fantasy of visiting Mars and asking for such a memory to be implanted, so technically that aspect was more accurately portrayed in the newer movie. In the end, both are loose adaptations on the original short story, and take some generous liberties along the way that make them stand out in their own unique ways. However, the plight of the suffering in the original gives the audience a much bigger injustice to root against than the nonexistent problems of the poor trying to climb their way up out of the financial doldrums.

One other distinct difference is the rating. The original Total Recall went for a solid R with graphic violence, nudity, and sexuality at every turn, all trademarks of director Paul Verhoeven, also known for the edgy movies Basic Instinct, RoboCop, and Starship Troopers. This time around, Len Wiseman is at the helm, director of 2007’s Live Free or Die Hard, the only Die Hard movie thus far not to be rated R. Wiseman saw to it that this version of Total Recall manage to stay within the tidy confines of a PG-13 rating, despite using the word “fuck” and showing exactly three bare breasts in the process, two things that could have landed it squarely in R territory in another time and place. However, this means the gunplay is more subdued and injuries implied, for better or worse. Moments like a rat being shot and its entrails exploding on a video monitor are definitely absent this time around.

Various parts of the new version reminded me of The Fifth Element; I, Robot; and even Aliens. Pretty decent company to be in. They committed to making the environments — both the tangible-near and the CGI-far — look dirty and worn and lived in, not all pristine and shiny and plastic like the backdrops of many sci-fi movies, particularly the Star Wars prequels. The chases are fun to watch, the shootouts exciting, and the effects are second to none. If you’ve never seen the original, this is a decent ride. If you have and you are coming in with expectations, it’ll meet you about halfway. Your satisfaction at that point depends greatly on whether you’re willing to accept the differences between two otherwise pretty good action flicks.