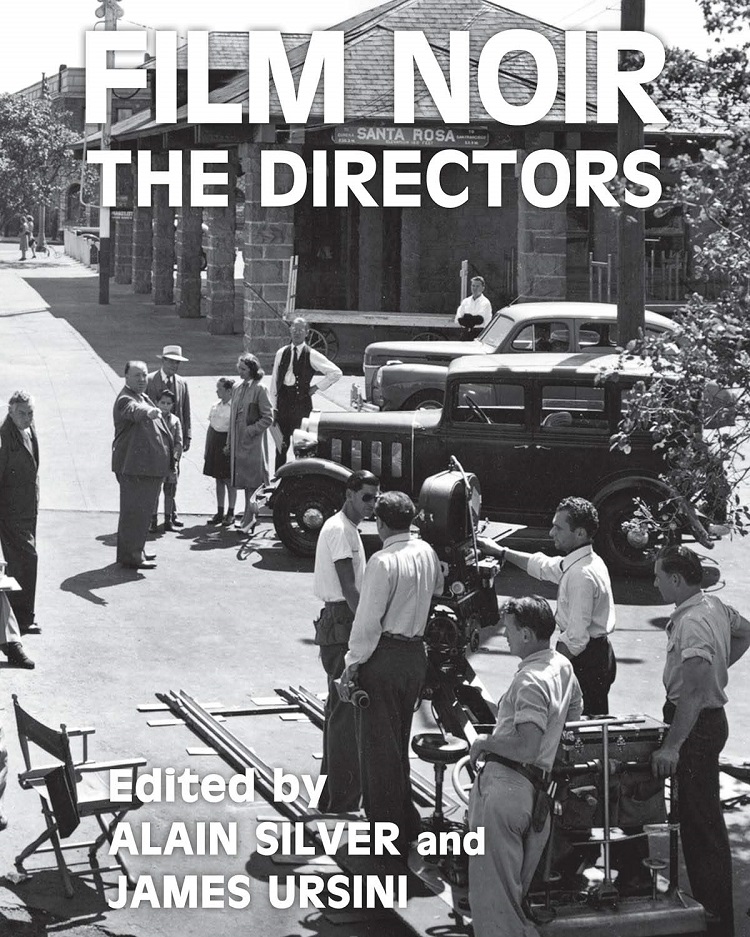

Film critics Alain Silver and James Ursini are responsible for the brilliant four-volume Film Noir Reader series. Their latest outing is titled Film Noir: The Directors, and is a compilation of essays from over two dozen of their peers, focusing on 30 key directors from the classic period of film noir. The book includes short biographies, lists of their major noir films, and analysis of the films themselves.

The classic noir period is generally considered to be between the years 1941 and 1958. The date is somewhat fungible however, as the movement basically grew organically out of various sources. For example, the great German director Fritz Lang is credited with creating much of the basic language of the genre as far back as 1921. Most scholars consider John Huston’s The Maltese Falcon (1941) to be the first Hollywood film noir production though.

To say that Huston’s was an enormous talent is an understatement. Still, it is somewhat hard to believe that The Maltese Falcon was his first directorial effort. Starring Humphrey Bogart as Sam Spade, and featuring Mary Astor, Peter Lorre and Sidney Greenstreet, this taut picture made for one hell of a debut. It was enormously influential, and there would soon be a great number of similarly themed movies in its wake.

One of these would be Robert Aldrich’s Kiss Me Deadly (1955). Like The Maltese Falcon, Kiss Me Deadly is considered definitive, but it was not Aldrich’s first foray into the genre. His earlier World for Ransom (1954) and The Big Knife (1955) are both discussed in some detail as necessary precursors to his indelible masterpiece.

Besides Lang and Huston, there are some other, very well-known directors profiled in the book. These include Alfred Hitchcock, Orson Welles, Otto Preminger, and Billy Wilder. All of these directors are responsible for excellent entries in the noir genre, although these films represent just one aspect of their wide ranging oeuvre. Welles’ is an interesting example. Nobody can argue that Touch of Evil (1958) does not belong in this book, in fact it is often cited as the final noir of the classic period. But Citizen Kane (1941)? The authors make a strong case for it, and I have heard others mention it as well, although I personally am not convinced.

Still, it is this type of discussion that makes Film Noir: The Directors such an interesting read. The authors make all kinds of interesting connections between the various films at hand. Some are obvious, some not so obvious. In the end, there are no “right” answers, but there are an enormous amount of informed observations presented. And that, I think is what us film geeks live for. This is a great book, and I think it works not only for fans of noir, but of excellent film criticism in general. Well worth checking out.