The opening shot of 3:10 to Yuma (1957) sets the film up as perfectly as anything I have ever seen. It features a magnificent panorama of a stagecoach on the plains of the Old West, accompanied by the deep voice of Frankie Laine intoning the words, “There is a train called the ‘3:10 to Yuma’…” The combination of the vistas and the dramatic music are incredibly powerful, and as the coach passes in front of the camera, you just know that this will be a classic Western fable. That was my experience the first time I saw the film, and I get the same chill every time.

That first time was relatively recently, in 2007. Although I did not know it at the time, Encore Westerns were airing the original in anticipation of the Russell Crowe remake. To be honest, I just flipped over to it because there was nothing else on at the time, but I was hooked immediately. The original 3:10 to Yuma is a fantastic movie, as good as such celebrated Westerns as The Searchers (1956) or High Noon (1952), yet has never been acknowledged as such.

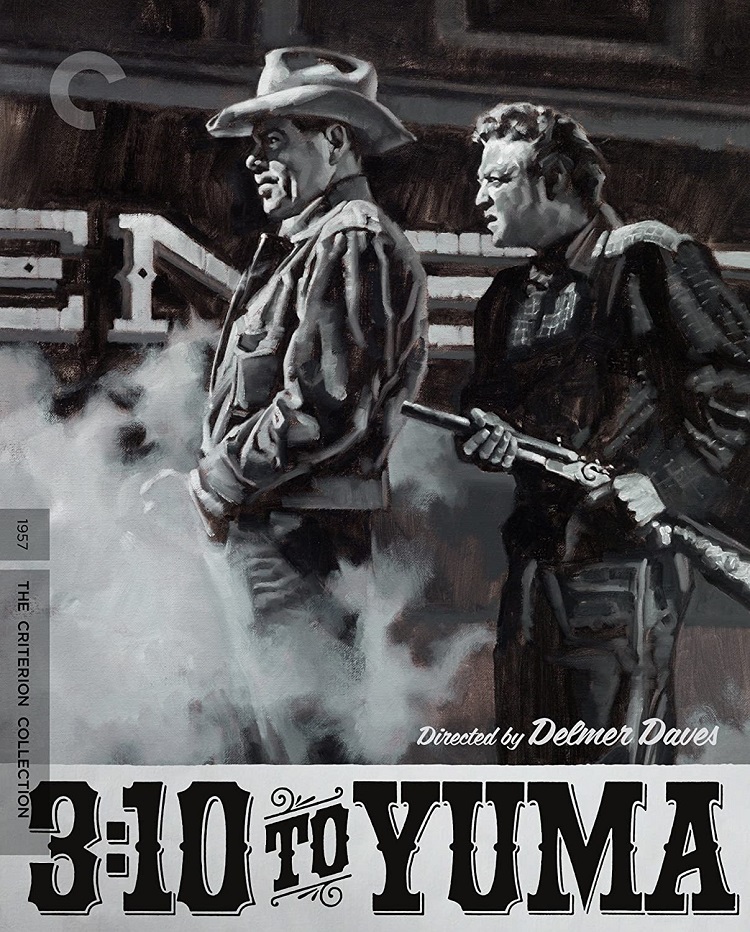

It is gratifying to see 3:10 to Yuma enshrined as part of the Criterion Collection. The genre has always had a tough time with critics. I think a lot of this has to do with a perception that Westerns are not “serious films,“ and the thought that the main audience for them are reactionary rednecks. John Ford is one of the few Western directors who has been recognized as an auteur, and I believe that Delmer Daves’ Yuma is right up there with anything by Ford.

The stagecoach that we see in the opening shot is forced to stop by a herd of cattle blocking the road. There are a gang of riders surrounding the herd, and when the coach stops, they pull out their guns and rob it. Their leader is Ben Wade (Glenn Ford), and when the driver goes for his gun, Wade shoots him. He then shoots his own man, who was guarding the guy.

Rancher John Evans (Van Heflin) and his boys see the commotion from afar, and ride up. It is Evans’ herd that have been used in the holdup. When Wade takes the Evans’ horses, they are forced to walk home. This is truly a walk of shame for Evans, who is humiliated in front of his wife Alice (Leora Dana) for allowing the situation to happen. “What was I supposed to do?” he asks, as she turns away in barely concealed disgust. They are broke, and ready to lose the ranch. When the offer comes for “volunteers” to get the gang, with a $200 inducement, Evans immediately signs on.

The tight construction of the movie hinges on moments, and a great one comes when Wade’s gang ride in to the cow-town of Bisby for a drink. They line up at the bar, where a beautiful barmaid named Emmy (Felicia Farr) walks up and down the line pouring shots. The scene is amazing, with the camera looming above the men, then slowly following Emmy’s every action. To get some alone time with her, Wade reports the robbery. He says that he and his men were on a cattle drive and saw it all happen. The men of the town form a posse to chase down the robbers, and Wade sends his own men off as well.

At this point, 3:10 to Yuma has already defined itself on one level as a study of what men will do for the women they desire. Both Evans and Wade risk their lives. Wade would have gotten away clean had he not stopped. For Evans, it is a far deeper matter. His entire self-worth is at stake here; it is his manhood that he must reclaim. As we soon discover, the $200 does not really even matter.

When the posse figures out that the “cowhands” were actually Wade’s gang, they form a plan. Evans and town drunk Alex Potter (Henry Jones) will guard Wade until he can be put on the 3:10 train to Yuma, Arizona. To foil his associates, they will hide out at Evans’ house, then go to the wonderfully named Contention City to board the 3:10.

The second act of the movie revolves around all of the psychological games that Wade plays with Evans. This is the third time I have watched the film, and I pick up new things every time. It would spoil it to give them away, but the cat-and-mouse game is fantastic. The dutiful rancher is so far out of his league with the outlaw leader that it is almost laughable. Yet Evans, as played by Heflin, exudes a quiet dignity that Wade comes to deeply admire, although he would never admit it. Evans is offered ever-increasing sums of money by Wade to just drop the whole thing, and ignores them all. The clincher comes when the owner of the stage, Mr. Butterfield (Robert Emhardt), tells him that he will pay him the $200 anyway, and to just led Wade go, rather than lose his life in taking him to the train.

Evans refuses to abandon his mission, even when his wife begs him. She apologizes for what “he might have thought she meant” earlier, but we know what she meant. This job is about reclaiming his dignity, which is one thing money cannot buy. My impression is that the hard-to-believe ending of the film is the reason 3:10 to Yuma has not been canonized over the years. But the ending is perfect, for this is ultimately a tale of redemption. It takes a careful hand to make the situation not only believable, but inevitable. Daves makes Wade‘s actions a mark of respect for the relationship that has been carefully built up between the two characters. For those who have seen the picture, let me just affirm what a magic moment it is when Wade shouts out “You gotta trust me on this one!’ at the climactic moment. If you have not seen it, then by all means, you need to.

By the way, after seeing the original, I decided to check out the 2007 remake, which was directed by James Mangold. It is perhaps the worst “update” I have ever seen. Mangold takes out every nuance of Daves’ film, in favor of obvious (and pointless) action sequences, and his ending makes no sense at all. In the bonus interview with writer Elmore Leonard, he calls this version “terrible,” and he is absolutely right.

The Criterion Collection edition of 3:10 to Yuma is a single DVD, with two bonus interview features. The first is the previously mentioned interview with Leonard, who wrote the original pulp-Western story (13 min). The second is with Glenn Ford’s son Peter Ford (15 min). Both interviews were conducted in 2013 specifically for this release.

There are a lot of people that I come in contact with who say that “cannot” watch old, black and white movies. It can be a battle to convince them that some of these (like Yuma) are better than anything they will ever see on IMAX or 3-D. I used to think that John Ford had forever defined the Old West with his use of the towering rock formations in Monument Valley. Daves actually manages to challenge this perception by using his own, equally stunning vistas. The way the camera captures this desert scenery in 3:10 to Yuma is magnificent, as is the story. Forget classic Western, 3:10 to Yuma is a classic film, period.