The stifling, claustrophobic feeling director Sidney Lumet perfected in films such as Dog Day Afternoon (1975), and Network (1976) was a key ingredient of his directorial debut, 12 Angry Men (1957). The premise of Reginald Rose’s script was a deceptively simple method of conveying the raging emotions of the 12 jurors who are tasked with deciding a murder trial. It is a blisteringly hot day in New York City, there is no AC, and the dilapidated fans in the room do not work. All anyone wants to do is leave, but they have one little matter they must resolve before adjourning. Guilty, or not guilty.

At first, things look promising – especially for the Yankees fan who has tickets to the game. The initial vote comes in at 11-1 guilty, with Juror 8 (Henry Fonda) the lone holdout. The other jurors turn to him, and try and convince him to vote guilty, so they can all go home. While Fonda is not convinced of the suspect’s innocence, he is not convinced of his guilt either. And so the deliberations begin. Step by step, they go through the trial, and in doing so, more and more is revealed about each juror. This is a powerfully effective expository device, as it shows that this “jury of peers” are anything but. In a larger sense, it shows that the whole concept of trial by a jury of equals is a wonderful ideal, but does not really exist in practice.

One detail that emerges early on is that the accused is a young black male, with a record of petty crime. He is on trial for the murder of his father. The 12 middle-aged white male jurors cannot relate to his life in any way, as they readily acknowledge. In 1957, the civil rights movement was just beginning to gain traction, and some of their comments speak to the prejudices of the time. Statements such as “We know how those people are,” or some of the descriptions of what life in the slums is like, speak to the ingrained racial beliefs these men hold. Juror 10 (Ed Begley) is the worst, his racist tirade towards the end of the film repulses everyone else in the room.

As Fonda and the others begin to dissect the evidence they had been presented, they begin to realize just how circumstantial the case is. It also begins to dawn on them that the young man’s court-appointed lawyer may not have had any real motivation to mount a vigorous defense. This, along with the basic principles of the American justice system – such as “innocent until proven guilty” and the concept of reasonable doubt are also explored. With the understanding that it takes a unanimous vote of guilty to send the accused to the electric chair, the case becomes deeply personal. Their votes do count, and a man’s life hangs in the balance. The early, apathetic mood of the room changes, and becomes electric as each fights himself and his fellow jurors to try and reach a conclusion they can live with.

Lumet’s use of camera angles, and the actor’s periodic displays of passionate emotion provide the only “action” in the film, and they combine to make it surprisingly compelling.

12 Angry Men was a marvelous debut for Sidney Lumet as a film director, but it was all there in Reginald Rose’s script. Actually, Lumet had an incredible template to work from as well with the original Studio One television production of 12 Angry Men. This was broadcast live on CBS in 1954, and directed by Franklin Schaffner. As part of the two-DVD Criterion Collection edition, the program is included as an extra, and it is something to see. If you have ever wondered why those years are always referred to as “The Golden Age of Television,” this is one of the reasons. One of the key components of both the broadcast and film versions of the story is the way the camera is used. To make the type of rapid-fire cuts and edits Schaffner did in a live setting like this was an amazing feat.

Before Lumet and Rose collaborated on the theatrical version of 12 Angry Men though, they worked together in live television. Tragedy In A Temporary Town was broadcast as part of the Alcoa Hour in 1956. It was written by Reginald Rose and directed by Sidney Lumet. Tragedy In A Temporary Town is also included in the set, and thank you, Criterion, for adding it. The story takes place in a company town – possibly loggers, perhaps miners. Everyone lives in small, tacked together shacks, many miles away from any official scrutiny.

In the opening scene, an unidentified male shouts “Hey,” quickly plants a kiss on a 15-year-old girl, then runs off. She screams long and hard out of simple fear, and the consensus immediately becomes that she had been raped. And then the mob mentality takes over. Rose’s metaphor for McCarthyism and blacklisting could not be more clear. Even 55 years later, the horror of what a mob is capable of doing is frightening. Lloyd Bridges gives a brilliant performance as the only voice of reason in the camp.

The remainder of the extras feature interviews with various personalities associated with Sidney Lumet, Reginald Rose, and director of photography Boris Kaufman. There is also a production history of 12 Angry Men and the original theatrical trailer.

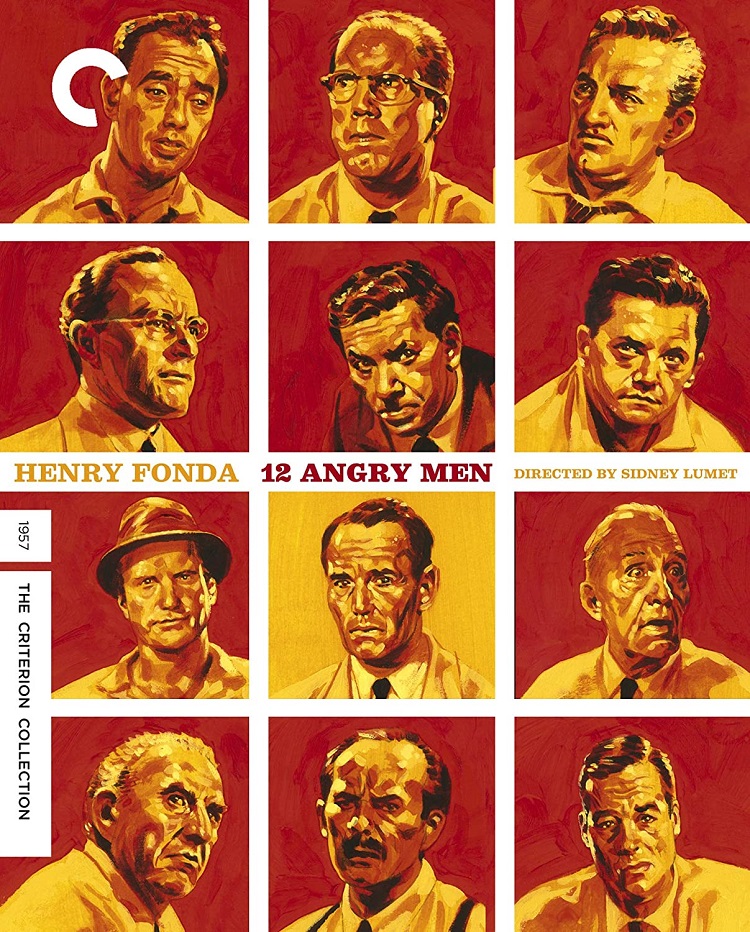

12 Angry Men caught the country at the very cusp of the Civil Rights movement, and is an indicator of the explosions to come. It is also a masterfully directed piece with nothing but the emotions of the players to provide the action. The fact that it remains a compelling film from start to finish is a testament to the talent of the young Sidney Lumet. It is hard to believe this was his directorial debut, for he has already mastered the form. For these reasons and more, 12 Angry Men is a cinema classic, and a fine addition to The Criterion Collection.