German cinema during the ’70s belonged to Rainer Werner Fassbinder. The director was incredibly prolific from an annoyingly precocious age. He directed his first feature when he was 22, died when he was 37, and in that 15 years he made over 40 films and TV productions, all while directing plays and living the sort of wild hedonism that, well, leaves you dead at 37. Along the way, he built up a kind of commune/repertoire of actors, filmmakers, and hangers-on, all working on various projects. One of these was Kurt Raab, an actor and production designer who was deeply interested in the Fritz Haarman murders of the ’20s. Haarman accumulated colorful nicknames like The Butcher of Hanover, The Vampire of Hanover, and The Wolf Man. A homosexual pedophile murderer and cannibal, he was convicted of 24 murders, claimed to have done many more, and was executed in 1925 for his crimes.

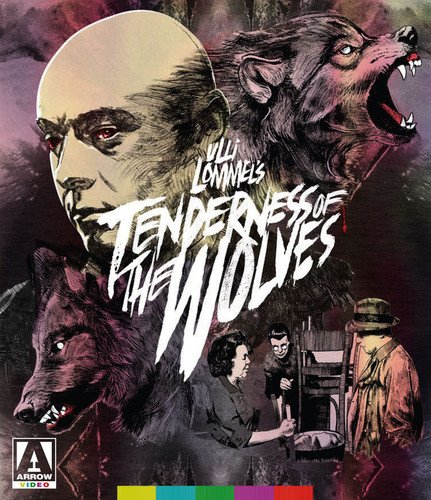

His story was a partial inspiration for Fritz Lang’s classic M, and sounds like a good basis for a creepy, disturbing horror movie. While Tenderness of the Wolves (which has also the been translated as The Tenderness of Wolves) is indeed creepy and disturbing, it would be a misnomer to call it a horror film. It belongs more to the very specific genre of New German Cinema that Fassbinder pioneered in the ’70s, which combined a social realism contrasted with a Hollywood style Romanticism. The color pallet of these movies tend toward gold and brown – weirdly comforting visuals that are interrupted by uncomfortable stabs of cold light and color.

And they rarely came colder than Tenderness of the Wolves. While it is reputedly based on close readings of the case files of Fritz Haarman, the reality of the production (where there was nearly no budget and very little time, which made a ’20s period drama impossible to realize) forced the movie to be set in the post-WW 2 period. Work and food were equally scarce, and criminals had as hard a time scrounging around as anyone. Fritz Haarman was one of these criminals – his boyfriend was some low-level pimp, his friends were all scammers or whores of some variety, and they all knew that Fritz had his penchant for little boys, which they made jokes about.

Fritz is known to the police, but, as one of the cops explains “times are hard for the police, too.” Rather than run Fritz in as a homosexual (which was illegal at the time in Germany) or a pedophile or any of the various crimes they know he’s committed, it was more convenient to recruit him as an informant. The police would look the other way at his crimes if he would keep them informed on anything big going on.

What they didn’t know (or did not want to know) was that the real crimes they were turning a blind eye to were inhumanely monstrous. This becomes clear to the audience (assuming they don’t know the background going into the show) when Fritz brings home a boy, gets him drunk – then chokes him into unconsciousness, bites open his neck, strips him naked and smears his own blood all over his body as he dies.

Beyond the graphic nature of the scene (and Tenderness of the Wolves has rather copious full frontal male nudity, and in a couple of scenes lots and lots of blood) what’s remarkable is what happens next. Two different guests come into Fritz’s room while the boy lays naked, cold and dead on his bed, and both of them are willing to believe Fritz’s transparent lies about him just being asleep.

They like Fritz. He’s a friend, he has an in with the cops, and he occasionally has money. And he somehow has access to the best, freshest sausages in town.

The movie never graphically depicts Haarman butchering his victims, but it is implied rather heavily. And nobody seems to want to question where Haarman is getting this meat from. Or why boys are disappearing in town. Or anything that would interrupt their world, even as miserable and uncomfortable as it is. This strange form of social sanction and intentional ignorance is as much a subject of the film as the murder and the cannibalism.

Kurt Raab plays Fritz with an ingenuousness and a soft kind of charm, but his shaved head makes it hard not to see him from the beginning as a kind of nosferatu. The rest of the cast is filled with Fassbinder regulars, including a small part played by Fassbinder himself. The film shares a lot of aesthetic elements with other Fassbinder films being made at the time, but the interviews and commentary new to this Arrow Blu-ray release make it clear that this was a film primarily made by Kurt Raab (who also wrote the movie and did production design) and Ulli Lommel, not something puppet-mastered by Fassbinder.

Indeed, if Ulli Lommel is to be believed, until it achieved critical acclaim Fassbinder didn’t want his name directly associated with something this violent and upsetting. Only after it was clear the movie was something of a masterpiece did he suddenly give himself an enormous production credit, right there as soon as the credits open.

And calling it a masterpiece is not going too far. It is a moody, strange piece that feels like a sober art movie right up until Fritz Haarman bites open a young man’s neck. And then, it does not do what other “shocking” art movies have the tendency to do, which is then wallow in the shock and violence to make some kind of point by rubbing the audience’s nose in degradation. The horror here is shot in a rather naturalistic style. When the film is obviously going for affect, it can become more expressionistic in lighting and sound design, but it never does so in the depiction of the violence.

This technique is discussed in length in the numerous extras available on this fine Arrow release. There are interviews with the director, Ulli Lommel, the cinematographer Jürgen Jurges (whom, according to Lommel, Fassbinder wanted fired just for stuttering, but who ultimately shot several of Fassbinder’s most celebrated films) with the actor who played one of Fritz’s victims, and an extensive video appreciation by critic Stephen Thrower. Thrower thankfully addresses Ulli Lommel’s strange filmography, and how a man can go from making a film of obvious quality like Tenderness of the Wolves to being a purveyor of direct-to-video shlock like Zombie Nation and Son of Sam. Thrower admits he hasn’t seen any of the latter-day Lommel films – I have, and they richly deserve their terrible reputation.

Just as Tenderness of the Wolves deserves its much loftier reputation. The film is not structured like a thriller. We do not have investigations leading to more clues and the tightening of a noose around a devilishly clever killer. Fritz isn’t that clever, the world around him just doesn’t care that much. Tenderness of the Wolves explores not just the inner world of the murderer, but the society in which he can operate, freely, and that is in many ways just as dark and terrible as he is.