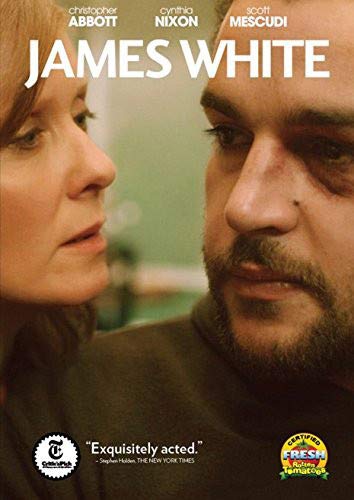

For the first 20 minutes or so, James White is an oppressive experience. In its first quarter, nearly every shot of Josh Mond’s feature directorial debut is a close-up or closer, with just a couple medium shots sprinkled in here and there, and in most of them, it’s Christopher Abbott’s bleary visage that dominates the frame.

Abbott stars as the titular James, a guy whose shitty run of luck is matched only by his self-destructive impulses. His estranged dad has just died, and when he’s not forcibly ejecting guests out of his mother’s (Cynthia Nixon) Upper West Side apartment during the wake, he’s out drinking and picking random fights, accompanied by best friend Nick (Scott Mescudi, better known as Kid Cudi), equal parts mediator and enabler.

The visual gambit is on the verge of becoming unbearable when James suddenly announces he’s taking a trip to Mexico to get away from his mess of a life. Cut to the film’s first wide shot — James is standing in the ocean, just a small dot at the center of the frame, surrounded by tranquil beauty. On its own, there’s nothing special about the composition, but taken in conjunction with everything that’s come before it, it’s almost a sublime moment of relief.

While on vacation, James meets fellow New Yorker Jayne (Makenzie Leigh), and falls into an easy romance with her, and the film’s woozy camerawork begins to signify something distinctly more pleasant than it did in the beginning. But this is a miserablist tale, so naturally, the good feelings are fleeting, dashed completely when James receives word that his mom’s aggressive cancer has returned.

When the film focuses on James and mom Gail’s coming to terms with her illness, it’s riveting, particularly thanks to Nixon’s rueful performance, which deteriorates heartbreakingly. In its most unsparing moments, James White is almost a fictional analogue to Allan King’s documentary Dying at Grace, which refuses to blink in its examination of the isolation of death.

Unfortunately, almost everywhere else, the film feels decidedly generic, a carousel of misplaced masculine rage and substance abuse that Abbott performs convincingly, if not particularly compellingly. There’s only so many times one cares to watch him wake up groggily from a night of bad choices and mumble “shit” as he remembers some neglected obligation.

While a scene with an avuncular Ron Livingston hints at the stakes if James isn’t somehow able to bring a semblance of order to his life, the film’s live-in-the-moment approach saps its staying power, a fact underlined by Mond’s unwillingness to even attempt an ending.