House II is one of the few movies I can remember seeing ads for on TV when I was watching cartoons in the afternoon. The ad would come on again and again, and it looked like everything I could want in a movie – monsters, human sacrifice, John Ratzenberger. However, it was also a horror movie (kind of) so no one in my family would take me to see it in the theater. When I eventually got to see it on VHS it didn’t become a favorite, but there was so much strange content in there, so many weird little elements that they stuck with me even when the movie as a whole faded away (I think I was hoping for more real horror, and not cute little puppet animals.)

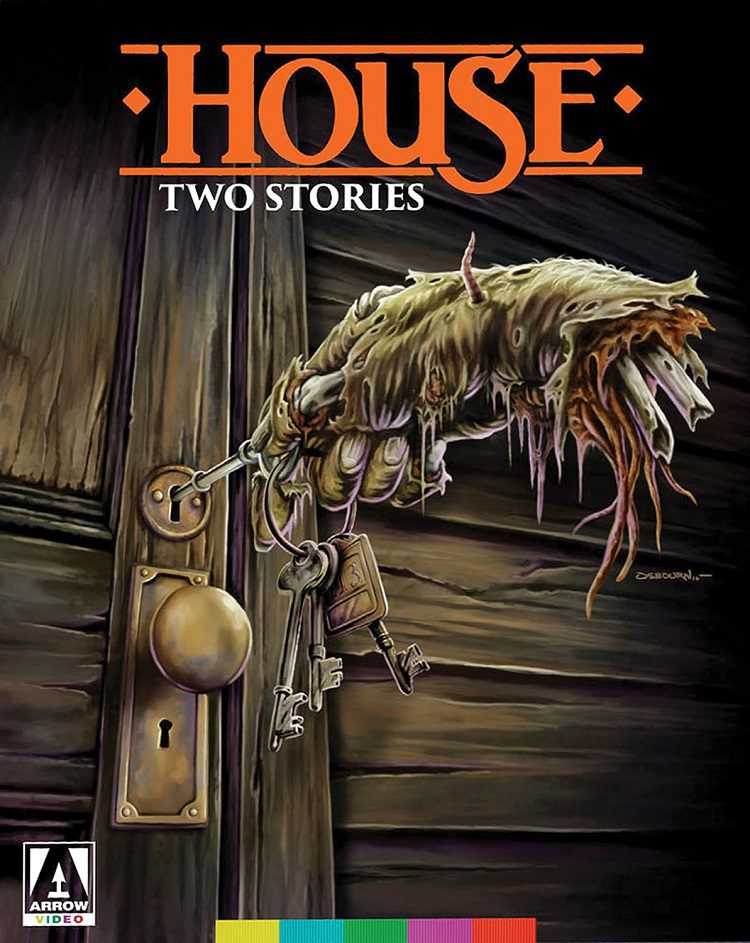

The ghost cowboy at the end made a particular impression on me, especially the skeletal horse he rode in on. And if there’s nothing more to be said for the two House movies included in this packed-to-the gills box set, House: Two Stories, they both have a go-for-broke attitude in the make-up and special effects. They go out of their way to show you something weird, even if it isn’t gross enough for the gore-hounds, and the limited budget is pretty evident in every rubbery monster.

House, the original film, was a more straightforward horror film than its wackier follow-up. Starring Greatest American Hero Bill Katt, from an age where men could have curly hair and not have to be the comic lead, he plays Roger Cobb, a Stephen King like horror novelist with a tragic past who is stuck writing a follow-up to his hit book Blood Dance. He wants to craft a memoir about his harrowing tour in Vietnam, but he can’t work and his growing isolation from his ex-wife isn’t helping. When his aunt dies, he inherits her house, which happens to be both the place where he grew up and the house from which his son disappeared, never to be found. This house is carrying a lot of baggage, and would seem to be the worst place to go break your writer’s block in peace and solitude.

Once ensconced in the house, which is decorated by his aunt’s creepy surrealist artwork, Roger begins to see things, starting with visions from his past and culminating in the terrifying demon which bursts out of the closet, a nightmare vision made up of faces that look melted in napalm.

While he’s seeking solitude, he just happens to have his “number one fan” living next door, Harold Gorton, played by George Wendt. It’s in the dynamic between these characters that House finds most of its heart. When Roger encounters the ghosts in the house, rather than get out (the sensible thing) or ignore them (the regular movie thing) he begins to try and document them, with elaborate camera set-ups while wearing protective gear (including his old military garb.) He and Harold talk about what he’s seen, and Harold seems amenable, but as soon as possible steals Roger’s address book and calls his ex-wife to tell her he’s gone nuts. It’s human touches like this that make House a more relatable film than its paint by numbers horror contemporaries.

It isn’t particularly scary, though. In a way, despite the R rating, it is kind of a kid’s horror movie, with very limited gore and the horrible things not being all that terrible, despite being directed by Friday the 13th originator Steve Miner. It is also, for my taste, simply overlit for almost every scary scene. Thing don’t pop out of the shadows, they’re seen there in full on bright light, even at night. Sometimes it works, sometimes it just exposes the limitations of the special effects budget.

Even more limited but making better use of its meager production budget is the sequel, fittingly called House II: The Second Story. A completely unrelated story from first film, despite being written (and this time directed) by that film’s writer, Ethan Wiley, House II‘s hero is Jesse McLaughlin, who is reopening a house that has belonged to his family for generations. It is built like some kind of Aztec temple, and includes a cradle over the fireplace that is, mysteriously, empty.

What’s supposed to go there is a Crystal Skull once discovered in an Aztec tomb by Jesse’s grandfather. It grants the owner eternal life, so Jesse and his friend Charlie do the only thing that makes sense: find the old man’s grave and dig him up. Where, of course, they find him alive and kicking, if a little worse for the wear, having turned into a dried up old zombie.

Gramps has the crystal skull, and needs to keep it to stay alive, but its power draws other beings near to it, and opens up doors to other worlds where these seekers can come and try to collect the skull for themselves. Unfortunately, Charlie is also throwing a kick-ass costume party (this being the ’80s) so they don’t see the muscle bound caveman warrior coming for the skull until it is too late. That’s just the beginning of the adventures that go to prehistory jungles, into South American sacrifice taking place just inside the walls of the house (this is where John Ratzenberger, electrician and adventurer, comes in handy) and culminates in a return to the old west with Gramps long lost partner and rival, Slim Reeser.

If it sounds barely coherent, that’s part of the film’s charm. There’s some character moments (Jesse’s girlfriend isn’t that into him but is possessive, Gramps is the only family Jesse has ever really known) that keeps it from being emotionally barren, but Wiley’s House II is the sort of screenplay that could be accurately described as “one damn thing after another.” Oddly, though it barely attempts anything really horrific, I found the tense and suspenseful scenes in House II more effective and atmospheric than the more numerous ones in House, which I attribute again primarily to the lighting. I have no sensible way to account for this since they were both shot by horror veteran Mac Ahlberg, who also shot Re-Animator, Ghoulies, and, according to IMDB, a heap of Swedish pornography in the ’70s.

My preference for the second House could also be familiarity. I hadn’t seen the first House (so as I remember) ever, while the second one I’ve seen at least once before, and plenty of things stuck with me. It may be that the appeal of the House series is primarily as a nostalgia vehicle for older viewers, since it’s hard for me to think of someone stumbling on this and, without a preconceived notion sticking with it. It’s enjoyable, but I can’t help feeling I liked it because I knew what I was in for. Sometimes you watch something you liked as a kid, and have new insights into it, find new qualities. Sometimes you watch it, and wonder were you thinking? And some movies you enjoyed in childhood, you can look back on and see, “Yes, as a kid I would have enjoyed this just the right way.” The House movies fit that third category.

But whatever my mixed (though positive) feelings about the movies, someone out there must love them because Arrow’s box set has a lavish set of extras. First, there’s the 148-page hardbound book, with essays about the making of all four House movies. Yes, four, though House III (released in the U.S. at The Horror Show) and House IV are not included in this box set, likely for rights reasons. On the Blu-rays themselves, each movie has a full-length commentary detailing the production, an hour long documentary, and vintages extras, including contemporary making of featurettes and trailers and TV-spots.