Written by Tim Gebhart

Imagine the conundrum. America recently entered World War II, a war the government pronounces a battle between the “free world” and a “slave world.” Less than four years before, the first page of the first story about the now nationally popular Superman called him the “champion of the oppressed.” He’s since displayed not only invulnerability but superpowers that could make quick work of the Axis. How can Superman morally allow the war to continue?

The problem facing Superman’s creators, writers, and artists wasn’t just an internal one. TIME magazine wrote about “Superman’s Dilemma” in its April 13, 1942, issue. It said that while the “mightiest, fightingest American” could end the war in “a wink,” in reality the war wouldn’t end soon. “On the other hand,” it observed, “he can’t afford to lose the respect of millions by failing to do his bit or by letting the war drag on.” The solution? Clark Kent tries to enlist in the Army in 1941 but inadvertently uses his x-ray vision during the eye exam, reads a chart in an adjoining room and is rejected because he’s “blind as a bat.”

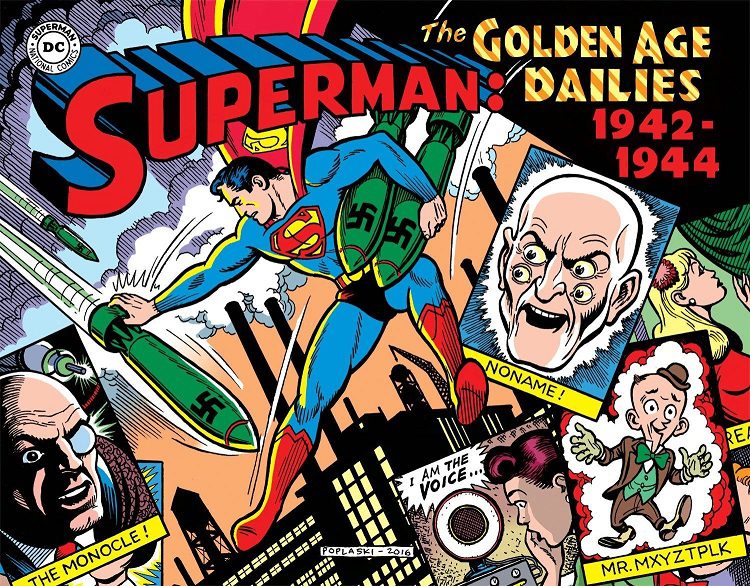

That is the kick off to Superman: The Golden Age Newspaper Dailies (1942-1944), the latest Superman release in IDW Publishing’s The Library of American Comics. The book contains more than 800 daily newspaper comic strips collected for the first time since their original publication between Feb. 16, 1942, and October 28, 1944. The black and white strips make up 11 Superman “episodes” but, surprisingly, those beginning in November 1943 don’t involve the superhero’s war activities.

The writers knew the eye test, which appeared only in the daily strips and no comic books, couldn’t alone justify Superman not intervening in Europe and Asia. They also crafted an explanation aimed at bolstering the home front patriotism. Superman tells a joint session of Congress that America’s armed forces are powerful enough to “smash” the Axis without his help. He believes his time is better spent on the home front, battling “the hidden maggots” who seek to sabotage the country’s war production. That way he can also be alert for “the old totalitarian trick of creating disunity by spreading race hatreds.” Ironically, this particular strip was published less than three weeks after President Franklin Roosevelt’s executive order authorizing the forced relocation and incarceration of Japanese Americans.

As a home-front warrior, Superman confronts — and defeats — a variety of Axis spies and saboteurs. The Leer, while Japanese, is the “Axis sabotage supervisor” in the U.S. His brother, the Sneer, will later head up Japanese sabotage efforts and the Nazis will use The Monocle, Noname, The Voice, and an elderly couple. The only time Superman ventures into enemy territory is a pre-Christmas 1942 episode in which Santa Claus is kidnapped by the Nazis and Superman goes to Berlin to rescue him from the vile trio of Hitler, Mussolini, and Tojo.

When Superman addresses the joint session of Congress, he’s introduced as “a typical, clean-cut American.” He is sufficiently representative of America at the time that the copyright page has a publisher’s note acknowledging the strips “include racial stereotypes” and are reproduced “with the understanding that they reflect a bygone era.” Not only are both Japanese and German agents caricatures, Superman refers to a “slap-happy Jappy” and two Japanese agents say Superman makes “Jap-boys velly unhappy.”

The latter comment comes in an episode that opens with Clark and Lois Lane visiting a “typical Jap relocation camp.” In the first strip, Clark pronounces the camp a “more than reasonable set-up” and their military guide says the government has done everything but “lean over backwards in its desire to be humane and fair.” Of course, the only Japanese we see in the camp are those plotting a breakout to join the Sneer’s saboteurs. Still, after Superman disrupts the ring and transfers war materials to defeat a surprise Japanese attack in the South Pacific, he closes the episode by telling readers that “most Japanese-Americans are loyal citizens.”

All episodes remain true to standard devices. Superman must continually rescue Lois from jams. Whether rescuing Lois or others, it frequently is not at the last second but the last millisecond. He still makes wisecracks that border on corny. At the same time, the war-related strips allow him greater opportunities to tout the the superiority of American values compared to the Axis.

For example, when a saboteur fails, the ringleaders inevitably kill them. In one instance, he rescues three saboteurs from that fate so they can stand trial (although their trial and execution take only a couple days). Similarly, Superman rescues three Frenchmen facing a Nazi firing squad for refusing “the honored privilege of slaving for our war machine.” And when a group of saboteurs plans on shooting Lois and two friends, one remarks that it reminds him of “the great fun I had while guarding prisoners in a concentration camp.”

In this and more subtle ways, the daily strips bolstered the country’s propaganda efforts. Yet they abandoned the war theme war before the end of 1943, although it would continue in the Sunday newspaper strips. The last episodes in the collection are far different. One introduced readers to Little Susie, Lois’ fibbing niece who figuratively and literally dreams of ways to expose Clark as Superman. Mr. Mxyzztplk, the imp from another dimension, also makes his first appearance (although the spelling of his name would later change) and Jimmy Olsen appears as a copyboy much different from character than readers would come to know in the ensuing decades.

Two main reasons led to the disappearance of Superman’s home front efforts, according to comic book historian John Wells’ excellent introduction to the book. He says lighter topics recognized that readers were weary of war news. After all, by the time Superman moved on to Fibbing Little Susie, the U.S. had sustained some 98,000 battle casualties, including more than 34,000 deaths. At the same time, just as Superman’s war efforts couldn’t negate reality, the writers and illustrators didn’t want him defined by the war. Like America, Superman needed a return to normality.

Like many of the books in The Library of American Comics, Superman: The Golden Age Newspaper Dailies (1942-1944) captures a unique slice of American history. As for Superman, this period is among the more fascinating. Although “truth, justice, and the American way” comes during this period from the Superman radio serials, the daily newspaper strips reflect our perception of those values on a far more global scale. It was a time when “champion of the oppressed” took on a whole new meaning.