More than a little melodramatic in places, Eran Riklis’ Zaytoun is a tale of unexpected friendship in seemingly impossible circumstances. The Israeli director teams with The King’s Speech producer Gareth Unwin and producer Fred Ritzenberg to craft this piece, with the Nader Rizq screenplay going through a number of rewrites on its way to primetime.

The retooling of the script was allegedly designed to take out the more “dogmatic” aspects and that’s really what Zaytoun has as both its greatest strength and greatest weakness. While the relative neutrality of the film’s politics create ample space for the friendship between protagonists, the historical atmosphere is too charged to be treated so lightly.

In Lebanon in 1982, young Palestinian refugee Fahed (Abdallah El Akal) lives with his father and grandfather. The Lebanese are going through their own civil war and find themselves in the path of Israel, so they don’t take too kindly to any Palestinians nosing around. One night, Fahed’s father is murdered in a bombing attack.

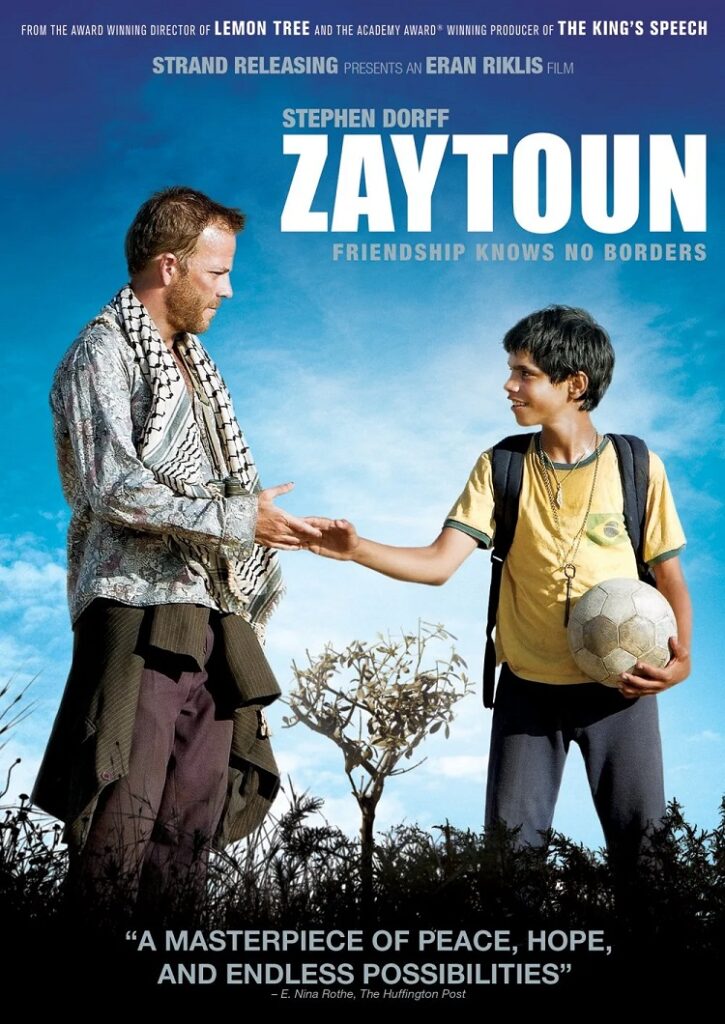

Shortly after, an Israeli pilot named Yoni (Stephen Dorff) is shot down and winds up a prisoner of Fahed’s refugee camp. An unlikely relationship develops between the two “enemies,” with the youngster relying on the aviator to take him to the land of his ancestors so he can plant his father’s beloved olive tree.

Riklis doesn’t entirely neglect the political atmosphere, but the film is mostly positioned through the eyes of Fahed. This allows the audience to view the action through his justifiable anger and reasonable confusion. He is caught in a conflict he can’t possibly understand, yet he is passionate and strikingly fierce.

Yoni, after literally dropping out of the sky, is not as zealous. When he and Fahed bond later in the picture, he describes flying short missions and getting to go home. With the youngster doubtlessly thinking about his shattered home and deceased father, this offhand approach has to be confounding.

But that’s where the essence of these characters lies. The differences between them are political, even if inadvertently so, and the fallout is personal. The cycles of hostility and reprisal provide little more than ash for small hands to sift through, but Zaytoun regrettably proposes something less controversial.

While there are some needless diversions, like Aboudi (Loai Noufi), most of Riklis’ picture attempts to get to its feathery point. Some scenes are corny in their presentation of friendship in any circumstance, but there’s little wrong with Zaytoun‘s intentions and it’s hard to doubt this movie’s heart.

At the same time, it’s hard not to hope for more. It could be argued that this story could take place between any two improbable comrades, but Zaytoun takes place in the midst of the Israeli/Palestinian conflict. There are clear political costs to explore. The choice to take out the trickier content is comprehensible, but it also keeps things too innocuous.

As a result, Riklis’ movie is decent but not as good as it could’ve been with more gas in the tank. It’s a buddy flick and a road flick, an average yarn with a commendable purpose and a remarkably light touch.