Yakuza Law is not even in the top-five craziest movies made by Teruo Ishii, and in it, a man rips out his own eyeball and throws it as his former boss, a thief is tortured by being dragged on the road by a helicopter, and a Yakuza is punished by his friends for stealing is tied to a tree, urinated on, and practically eaten alive by mosquitos. These are just a small sampling of the various horrible goings on in this anthology of short Yakuza stories, each about how the crime syndicates employ their own seedy form of justice.

Teruo Ishii, though many of his films are far from typical, had something of a typical career in the Japanese film industry in the ’60s. For most of the decade, he was making standard genre pictures for Toei. His biggest series for the decade was the Abashiri Bangaichi series of prison movies, which he made 11 of throughout the mid ’60s. As hard times fell on the Japanese movie industry, primarily pressure from the growing TV audience, the studios were pressured to make the kinds of things one couldn’t see on TV – sex and violence became the watchwords, and directors were often given great creative freedom as long as the requisite blood and nudity was on the screen.

Yakuza Law, made in 1969, is part of a series of anthology films by Ishii that involve torture, though according to the helpful historical essay in the booklet included with this Arrow Blu-ray release of the film, it was atypical of the other eight films (made all in the span of two years) in the loose series in that the objects of the torture were largely men, and there isn’t much of eros intertwined with the brutality in this film. There’s a little nudity here and there, but the connecting theme behind these otherwise unconnected stories is about the primary laws the Yakuza use to govern their own.

It’s a very loose connection, and the romanticized view of the Yakuza typical of these films is undermined when these centrally important rules are completely different from story to story. The first is set in the Samurai past, prior to the Meiji Era which saw the modernization of Japan. In this story, a conniving, cowardly Yakuza lies and steal his way into the bosses favor, and sets to undermine a rival by accusing him of theft, and trying to run off with a girl whom the boss fancies which he demonstrated by raping her. There’s extremely bloody sword-fighting, limb-chopping, and the aforementioned eye-gouging in this episode, which has Bunta Sugawara of Battles Without Honor and Humanity fame playing a yakuza with a deep sense of honor that gets him into trouble with the more duplicitous members of the gang.

The second story is less bloody (but that’s a matter of degree – in the first few minutes a man does chop off another man’s arm) and adheres pretty closely to the Yakuza clichés of the one honorable gangster who fights against his whole clan because they haven’t followed the rules of brotherhood closely enough. Minoru Oki (who was in several of the Lone Wolf and Cub movies) is Shuji, the true Yakuza, who follows an ambitious brother’s instructions to kill another Yakuza boss, and ends up betrayed: exiled from Eastern Japan, and eventually thrown in prison. He comes back after his prison stay to find his woman in the arms of Amamiya, one of the guards of the man he killed. Amamiya tries to kill Shuji the second he gets out of prison, which earns his respect, and Shuji eventually faces off against all of his former brothers in a bloody showdown. Set in what’s apparently the early 20th century, it’s still all knife fights and bloody torture.

The final, and longest of the three stories is set in (then) contemporary Japan. It has the most elaborate (and least coherent) story, involving stolen gold, succession within a Yakuza family via murder, and an assassin who is set up for a murder he didn’t commit. This story has an astonishing scene of torture where a gold thief is dangled from a helicopter by a rope, dragged along the beach, occasionally bashing into heavy objects and the like until an assassin takes pity on him and shoots the rope loose from the copter, sending him to the briny deeps. Later, a villain hiding in the backseat of a car is taken to a car crusher, where the car is smashed into a cube and he pops like a balloon filled with red paint. It’s something to see.

For fans of gore and grotesquerie, the appeal of this kind of movie is obvious. For the foreign-film aficionado, it’s a much harder sell. The stories themselves aren’t much different from the kind of fair one can see in the typical ’60s Japanese actioner: fairly simple crime stories of betrayal and honor among thieves. Those can often be violent and bloody, but Yakuza Law takes the gore to extremes that push far past realism. The opening title sequence includes a montage of torture and mayhem that is almost hypnotic in its bizarre cruelty. Men being roasted alive on spits, or dunked into rivers (also, weirdly, on a spit) or, in the more contemporary scenes being practically split in two while being lifted up by an earth mover, with gallons of bright red blood shouting out from open body cavities. Interestingly, none of these tortures actually take place in the stories of the film itself.

Part of the interest is the simple, “Oh, my God. I can’t believe what I’m seeing” factor. The effects are crude (the film is a low-budget movie from the ’60s, after all) but enthusiastically pursued, so they still have impact. And otherwise the film is beautifully made, with interesting compositions and great costuming. Yakuza Law is by no means a great film, and Ishii has made films that are crazier, like Horrors of Malformed Men, or better strange Yakuza stories like Blind Woman’s Curse. But it is a pretty cool weird cult film, and fun time for the open minded and strong stomached.

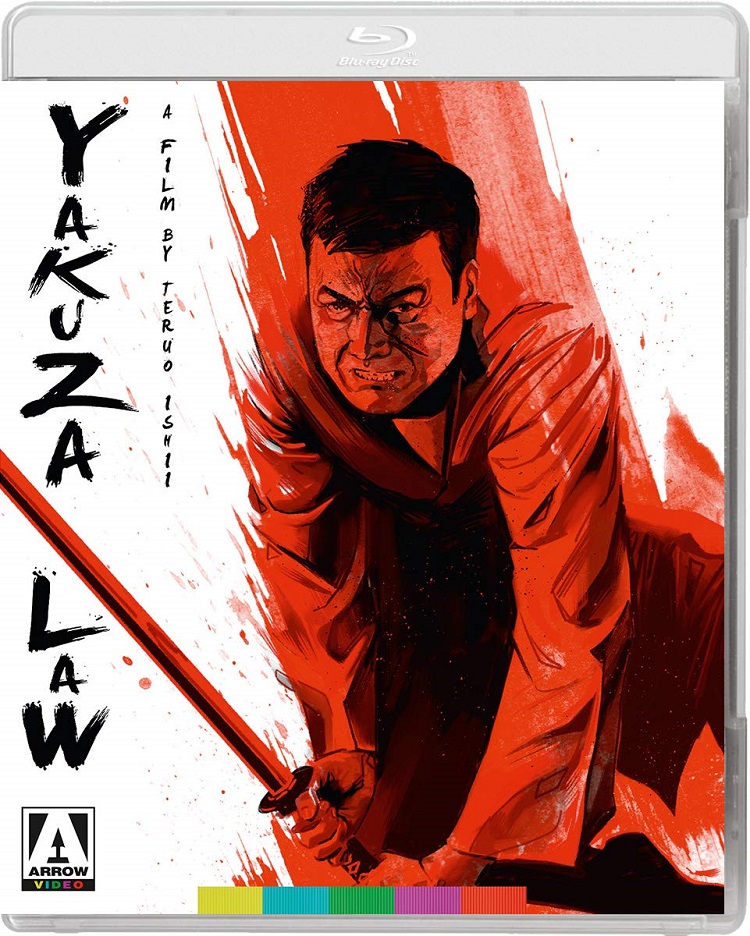

Yakuza Law has been released on Blu-ray by Arrow Video. Extras include a 48-minute long interview with the director, “Erotic-Grotesque and Genre Hopping: Teruo Ishii Speaks”, (an archival interview, since Teruo Ishii died in 2005) where he discusses his entire long and varied career. There’s also a feature-length commentary track by Japanese cinema expert Jasper Sharp, where he discusses the histories of the director and the film voluminous cast. There’s also a historical essay in the accompanying booklet by Tom Mes.