What if everything you thought you knew was nothing but a fabrication? This is but one of the many themes in the newly restored Rainer Werner Fassbinder film World On A Wire. As the protagonist of the film, Fred Stiller (Klaus Lowitsch) puts it: “I can’t be alone in thinking nothing really exists. For Plato, reality exists in the realm of ideas. And Aristotle conceived of matter as passive non-substance that only becomes reality by thought.”

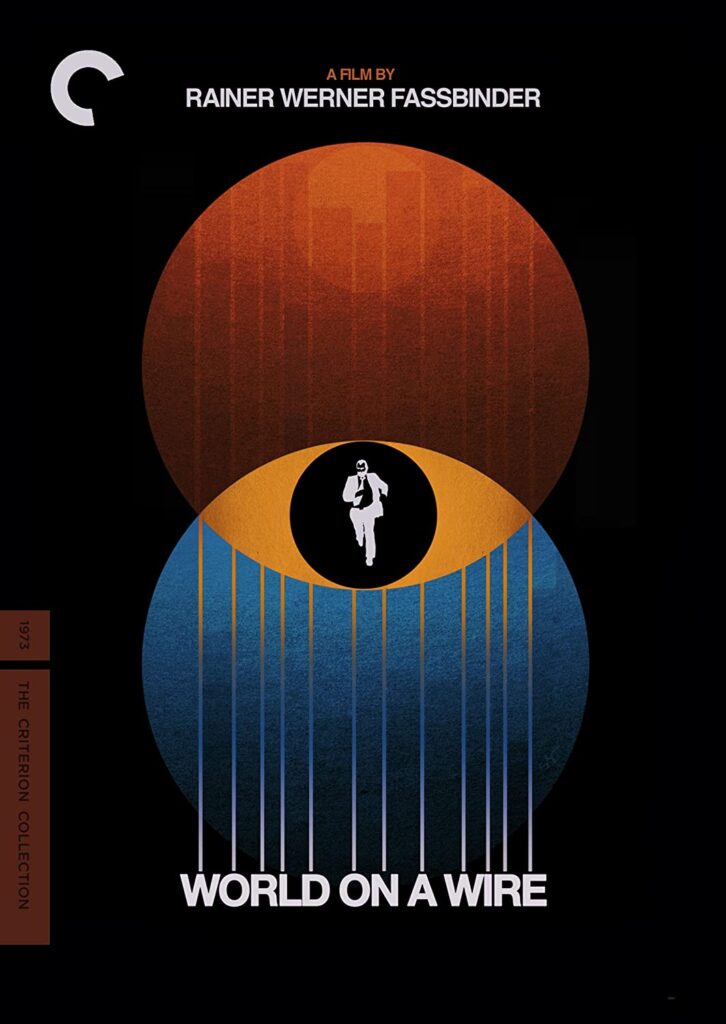

I will begin by stating the obvious – this two-DVD Criterion Collection edition is a must for Fassbinder fans. It is certainly one of the most obscure works in his career. For one thing, it is his only venture into the realm of science fiction. Then there is the hard-to-believe fact that the 212-minute World On A Wire was originally aired as a two-part German television special. Besides that initial presentation, it had only been shown theatrically a few times. In 2010, the Rainer Werner Fassbinder Foundation digitally restored it. This set marks its first appearance on Region 1 DVD.

But the film’s appeal goes far deeper than simply being an obscure Fassbinder work. The story, and the way Fassbinder filmed it does not look or feel in any way like something one would expect from a TV movie. World On A Wire was adapted from the 1964 book Simulacron-3 by the American author Daniel F. Galouye. Although it is not a particularly lengthy novel, the scenes are so vivid that early on it was decided that it could not be properly reproduced in the original 90-minute incarnation which they had pitched to the network. In one of the extras, co-screenwriter Fritz Muller-Scherz explains that Fassbinder had to go back to the network and secure their approval to basically double the scope of the project. Quite a task, but he succeeded. Not only that, but he was able to secure funding for an unprecedented six weekends of on-location filming in Paris.

Only a Parisian would know those scenes though. The idea was to film in a locale that looked futuristic, say 20 years ahead in time or so. As it turned out, there was so much new construction going on in Paris at the time that it worked perfectly. This approach reminds me a great deal of the way the producers of Conquest of the Planet of the Apes (1972) dealt with a similar situation. In that case, they filmed in the then newly built Century City, and it looked weirdly futuristic enough for their intentions, and helped keep the budget in line.

The basis of World On A Wire is the relationship between politics, business, and lobbyists. To anticipate the wants and needs of society 20 years out, a government funded experiment is initiated. Rather than simply using computer models to conduct the research, an actual “world” is created, populated with what we would now call androids. Only one of them knows the truth, and he is named Einstein. Einstein functions as the contact between the real world and the simulation.

One of the factors that make this movie so compelling is Fassbinder’s wonderful inventiveness. Mirrors were a staple of his work, but I do not know whether anybody has ever used them as effectively as he does here. We are constantly wondering if the world Fred Stiller lives in is real or the simulation. From the very beginning there is a feeling of paranoia as the original head of the project, Professor Henry Vollmer (Adrian Hoven), mysteriously dies. Stiller is convinced Vollmer was murdered, because he knew too much. Stiller finds himself promoted to lead the task, and not only wonders what really happened with Vollmer, but whether he too will be killed when he finds out the true nature of the experiment.

To create this virtual reality, the scientists programmed versions of themselves and others to live in it. So there is the constant question of whether we are watching the real world or the simulation. Just to maintain this type of tension for three and a half hours is quite a feat in itself. There are layers upon layers of intrigue, and right up until the end we are kept in the dark as to the “reality” of the occurrences.

Fassbinder throws in some great flourishes as well. The nightclub that Stiller and his co-workers frequent features a Marlene Dietrich look-alike and is supremely decadent. Then there are the “visits” from the real world (called “above”) to the simulation (called “below”). One never knows which one is which, and Stiller gets the distinct impression that he is actually living below.

Then there are the characters themselves. All of them are almost alien – mysterious and downright weird. Some things they do make perfect sense, others are baffling. Again, this keeps the viewer on edge, as from moment to moment you never know what is going to happen.

Two comparisons are impossible to ignore. The first is Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (1971). While the storyline is quite different, the settings of the near-future are very similar, as is the strange behavior exhibited by basically everybody. I found the works of Philip K. Dick to be even closer to what World On A Wire is all about. Two very famous and influential adaptations of his novels are Blade Runner (1982) and Total Recall (1990). Those are the proverbial tip of the iceberg though. He was a brilliant writer, and almost everything he authored dealt with similar subjects.

The opportunity that Fassbinder was given to really stretch out the philosophical implications in three and a half hours was utilized to an unprecedented degree. The tension never leaves. Even as the credits roll, one still wonders if Stiller is in a “glass bubble.” You may question whether he ever even existed at all. The way Fassbinder presents it, it could be reality – or it could be simply a dream ala Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz (1939). The possibility exists that it all could have been an android’s dream. Depending on how you look at it, there may or may not be any final closure.

As previously mentioned, there are deep concerns explored in World On A Wire. With the very reason for the creation of a completely artificial environment for United Steel Inc. to project their business model and society’s attitudes some 20 years in the future, the book and film were brilliantly prescient. Look no further than at what Google is doing today as an example of tracking people’s behavior. Fassbinder even assumed cameras on every corner, which is becoming more and more a reality.

As a part of the post-war German generation, Fassbinder pulls no punches. His satires of Dietrich and the Nazis are not guarded at all. You do not have to look very closely to see his disgust in what came before him. World On A Wire is an absolutely fascinating piece of work, and this Criterion Collection edition presents a splendid restoration of it.

There are two rather well-done extras included. The first is a 33-minute interview with Fassbinder scholar Gerd Gemunden, who discusses the film and its place in Fassbinder’s full body of work. It is a matter of simple math to deduce this, but the fact that Fassbinder was only 28 years old when he directed World On A Wire still floors me. He was already a master.

Even better is the 50-minute documentary Fassbinder’s ”World On A Wire”: Looking Ahead to Today. This features interviews with cinematographer Michael Ballhaus, co-screenwriter Fritz Muller-Scherz, and actor Karl-Heinz Vosgerau. Their combined insights into the methods and motivations of Fassbinder are fascinating, as is the whole story of how it all came together as a TV movie in the first place. There is also a very informative essay by film critic Ed Halter included in the accompanying booklet.

World On A Wire is a superb piece of science fiction, with what I consider to be a very broad appeal. Whether you are even familiar with Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s other films is not necessary. It is a great story, filled with unlikely twists and turns and very creatively filmed. The Criterion Collection two-DVD edition of World On A Wire is highly recommended.