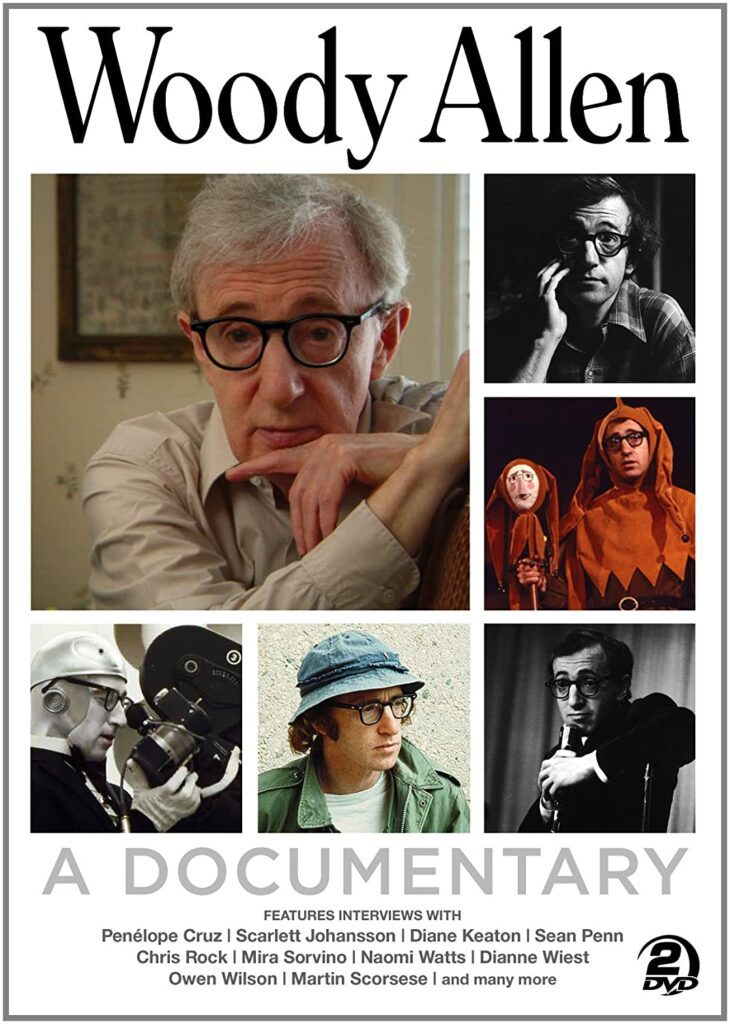

Robert B. Weide’s Woody Allen: A Documentary airs in two parts on PBS’ American Masters and is a comprehensive biography about a man who has had one of the most impressive careers in all of show business.

Weide interviews actors who have worked with Woody in all stages of his film career, from Louise Lasser and Diane Keaton to Scarlet Johansson and Owen Wilson. The viewer also hears from those who have worked with Woody behind the camera, such as writers Mickey Rose and Marshall Brickman, cinematographer Gordon Willis, and agent/producer Jack Rollins. A few notable fans, Martin Scorsese and Chris Rock to name two, also offer their thoughts. The main highlight of the documentary is Weide getting Woody to sit down to reflect on his life and work. Weide edits in pieces of Woody’s films to show how his life has influenced his art.

Along with his sister Lety Aronson, who has also served as his producer since 2001’s Small Time Crooks, Woody discusses the history of their parents, who appear in archival interviews, and their grandparents, one of whom owned a movie theatre, the source of Woody’s infatuation with the medium.

Woody’s sense of humor opened doors for him. He started submitting gags to newspapers. He then got a job writing for comic Mike Merrick. From there he wrote for radio programs, did sketch work in the Poconos, and joined The Sid Caesar Show. His agents Jack Rollins and Charles H. Joffe pushed him into doing stand-up comedy, and he performed on many shows, as seen in clips of Woody appearing on What’s My Line?, The Steve Allen Show, and The Ed Sullivan Show.

As they always do with someone talented, Hollywood came calling. His first job was the screenplay for What’s New, Pussycat? in which he wrote himself a role. Woody didn’t care for how the studio tampered with the film, so he made sure he directed Take the Money and Run, and the rest, as Weide shows, is history.

Like all great artists, Woody wanted to expand his palette. No longer content with just being funny, he took his first step in a new direction with Annie Hall, a major triumph. Here, he began his working relationship with Willis, resulting in his films having a more sophisticated look. Woody’s successes allowed him to make whatever he wanted, which he did with the serious family drama Interiors, which showed an influence from Ingmar Bergman’s work. Woody then made his masterpiece, Manhattan, which naturally he didn’t like. Part One concludes with Stardust Memories, influenced by another great European director, Federico Fellini, and specifically 8 ½. The film failed with both the press and audience at the time.

The shorter Part Two opens up with a brief look at Woody’s recent career rejuvenation of films shot in foreign locations. The filmography continues with another Bergman-influenced film, A Midsummer Night’s Sex Comedy, the first of many featuring Mia Farrow. After Hannah and Her Sisters, Weide unfortunately starts to skip over pictures, particularly the ones of the beginning of the millennium, considered a weak period. It’s unfortunate because Woody’s reaction to the presumed misfires and what, if anything, he took from the results would have been illuminated how he works.

Weide briefly covers the break up with Farrow and their child custody issues, which he had to considering how public the matters were. Its absence would have drawn more attention. Woody, demonstrating a lack of self-awareness to his own celebrity and a lack of understanding of how the gossip industry works, seems genuinely surprised the tabloids covered it all.

The documentary shows behind-the-scenes footage of Woody on the set of Sleeper with Keaton and working with Naomi Watts and Josh Brolin on You Will Meet a Tall Dark Stranger and will have fans wishing for more material in this vein. I would love to see Woody on the set of Manhattan, working to create the look of Zelig, or editing any of his films.

Towards the end, Woody is resigned to the fact that his limited successes have allowed him to keep making movies, which he is happy with, but he has no faith the results will ever be different. Weide concludes with the revelation that Woody’s latest release, Midnight in Paris, is his most financially successful, a testament to the continual performing of one’s craft.

Woody Allen: A Documentary offers some fresh material and insight to those like myself who have already read biographies and film criticisms about him and his work. Weide could have delved deeper into Allen’s processes as an artist and explored his reaction to the reaction towards his films, but then Allen, who is always working on the next project, likely never offered that information. This epic is a fitting tribute and will surely delight fans.