Though many roads were constructed during the European western era of the ’60s, very few paths were created that lead to fame for stardom-starved individuals on either side of the camera. And those went down such lonely, rugged trails dared not tread lightly. Providing fate was on your side, you could find yourself walking in the footsteps of Clint Eastwood – who was little more than a television actor appearing in a weekly western show before Sergio Leone opened the door to international acclaim for him. If lady luck was not guiding you along the way, however, there was the possibility that something hideously and hilariously awful may happen to you during your travels.

Such a cruel twist of fate occurred in the late ’60s when, as the entire Euro-western craze began to wane, people other than the Italians (who essentially pioneered the sub-genre) were eagerly playing their hands despite the fact that the entire game had changed. During the beginning of 1967, William Shatner, another American television actor who was taking a break from his weekly series, something called Star Trek – which was basically a western set in outer space – travelled to Spain to engage in a short film shoot for a small group of largely unknown filmmakers. But instead of finding the same success the effectively lowkey Mr. Eastwood enjoyed by remaining effectively lowkey, Shatner’s big shot at becoming a cinematic big shot ultimately failed because he just remained Shatner.

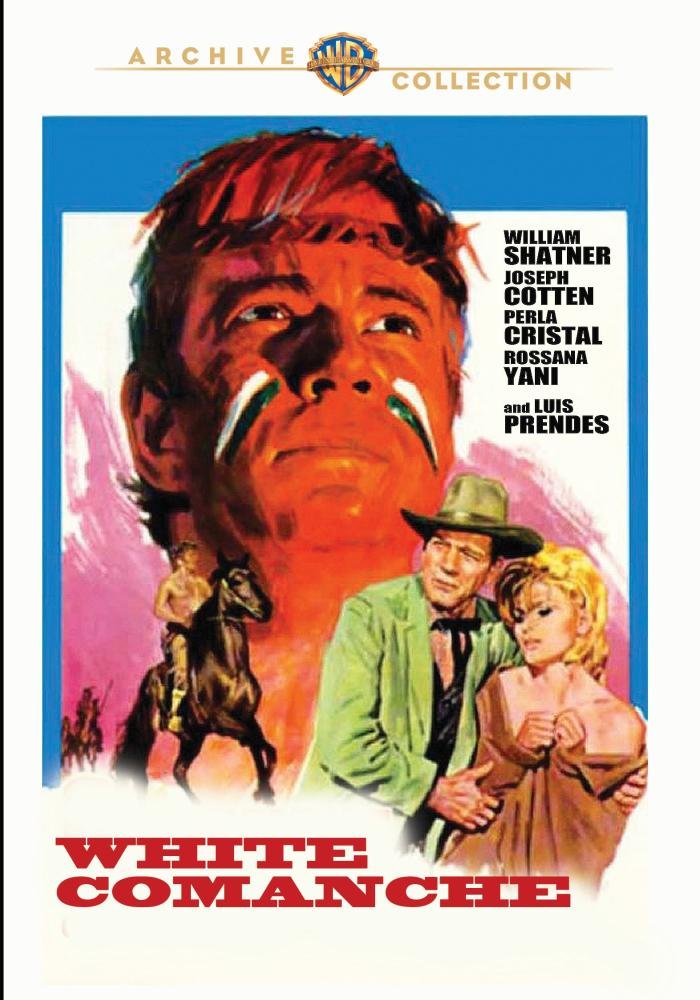

In the years following its (presumably) brief release to theaters, 1968’s White Comanche has earned the rare distinction of being hailed as one of The 100 Most Enjoyably Bad Movies Ever Made in John Wilson’s The Official Razzie Movie Guide. And from the very first frame, you can immediately see why: White Comanche is an amazingly amateurish, incredibly inept production. The story, credited to pulp/western author Frank Gruber and future TV writer Robert I. Holt, was most likely brought over to Spain by one of the film’s American producers (the main credited backer is Sam White, who produced several episodes of The Outer Limits including the memorable “Cold Hands, Warm Heart” with William Shatner), if not by Shatner himself.

First off, the story stinks. While there’s no telling what the film’s Spanish crew took out or added in, the basic premise seems to have been something that was tossed out by even the big American studios during the ’50s when they were keen to make any sort of western just for the sake of it (which would lead to the genre becoming all washed up in time for the Italians to re-invent it). Here, in a tale that defies all logic, Shatner plays twin brothers – one good, the other bad – who were, in fact, born from a white father and Comanche mother. Nevermind the fact that the audience cannot discern Shatner’s sun-basked pink skin from any other Yankee’s pale pigmentation: the characters in this dud of a flick can spot his Native American ethnicity a mile away – to wit they promptly judge accordingly.

Representing the positive aspects of interracial breeding in ’60s cinema is Johnny Moon (Shatner), the loner light-eyed sibling of the eponymous villain, black-eyed Notah Moon (Shatner, again). Johnny lives in the white man’s world, though he is frequently not welcomed there. Notah, on the other hand, has spent too many moons indulging in peyote, to the point where he has practically become a cult leader to his Comanche brothers and sisters, whom he leads in various acts of violence against whitey. After a side-splitting opening, wherein the artistic limitations of the filmmakers are revealed faster than warp speed, Johnny and Notah denounce each other, and agree to engage in a final showdown to the death in the nearby town of Rio Hondo after a few days.

Johnny ventures to Rio Hondo, where he starts to form an uneasy alliance with the sheriff, brought to life by stalwart (if humiliated) talents of sparsely-used top-billed veteran actor Joseph Cotton, who is the only performer to grace the film with any dignity whatsoever. Johnny also makes a few enemies, such with the local bad guy General Garcia (Mariano Vidal Molina), who is doing his darndest to wage war with slimy saloon owner Grimes (Luis Prendes). Meanwhile, Grimes’ star showgirl, Kelly (Argentinean-born beauty Rosanna Yanni), has a few reservations [ta-dum] about the newly arrived stranger in town, as he looks exactly like the half-breed White Comanche who attacked her stagecoach at the beginning of the film and chased her down to humiliatingly ravage her like Evil Kirk in “The Enemy Within”.

Soon, the whole Notah thing is completely forgotten, giving way to an underdeveloped (or at least poorly-realized) subplot about Johnny’s own inner demons and dependency on alcohol. Cotton pops up intermittently to show Shatner a thing or two about acting, while the Garcia/Grimes tension heats up to the point where you could possibly melt a hunk of warm butter after the course of several days. Ms. Yanni – one of the movie’s many co-stars best known today for their work in Paul Naschy horror films, giallos, and other (much better) Euro westerns – shows a little skin here, though things are kept at a PG standard with her. Blood flows fairly freely, however (a lot of headshots in this one), though, the movie could be rated R for the gratuitous shots of shirtless Shat alone!

Jean Ledrut, the French composer who supplied the score to The Trial – a film helmed by Joseph Cotton’s former colleague, Orson Welles – supplies a hysterically inappropriate soundtrack here. Some of the music sounds like it was rejected from a Saul Bass title sequence. Other pieces sound like they were taken from a minimalist big band combo who had half of their musicians call in sick the day they were supposed to lay down the score for a late ’40s B-grade noir flick. Toss in various, amusing elements such as bad dubbing, grossly incompetent editing, a noticeably bad instance of deep focus, and small-time players who were undoubtedly forced to join Overactors Anonymous shortly after production wrapped (the epic knife fight between Evil Shatner’s squaw Perla Cristal and henchman Luis Rivera is an excellent example).

All this and an egotistical, narcissistic mid-original series Trek Shatner at his hammiest, too. Sure, White Comanche can’t get anything right, but you definitely can’t go wrong with entertaining trash like this! And there have been many a late-night television hound and video store bargain bin scavengers who have discovered the joys of this paella western for themselves throughout the years since Shatner unsuccessfully tried to sell the turkey to NBC when he brought the completed work back with him from his brief European vacation. (Oh, to have been a fly on the wall during that conversation!) White Comanche has popped up in cheapo collections from many budget video labels over the years, always from the same, tired, worn-out full frame print.

In fact, it threw me for a loop when I saw that the Warner Archive Collection was adding this timeless guilty pleasure to their library, as the public domain atrocity had received so many releases since the very advent of home video. But nothing could prepare me for the new widescreen presentation from the WAC, as made available via a newly-discovered source! Not only does the movie now sport some color (well, that “red-skinned” Shatner’s still a pretty pale fellow), depth and contrast (well, except for the story or its characters), but we get a bit more screen information to boot! And the newly-widened screen only adds to the deliriousness, such as during the opening stagecoach massacre, where you can see quite clearly that the coach is not moving for its interior shots.

A nice, cleaned-up English (dubbed) audio track accompanies the new print of this campy cult classic, revealing every bit of dialogue – whether it be outrageously Shatnerian or majestically soft Cotton – to the fullest. (And yes, that little boy who gets gunned down in the bizarrely-edited gunfight even though he’s nowhere near the line of fire sounds even more like the much older voice actor he was dubbed by than ever now.) No special features are included with this release (I don’t think I’ve seen a single trailer for this one anywhere, which should tell you how truly embarrassed everyone who ever handled the movie must have really been!), but the fact that we finally have a decent print for an indecently delicious and monumentally epic disaster such as this is reason enough to celebrate like Shatner at a hosted bar.