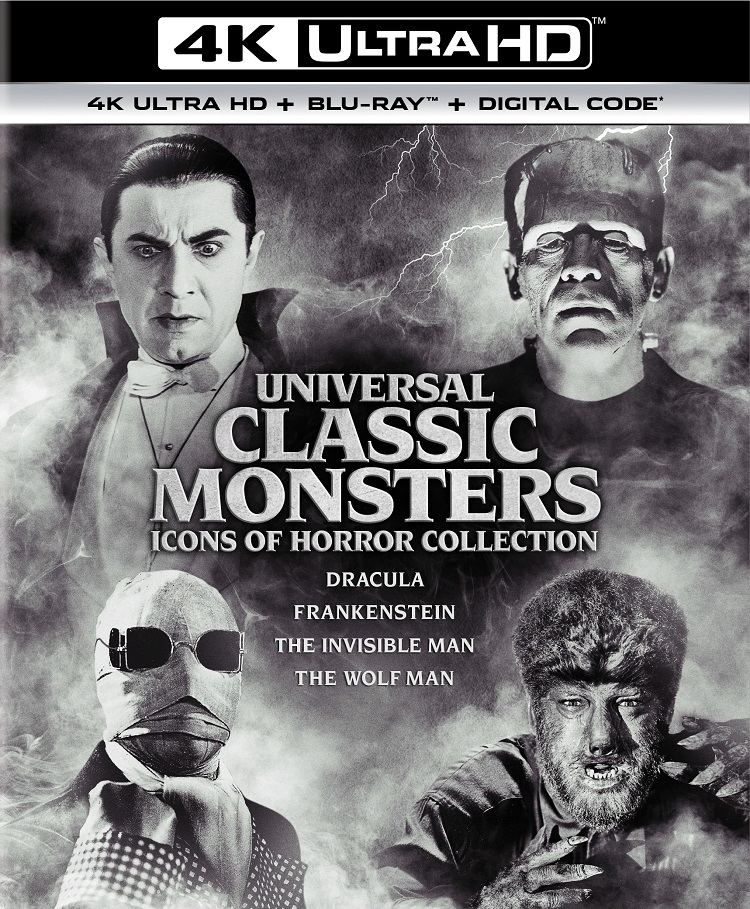

The longevity of the iconography of the Universal monster films in popular culture is truly remarkable. A single image of one of the characters featured on the cover of this collection is enough to evoke an entire genre. The looks of these monsters have become a cultural shorthand, even to those who have never gone back and watched these movies themselves.

The movies, by the way, in the Universal Classic Monsters: Icons of Horror Collection include Dracula (1931), Frankenstein (1931), The Invisible Man (1933), and The Wolf Man (1941). There was no franchise of horror films back then (and shouldn’t be, as the defunct attempt at the Dark Universe proved). Still, these movies became the foundation of the American horror film tradition. Even beyond the characters, the settings and atmospheres of these films would be the look of horror. It wasn’t until the success of independently produced Night of the Living Dead (1968) that studio American horror films began to break with the gothic trappings these movies employed.

But how are the films themselves? As with anything of this vintage, an audience is going to get out of it what they put into it. If one’s primary concern with a movie that it’s “dated”, I’d suggest another interest. But the styles and pacing of an era can take some getting used to. The limitations of technology and technique can be hard to paper over with good intent. And sometimes classics aren’t as good as they might be remembered.

Dracula was the film that opened the market up for more serious scary movies in the American studio system. Before this film, the typical studio horror movie would be half tongue in cheek, and more often than not involved someone in a gorilla suit running around a scary house. Dracula takes itself and its story seriously. For the first half hour of the film, it also succeeds marvelously.

In a loose adaptation of the novel, we follow real estate agent Renfield as he moves across the Transylvanian landscape, until he comes under the sway of Count Dracula. The Count is purchasing land in England. Once there, Dracula insinuates himself into the lives of his neighbors, especially the beautiful Mina. Her fiancée is informed by the famed scientist Van Helsing that Dracula is a vampire, and they have to work together to save Mina life, and her soul.

All of the early scenes of the film have a mesmerizing quality, with gothic imagery mixed with some surprising weirdness. The prevalence of armadillos in Dracula’s castle has always struck me as a properly off-putting element. And Bela Lugosi’s heavily-accented performance is justly celebrated. Unfortunately, the second half of the film betrays its origin as the adaptation of a stage-play. Several scenes are simply people sitting around and talking at each other. The camera is often static, and the pace moves very slowly for a relatively short film.

While Frankenstein is also based on a play adaptation of the novel, it never falls into this unfortunate trap of staginess. From the opening scene in the graveyard to the climax of the burning windmill, it contains the visual cinematic dynamism that wasn’t always common in early sound films. In many ways, it looks more like a gothic silent film, where the camera wasn’t as constrained with the physical realities of recording sound.

In this story, Henry Frankenstein is worrying his family by spending all of his time working on secret experiments in his laboratory. When the trio of his fiancée, best friend, and old professor pay him a visit, he shows them the culmination of his work: a resurrected, reconstructed corpse. But the corpse has problems, and goes on a rampage that leads to that other iconic image of Frankenstein: villagers with pitchforks and torches.

The make-up for the Frankenstein monster has been so widely caricatured that it can be difficult to see it with fresh eyes, and not as a cartoon version of itself. It is truly a masterwork of early monster movie makeup. It’s eerie and corpselike. Boris Karloff’s performance as the monster is frightening and tragic. And though it has some of the flaws of its time (the need to introduce comedic, buffoonish characters which can wreck the mood is a prevalent one), it’s a remarkably effective film.

James Whale directed Frankenstein, as well as the next film in the collection: The Invisible Man. This, based on the H.G. Wells novel, is the most special effects heavy film here, and they remain impressive, when considering the technology of the time. Sure, a modern viewer can see the strings and easily detect some of the wobbly aspects of optical compositing. But they lead to often startling images of a half-formed man.

The film stars Claude Rains (though you never see his face until the very end.) An experiment has turned him invisible, and deranged his mind. While he attempts to find a way back into the world of the visible, he antagonizes those surrounding him and eventually goes on a rampage that leads to murder. It’s the beginning of a reign of terror that he thinks will catapult him into political power. Meanwhile, all his fiancée wants is for him to come home and be cured.

The Wolf Man came nearly a decade later, and it has an appreciably more modern pace and structure than the older films, coming as they did at the birth of sound cinema. The film stars Lon Chaney Jr. whose presence I’ve read one critic uncharitably described as “bovine.” He’s an amiable actor, if not an engaging one, and he plays the part of an unwittingly cursed man ably.

He’s not that believable as Claude Rain’s aristocratic heir, whose ancestral home he has returned to after the death of his brother. He takes a local girl to a gypsy fair and is attacked there by what appears to be a large dog. Anyone who’s read the title of the film knows what really attacked him. The pace is a little poky, and the story isn’t all that soundly structured, but it’s a good-looking film. Jack Pierce’s wolf transformation sequences unfortunately can’t impress today like they did when the film was released.

All of these films were, of course, shot in black and white and all of them are quite old. Both the materials and some of the cinematographic techniques, especially of the earlier three films, can leave something to be desired. This 4K release has put all four in the best possible light. Deep blacks and shadows (which these films have plenty of) are complimented by highly detailed imagery. These are as good as these films have ever looked on home video.

It’s a shame that it’s only the four, a decision that makes plenty of sense financially (more sets released means more sets for consumers to consume). As a satisfactory collection or archive, it makes less sense. When moving the collection of Universal Monster movies to Blu-ray, there was an initial eight-film release that covered the essentials. That selection of films, which included The Mummy, Creature from the Black Lagoon, Phantom of the Opera, and perhaps the best film from the era, Bride of Frankenstein, made sense as one stop for the collector, without being too much. This four-film collection feels like a transparent withholding, kind of a cash grab.

Still, despite my misgivings about the nature of this collection, I can’t fault the content. Sure, more films would have made sense. In the extras department, there’s nothing new here that the avid collector won’t already have. But the films are the main attraction, and their presentation here is nothing short of amazing.

Universal Classic Monsters: Icons of Horror Collection has been released by Universal. The collection contains eight discs: four 4K and four Blu-ray discs with the same content. Dracula extras include a pair of commentaries, one by film scholar David Skal, and one by Dracula: Dead and Loving It screenwriter Steve Haberman; “Dracula: The Restoration” (9 min), a look at the restoration of the movie; Dracula (1931) Spanish Version (103 min), which was shot simultaneously with the Browning film; an Alternate Score Track which adds Philip Glass and the Kronos Quartet’s excellent score to the mostly music-less film; “The Road to Dracula” (35 min) a documentary about the film, and “Lugosi: The Dark Prince” (36 min), a documentary about Bela Lugosi.

Frankenstein includes a pair of commentaries, one by Rudy Behlmer, and one by Sir Christopher Frayling. Video extras include “The Frankenstein Files: How Hollywood Made a Monster” (45 min), a documentary about the film; “Karloff: The Gentle Monster” (38 min), a documentary about Karloff; “Universal Horror” (95 min), a documentary about the entire collection of Universal Horror movies; “100 Years of Universal: Restoring the Classics” ( 9 min), a short film about the restoration of the Universal horror movies; “Boo!: A Short Film” (10 min), a short parody of the film.

The Invisible Man includes an audio commentary by Rudy Behlmer. Video extras include “Now You See Him: The Invisible Man Revealed” (35 min), a documentary about the film; and “100 Years of Universal: Unforgettable Characters” (9 min), a short film about Universal’s gallery of characters.

The Wolf Man includes an audio commentary by Tom Weaver. Video extras include “Monster by Moonlight” (33 min), a documentary about the film; “Pure in Heart: The Life and Legacy of Lon Chaney, Jr.” (37 min), a documentary about its star; “He Who Made Monsters: The Art and Life of Jack Pierce,” a documentary about the film’s make-up artist; “From Ancient Curse to Modern Myth” (10 min), a short film about the movie; and “100 Years of Universal: The Lot” (9 min), a film about the Universal backlot.