Kenji Mizoguchi is considered one of the masters of Japanese cinema, striking a balance between the contemplation of Ozu and the emotion of Kurosawa, who looked up to Mizoguchi. He has been championed by the likes of filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard and New York Times critic Vincent Canby. He began in the silent era and his first acclaimed films were made in 1936 about the struggles of women, Sisters of the Gion and Osaka Elegy. Ugetsu, a masterpiece from his latter period, came out in 1953 and was the second of three consecutive films that earned him the Silver Lion from the Venice Film Festival.

Buy Ugetsu Criterion Blu-raySet during the civil wars of 16th century Japan, the film tells the story of two families torn apart by the men’s drive for success because false paths are chosen. Genjuro is a potter so obsessed with making money and the benefits in stature that will accompany it he puts lives in jeopardy to attain it. Tobei wants to impress his wife by becoming a samurai but is rejected by their ranks. He too is blinded by his desire and makes reckless decisions in the pursuit of his goal.

When a marauding army is on its way, most of the villagers flee. Genjuro and his family along with Tobei’s stay dangerously close by so Genjuro can make sure the fire in his kiln doesn’t go out, which would cause him to lose a batch of pottery. After the army storms through, the families gather up all of Genjuro’s pottery and head out to the city to sell it. As they cross the lake, they come across a small boat with a man who has recently been attacked by pirates and is near death. Genjuro has his wife and young child disembark to keep them safe. He tells them to hide in the wilderness and await his return.

At the marketplace, they make a great deal of money. Genjuro is asked to bring a large order to the home of the very beautiful Lady Wakasa. She is very impressed with him and his work, which feeds into his ego. Tobei runs off to buy the armor and weaponry that a samurai needs. He intentionally loses his wife in the crowd and pursues his ambition. After fulfilling their dreams, the men discover the havoc their choices have wreaked upon their families and themselves.

To create this powerful and thought-provoking story, Mizoguchi wisely chose talented people to bring his vision the screen. The poignancy of the characters is fully realized by the amazing performances of the cast who create natural, believable characters. Mizoguchi was very serious about the accuracy of the film’s setting, which can be attested to by the fact that a person on the crew was credited with Period Authenticity.

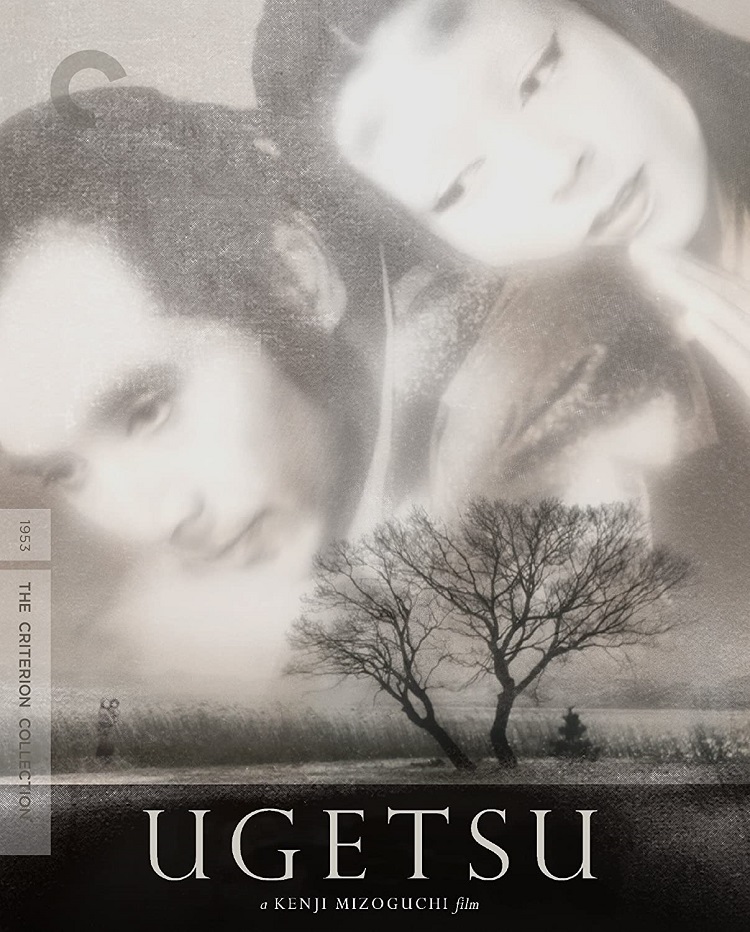

The black and white photography and the imagery of the scenes are a sumptuous feast for the eyes created by the film’s cinematographer Kazuo Miyagawa. However, the negatives must not have been cared for well over the years. There are very faint scratches that run across the entire frame throughout many parts of the movie. It creates an effect that looks like its raining. It is noticeable, but as the film progresses and captures your attention, it doesn’t rise to a level of bothersome at it would in lesser films.

Ugetsu is accompanied by The Criterion Collection’s standard high quality of bonus features, intensifying the viewing pleasure and appreciation of the film and director. A commentary track recorded by filmmaker and critic Tony Rayns provides an in-depth analysis of Mizoguchi’s artistry as well as information about the production. For example, he explains the reason for story adaptation changes and reveals creative arguments between Mizoguichi and producers.

Two of the film’s crewmembers also provide insight into the film’s creation: First Assistant Director Tokuzo Tanaka in a new interview and Miyagawa in a short interview from 1992. “Two Worlds Intertwined” is an appreciation of the film by director Mashiro Shinoda. He discusses the blending of realities in the film between the real world and the supernatural. He also speaks about the innovative use of music by the film’s composer Fumio Hayaska. The second disc features a lengthy and thorough documentary, Mizoguchi, The Life of a Film Director. The two and a half hour film was made in 1975 and examines in great detail both his life and his work.

Aside from the discs, there is a 72-page booklet that includes an essay by author Phillip Lopate as well as the short stories that inspired the film. Elements of Genjuro’s story can be found in “The House in the Thicket” and “A Serpent’s Lust” from Akinari Udea’s Tales of Moonlight and Rain. Monsieur Caillard’s ambition for a medal Guy de Maupassant’s “How He Got the Legion of Honor” parallels Tobei samurai aspirations.