In the industrial town of Seraing, Belgium, Sandra (Marion Cotillard) has been on sick leave from her manufacturing job after a nervous breakdown. In her absence, her coworkers realize they can cover her shift by collectively working slightly longer hours. Just as Sandra is ready to return to work, she finds out that the bosses have given her coworkers a choice – they can either return to their normal shifts and have Sandra come back to work, or they can continue working the longer shifts and receive a €1,000 bonus. By accepting the bonus, Sandra will no longer be employed. Overwhelmingly, the workers voted to take the bonus.

With the help of a friendly coworker, Sandra is able to convince the big boss to hold another vote, stating that her supervisor unfairly pushed her coworkers into voting against her by saying things like someone had to be laid off anyway. The new vote will be Monday morning, giving Sandra the titular time period to convince her coworkers to give up the bonus and take her back on.

Think about that for a moment. How painstakingly awful would it be to have to track down your coworkers one by one, look them in the eye, and basically beg them to make a huge sacrifice so that you can keep your job?

For the bulk of the film, this is what we watch – Sandra travels across town and back again, knocking on doors, pleading her case, and listening to the sob stories of her coworkers as they reason out why they too are desperate for the extra cash.

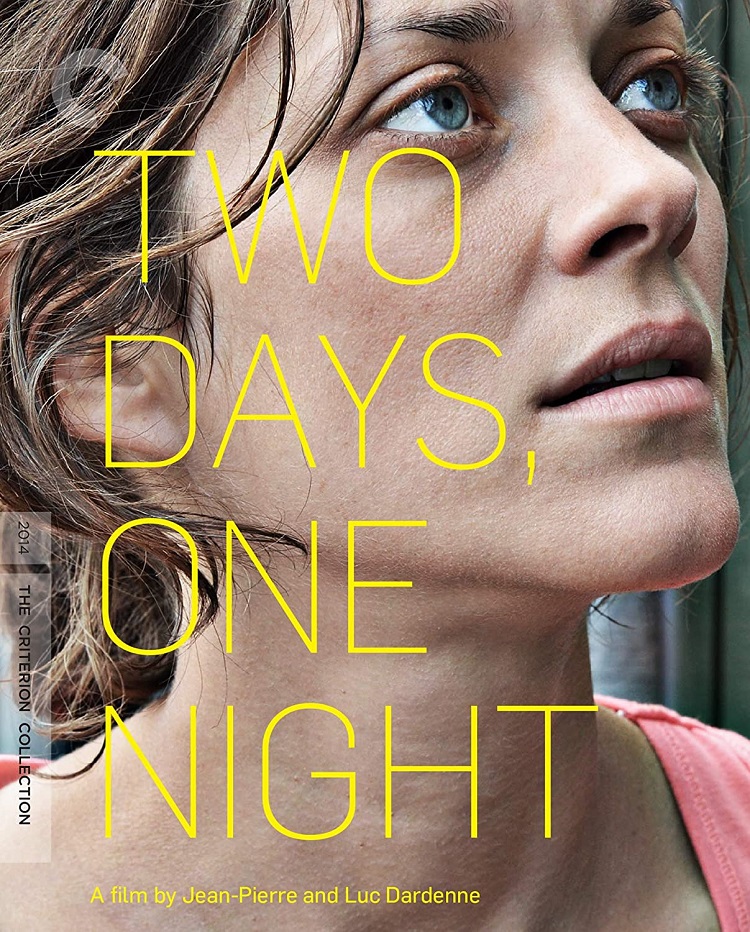

It is, as one might imagine, an emotionally devastating film. In the hands of a lesser actor, it could easily go off the rails into melodrama, but in the hands of Marion Cotillard it is sublimely beautiful. Hers is the greatest performance I’ve seen on the screen in quite some time. She renders such depth of emotion with subtle movements and slight facial expressions.

One of the more powerful scenes finds her and her husband (Fabrizio Rongione) in the car driving to another house where she must beg for her job. Having just been rejected, she’s ready to give up. A sad song plays on the radio and the husband turns it off. Sandra gets onto him saying he doesn’t need to protect her from every sad thing. He turns the radio back on. and she turns it up with a defiant smile. The camera stays on her and we watch her go from playful ruefulness to recognizing how daunting her task really is and back to reasonable hope that she can tackle this challenge with her loving family by her side. She speaks no words but we see all of these small changes in her mental state reflected in her face.

Time and time again, Luc Dardenne and Jean-Pierre Dardenne direct the film with lingering shots of her face and we see a world full of thoughts and emotions in simple smiles or a tiny glance. The Dardenne brothers are noted for their use of realism in their films and it is the same here. This is a simple story made all too real by the continual stomping on human rights by corporations the world over. As such, the pacing is deliberately slow and the camera work moves without any flash. But the very human story at the heart of it, coupled with some extraordinary acting, makes Two Days, One Night an extraordinary and important film.

This is a relatively new film (it was released in May 2014) and as such it didn’t need any real cleaning up, but the 2K digital transfer was supervised by the directors. It’s a beautiful print, though as the film was shot in a naturalistic style, it’s not necessarily pretty. I did not notice any errors or problems in the video at all. Likewise, the audio is very natural, but I had no problems understanding the vocals or hearing any aspect of the film.

Extras include some relatively thorough interviews with the Dardennes, Cotillard, and Rongione; a 45 minute documentary about the directors from 1975; plus a feature on the various location shoots; a video essay by critic Kent Jones; and a written essay by critic Girish Shambu. It’s all very informative and gives some good insights into the film.