Italian filmmaker, poet, philosopher, writer, and sometimes actor Pier Paolo Pasolini has certainly generated his fair share of controversy. He’s probably best known to mainstream culture for his Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom, a film our own Gordon S. Miller considers the “most repulsive” film he’s ever seen. Not for nothing, but that’s likely no small feat.

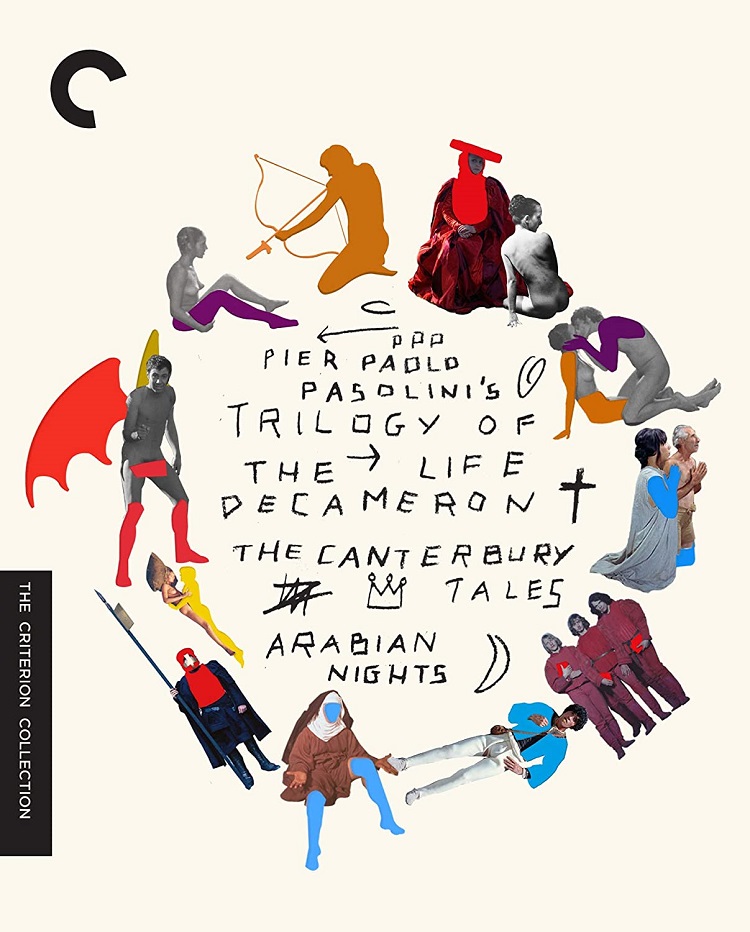

Prior to the repulsion of Salò, Pasolini actually made a few less disturbing motion pictures – but they were no less controversial. His Trilogy of Life envelopes three films, each of which deals in a different piece of medieval literature. Thanks to the good folks at Criterion Collection, the trilogy is now available in one lovely box set.

The first film is The Decameron from 1971. This visually earthy motion picture finds Pasolini filming in the language of Naples rather than more mainline Italian, a nod to the more provincial aspects of his moviemaking. His desires to connect with the people of lower income classes and to thumb his nose at the bourgeois are present in every frame of most of his pictures and The Decameron is no different.

The picture is of the realistic vein, pulsating with bawdiness and sex. Based on Giovanni Boccaccio’s 14th century moral tales, The Decameron is Pasolini’s way of parsing the original work – so to speak. There were 100 tales in Boccaccio’s vision; the filmmaker covers ten, eliminating the stories that deal in kings or nobles in favour of works pertaining to peasants and work class people.

There are a number of highlights, including a story told “in the Neapolitan way” about a convent full of horny nuns. They think they’re using a deaf-mute for their sexual exploration, but a surprise causes them to call to something even more miraculous. There’s also a tale involving a grinning, toothy cuckold and his wife, the latter of whom uses the sale of a “jar” to scratch an itch.

The second film is The Canterbury Tales. This features Pasolini as Geoffrey Chaucer and runs through eight of the 14th century stories. Written in Middle English initially, Pasolini’s take on The Canterbury Tales is darker and more personal. There is still plenty of bawdy content, of course, and there are the requisite fart jokes.

But The Canterbury Tales seem to have unlocked something more profound in the mind of the Italian. The blasphemy and the capitalistic critiques still resonate, but it’s hard not to cringe a little when he invokes the opening tale of a man burned to death for sodomy. His own sexuality wasn’t much of a secret and there seems little doubt that his preoccupation with it on a moral level (as well as a commercial level) is presented in this sequence.

At the same time, this darker set of tales is presented seemingly “for the pleasure of telling them.” Pasolini, evidenced in sequences like the tale of the miller, seems to go for more humorous angles without much hesitation. These scenes play more like farce than anything deeper, stories told because they bring a sense of lewd delight.

The third and final film in the set is Arabian Nights. This is the most exotic film. The 1974 picture saw Pasolini travel to Nepal and parts of the Middle East and Africa, including Yemen. Arabian Nights takes on tales from One Thousand and One Nights, the volume of folk tales taken from the Islamic Golden Age. Like The Canterbury Tales and The Decameron, these stories give Pasolini the opportunity to introduce his own views of classic literature.

In this film, Pasolini seems more interested in structure and even offers a framing tale that involves a young man falling in love with a slave girl. This sets the foundation for what is essentially a joyous film about sex; the commodity of the thing that so haunted the other two pictures in the trilogy is replaced by something more innocent and yet no less ribald.

Arabian Nights is also the most ambitious picture in the trilogy, with his location shooting formulating some truly remarkable visual feasts. This seems to mesh with his conceptions of innocence, illustrating young bodies in all sorts of forms of sexual ecstasy against a backdrop that Pasolini seems to consider more innocent and less tampered-with by the crimes of capitalism.

Criterion Collection has really done a nice job on this set, providing each picture as a new digital restoration for Blu-ray. The colours are rich and sumptuous, with very little by way of image issues throughout each picture. Sound is also on-point, with the films taking their audio cues from an uncompressed monaural soundtrack.

There are many bonus features for each film and a booklet that includes insightful essays from critic Colin MacCabe and an ironic work called “Trilogy of Life Rejected” by Pasolini himself.

The Decameron includes a visual essay from film scholar Patrick Rumble that proves especially enlightening, as well as a 45-minute documentary entitled The Lost Body of Alibech that concerns a lost segment from the film. Another 25-minute documentary based on archival footage covers some of Pasolini’s broader views.

The Canterbury Tales features an interview with scholar Sam Rohdie as well as a 47-minute documentary about Pasolini and Chaucer that is presented by Roberto Chiesi. New interviews with Ennio Morricone and art director Dante Ferretti are also fascinating.

Finally, Arabian Nights packs an introduction by the director as well as a visual essay from film scholar Tony Rayns. There are also some deleted scenes and a 16-minute documentary that features Pasolini and Italian documentarian Paolo Brunatto.

From the glorious box art to the bounty of features, the Trilogy of Life really is a blockbuster release from Criterion Collection. Pasolini fans will find this an obligatory part of their collection, while those who’ve been frustrated by the filmmaker may find a more palatable and less abhorrent side at play here.