There is no way that someone could direct a documentary such as Katrina Babies the same way if they had not witnessed the event firsthand. First-time director Edward Buckles Jr. was only 12 when Hurricane Katrina struck his hometown of New Orleans. There were thousands of others that experienced the same horrific event, and many of them were still in high school or even younger. Buckles does the smart thing by gathering several of them, mainly people to whom he is close, and brings them in to share their experiences.

Through archival news footage, Buckle has the viewer vividly relive the nightmare that was Hurricane Katrina. The aftermath where homes are destroyed or heavily damaged is still riveting to witness. Buckle also culls together old photos and home movies from either his family or the interviewees. It’s a well-assembled and well-put-together documentary. Unfortunately, there are some directorial decisions that make Katrina Babies lose that initial intrigue and don’t fit the message of the documentary.

Buckles discusses how, after the hurricane hit, very few of the young survivors were asked how they were doing. It seemed like they had been the forgotten ones in all of this. For kids between the ages of 3 and 18 that are featured and that experienced it, they’re upfront in their revelation that they were traumatized. They know that their lives would never be the same, and they didn’t feel like there was enough of a support system. The documentary goes into deeper details about how kids were getting into more fights in school or resorting to other poor life decisions that would get them into a lot of trouble. It’s tragic and heartbreaking to hear, especially when the words are coming from the mouths of those whose lives were altered.

There are moments where Buckles narrates and has paper mache-like animation to accompany the narration. This is most likely due to the fact that there weren’t enough photos or videos to go along with it, which is understandable. But the paper-mache animation takes the viewer out of the moment. It becomes a major distraction to the narrative.

Another factor is when Buckles makes the point that many families were displaced after Hurricane Katrina. This is a true statement, and one that is solidified by the archival footage of thousands of people gathered around one area waiting for assistance and government workers taking kids away. But then Buckles makes the comment that this moment in which families were heavily displaced was on par with slavery and how many families were displaced during that time. This type of messaging is off-putting and doesn’t serve the documentary any good.

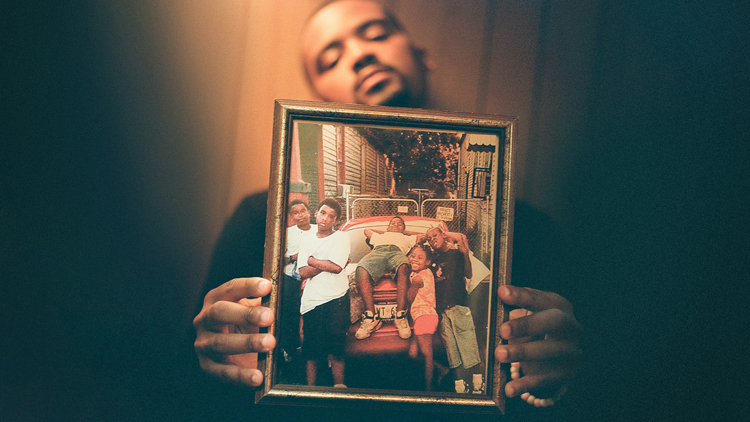

Before Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans was an area in which the neighbors knew each other and the community was thriving with friendships and get-togethers. Witnessing the culture be alive during this time is incredible to behold. The viewer gets a sense of yearning from Buckles that he wants that time to come back. It’s also something that those who never got to experience it themselves would want to witness firsthand.

Buckles explores how the government’s response to the aftermath was atrocious, which is an understatement. One example that happened was when trailers filled with high levels of formaldehyde were escorted over to the area for evacuees to take shelter. No one knew of the formaldehyde issue, and many were left with serious health problems. One girl in the documentary talked about how she developed a tumor because of the trailer in which she stayed.

As a collection of personal accounts, Katrina Babies is raw and hard-hitting. You can feel the pain in the interviewees’ voices as they recall the incident and what happened afterward that turned New Orleans into some place that is completely different than what it used to be. Crime, violence, and other negative factors have now plagued the area, and most of the victims or suspects are people that experienced Hurricane Katrina at a young age and never received the proper care. But what holds it back is the unnecessary attacks that compare certain elements to slavery or how the housing development looks more upscale than their once urban areas and how white people took over the neighborhoods in which they used to live.

I get the anger and the frustration. I get how losing what was once your livelihood can change you, and how it seems that everything you once held is now gone for good. But with the way Buckles approaches the issue in Katrina Babies, there are some criticisms that come off as misguided attacks toward things that are out of his control. It’s a well-intended documentary, but it loses its impact when it makes statements that are unrelated to the story.