It’s easy to forget just how great a film actress/screen presence Lily Tomlin can be. In part, she’s a victim of her own versatility and staying power as a multi-platform performer. She’s been making us both laugh and think on TV, stage and screen since the 1960s; she first impinged on my baby boomer consciousness on Laugh-In, iconic as Ernestine the telephone operator and six-year-old Edith Ann, blowing raspberries at the audience from her oversize rocking chair.

She’s in almost every frame of Paul Weitz’s film Grandma in the tailor-made role of Elle, a minor poet still mourning the loss of her longtime companion Violet without sacrificing a bit of her feistiness, feminism, and fierce, funny anger. If the story around her is a little too perfectly constructed – it has all its parallels and metaphors set in place, like a carefully charted New Yorker short story – it’s redeemed and humanized by Tomlin’s truth and integrity, along with the skill of the well-chosen supporting actors.

The plot kicks off when Tomlin’s teenaged granddaughter Sage (an excellent Julia Garner) arrives in the morning seeking $600 for an abortion she has scheduled for 5:45 that afternoon. She has come to Elle not only because hip grandma is less likely to be judgmental, but because she quite reasonably fears her uptight mom (Marcia Gay Harden) would be judge, jury and executioner if she found out about Sage’s condition. Unfortunately, Elle is cash-poor, and has cut up her credit cards and turned them into wind chimes. “I’m transmogrifying my life into art,” she explains, and Tomlin delivers the line with just the right mix of hippie pride and self-mocking rue.

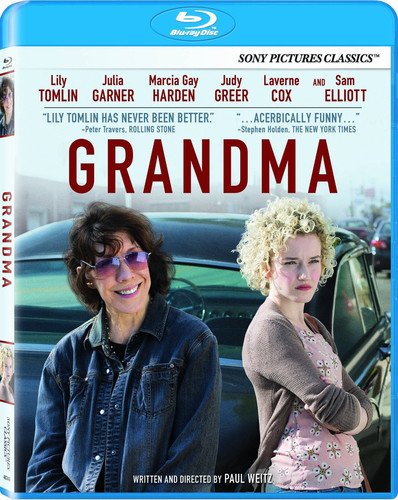

So Elle and Sage begin a trip around town in Elle’s vintage, unreliable Dodge in search of the cash, encountering everyone from the loser baby daddy (Nat Wolff); Elle’s just-dumped younger girlfriend (Judy Greer, the voice of Cheryl on TV’s best animated series Archer); and even Elle’s long-ago male lover (Sam Elliott, still rocking that sexy, masculine voice that now sells Dodge Ram trucks and Coors beer). Other stops along the way include characters brought to life by Laverne Cox of Orange is the New Black and the late, great Elizabeth Peña.

The sensitive, straightforward direction by Weitz, who also wrote the screenplay, helps you forgive the story’s artifice, such as its ticking time limit and the coincidences that push Elle further and further out of her comfort zone and into an eventual confrontation/reconciliation with her own daughter. Grandma also remains clear-eyed about Sage’s right to have an abortion without losing sight of the losses such a decision entails for everyone concerned. The film is touching about the pain of loss, but is saved over and over from sappy sentimentality by refreshing injections of acerbity.

Tomlin and Weitz make sure Elle isn’t some plaster hippie saint dispensing feel-good feminist wisdom. She even gets a “karmic boomerang” when she confronts a pint-sized anti-abortion protester outside the clinic that she eventually delivers Sage to. I won’t spoil the surprise as to the nature of Elle’s comeuppance but it’s almost worth the price of admission.

Weitz, whose career encompasses both the lucrative crassness of American Pie and the lovable humanity of About a Boy, here gives Tomlin the space to inhabit a role that could easily have devolved into several flavors of cliché. If the film containing this performance follows its indie film template a little too carefully, there are far worse crimes a storyteller can commit.