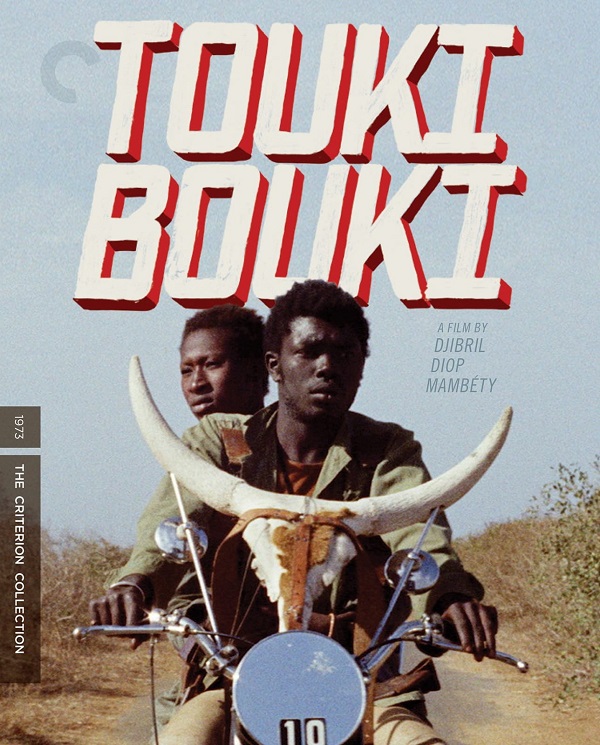

I must admit that African cinema usually goes way over my head. I mostly gloss over it in favor of other types of films and genres. That’s unfortunate because I obviously miss out on powerful and stark portraits of life, love, struggle, politics, and the overall human experience. Djibril Diop Mambety’s acclaimed 1973 masterpiece Touki Bouki, an uncommon and unique fever dream, is definitely one of those films, even if it takes some familiar turns.

The premise centers on a couple, Mory (Magaye Niang) and Anta (Mareme Niang, no relation), two youths in Dakar, who are tired and fed up with living in poverty and their mundane existence. They dream of leaving their homeland to escape to Paris where they can prosper in wealth and luxury. They obviously don’t possess the resources or means of getting there, so they resort to thievery and petty crimes (stealing money and clothing), so they can book passage to Paris for their desired way of life. When they actually get to the ship to take them there, Mory suddenly has a change of heart and runs away, leaving a confused Anta to take the trip alone. The last moments of the film has Mory sitting and staring at his beloved motorcycle, wrecked beyond belief by a rider who stole it.

As I mentioned at the end of the first paragraph, the familiar turns represent that the story isn’t exactly original. It has been told time and time again. However, the way Mambety lets the story unfold (through avant-garde imagery and unconventional editing with an almost music video-like structure), it actually becomes a universal tale of wanting a better way of living, but sometimes having to tread dangerous waters to make those seemingly attainable dreams come true. Personally, I can really relate to this, but I’ll spare you those details.

Originally only included in Volume 1 of Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project, Criterion has made this landmark film available on its own, including some decent supplements: a 2013 introduction by Scorsese; a 2013 interview with filmmaker Abderrahmane Sissako; a 2012 conversation between musician Wasis Diop (Mambety’s brother) and filmmaker Mati Diop (his niece); and Contras’ City, a 1968 short film/travelogue by Mambety (restored in 4K). There is also a wonderful new essay by film programmer and critic Ashley Clark.

Despite a few weird choices and some maybe unnecessary animal cruelty, I overall found Touki Bouki a genuinely profound tale of individualism, freedom, and longing, with some moments of jagged humor and surrealism to help keep the film grounded and close to reality. It may not be everyone’s cup of tea, but it is a film that deserves to be seen and discovered.