As Luis Buñuel neared the end of his life, he swore each time he made a film that it would be his last, not because he wanted to quit, but because he feared dying before completion. Known as Don Luis to his crews and cast members, he reportedly made his sets welcoming, joyous environments, even as he grappled with his own mortality. Death factors into the plots of each of the films included in this new Criterion box set, but Buñuel’s wry comedic sensibilities ensure that the films never seem morbid, instead seemingly implying that life is but a farce.

Of the three films, the first two are original works, while That Obscure Object of Desire is an adaptation of a novel from 1898 that had been filmed many times before, most notably in a 1929 version that had a major impact on young Buñuel, appearing in the same year as his debut directorial effort. In fact, one of Criterion’s best bonus features here shows key scenes from that 1929 silent film, La femme el le pantin, making it easy to compare just how strikingly similar Buñuel staged those scenes in his own version.

The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972) starts with a simple concept of a group of friends meeting to dine together, but then spins into a cascading series of misadventures and side quests that occasionally totally disregard that idea as Buñuel pursues his artistic muse wherever it leads. At one point, the diners seem to have found an abandoned restaurant they can have to themselves for their meal, only to learn that a funeral is happening in the room right next to them. Odd things happen throughout the film, but they’re surrounded by the banality of the friends going through the expected motions related to securing a meal, with Buñuel seemingly thumbing his nose at societal norms such as when he literally pulls the curtains back on the diners seated at their table to reveal that they’re on stage in front of a live audience.

The Phantom of Liberty (1974) disregards expected structure even more, eschewing any overarching plot in favor of a loose collection of 12 seemingly unrelated vignettes with only certain characters moving throughout them to tie everything together. It’s the funniest film of the set, as well as the most confounding. It starts with a firing squad set centuries in the past, then moves on to the present day as a creepy man approaches a couple of young children in a park and offers them a collection of photographs, leading to an uncomfortable situation when they arrive home and show the pictures to their horrified parents, with the parents throwing a fit about each of the seemingly more obscene images that are revealed to be totally innocuous shots of nature and architecture. Later, there’s an extended sequence where parents are called to their daughter’s school because she has disappeared, leading to a trip to the police station and a desperate missing persons search, all while the little girl is right by her parents’ side, with the police captain interviewing her as he fills out the missing persons form. It’s a wacky, subversive film, clearly showing that Buñuel still had the chops of a young rebel even as he entered his mid-’70s.

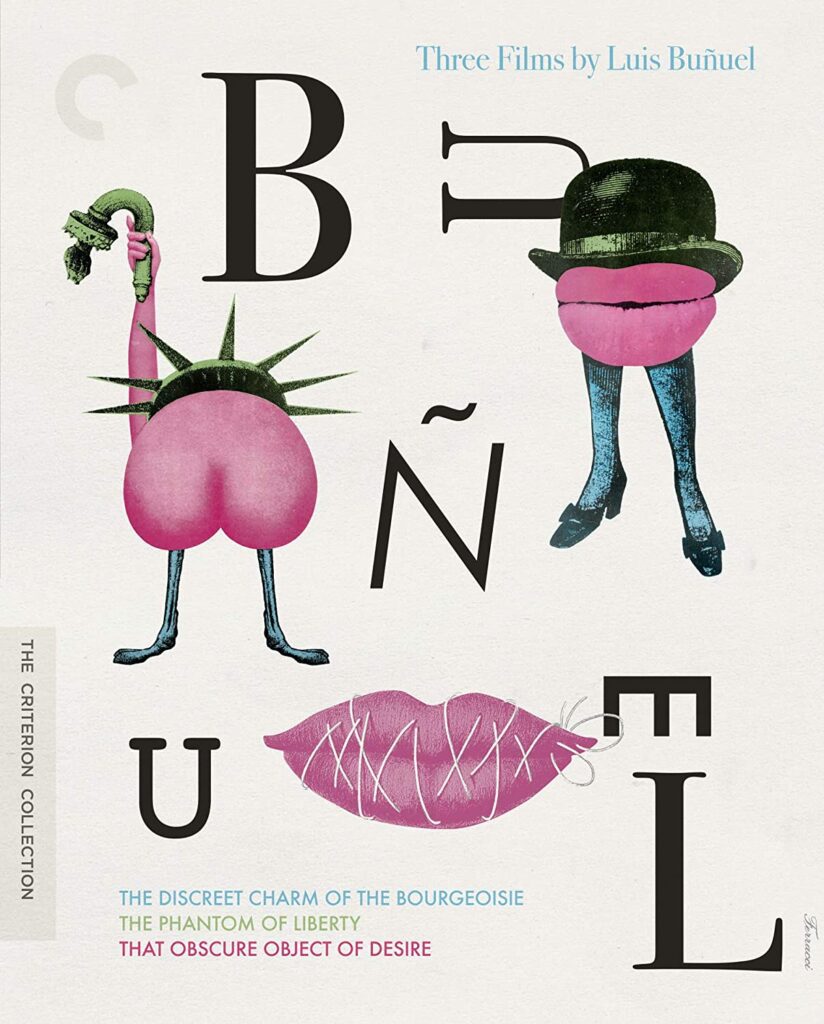

That Obscure Object of Desire (1977) returns to classic plot structure, with Buñuel’s adaptation mostly coloring within the lines aside from starting and ending with literal bangs. His most subversive act here is the dual casting of Carole Bouquet (For Your Eyes Only) and Angela Molina as the principal female character, switching them out at random, even mid-scene. They aren’t physically or culturally similar, he just got a kick out of the idea and went for it, renewing his passion for his final film after he initially shut it down in the wake of his displeasure with original casting choice Maria Schneider (Last Tango in Paris). The story is about an old man who becomes infatuated with a young woman, following her around like a puppy even as she initially rebuffs his advances. The plot isn’t all that interesting, but Buñuel’s execution is exceptional, exploring the pathology of desire as he delivers a cohesive, moving adapted story as he did to similar fantastic effect with Belle de Jour. It’s a fine coda to his monumental career and Criterion’s excellent box set.

All three films feature new digital transfers in their original aspect ratio of 1.66:1. They were all created in high definition from 35mm interpositives and 35mm magnetic tracks, and they are uniformly lovely with no evident degradation or defects. Colors are slightly washed out as typical of 1970s films, but the image clarity and consistency are top-notch and the monaural soundtracks exhibit peak fidelity.

The box set is stuffed with so many archival bonus features that they become a bit repetitive, with duplicate anecdotes and comments on Buñuel’s technique. Still, there’s a wealth of fascinating information to be found in the many features, as well as evidence of a fountain of youth based on the interviews with the still-luminous Carole Bouquet and Angela Molina filmed 40 years after their appearances in That Obscure Object of Desire. Other highlights are a freewheeling 1977 roundtable discussion with many of Buñuel’s collaborators, a 1985 documentary about Buñuel’s frequent producer Serge Silberman (responsible for all three films in this set), and Speaking of Buñuel, a documentary from 2000 about Buñuel’s life and work. The large volume of bonus features paired with the three provocative films make this a virtual film school in a box, a superior addition to the collections of Buñuel aficionados as well as any viewers looking to gain insight into his masterful final works.