Written by Kristen Lopez

A trio of amazing Twilight Time releases arrive, worthy of your hard-earned money.

Romeo is Bleeding (1993)

When they say “love is blind,” I doubt it extends to the utter blindness exhibited by small-time crooked cop Jack Grimaldi (Gary Oldman) in Peter Medak’s 1993 neo-noir. The story of a cop’s attempt to kill a vicious Russian assassin, Mona Demarkov, (played by a scantily clad Lena Olin) has an ironic sensibility to it in today’s day and age. Upon first glance Olin’s sexually aggressive assassin isn’t the best depiction of femininity, especially when coupled with the camera’s need to showcase her backside, but Olin makes the character crazed and brilliant. Her resourcefulness is so ingenious even Jack can’t ascertain how she escapes everyone’s clutches. Both Jack and Mona are two peas in a rotted pod, who almost enjoy their cat-and-mouse banter as much as Jack detests the man he’s become. Like any good noir, our hero is so flawed as to be an out-and-out villain and who better to portray him than Oldman, who allows himself to became battered, blood-stained mess by story’s end. But it’s impossible to ignore Olin when all is said and done. Pure sex, Olin’s gleefully maniacal laugh will haunt your dreams.

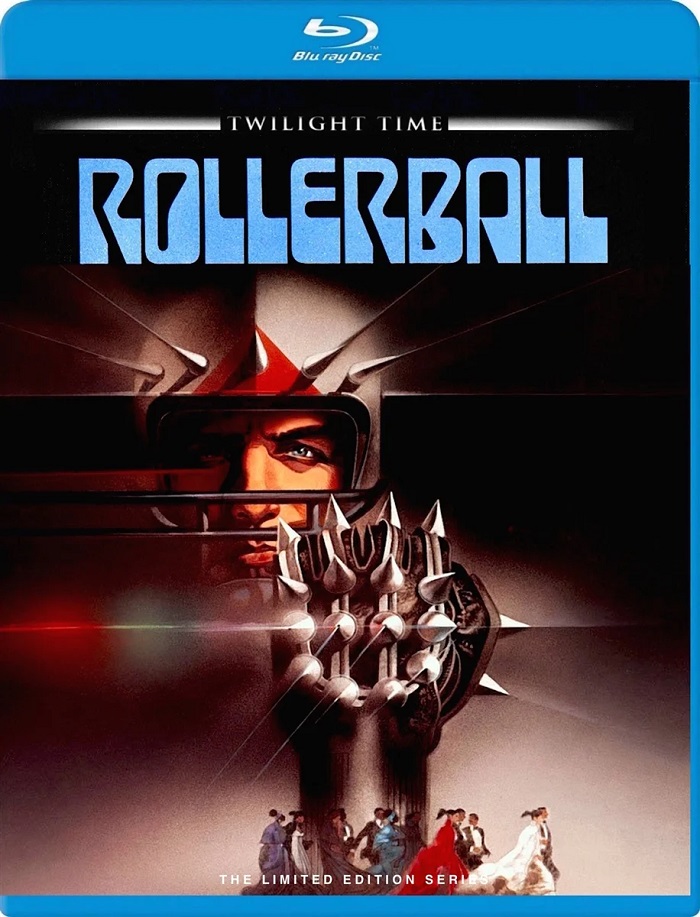

Rollerball (1975)

One sure way to know civilization has changed, whether it be in The Running Man or The Hunger Games, is if entertainment is co-opted and players are placed on a gameboard where the rules are in favor of their assured destruction. A more prominent entry in this genre is Norman Jewison’s 1975 film Rollerball. In 2018, men play a combination of rollerderby/pinball/basketball for prestige and material possessions. Unlike other sci-fi films with similar premises, Jewison and screenwriter William Harrison present a sparse tale of the individual triumphing over the corporation/government. There are deeper depths to be mined with regards to the 1970s views of consumerism, feminism and government interference, but Jewison and crew don’t want you to think on things as opposed to presenting them.

In between fast-paced scenes of chaos on roller-skates, prominent player Jonathan E. (James Caan) tries to figure out why he’s being forced to retire from a game he loves. Unlike Logan’s Run or Soylent Green there isn’t a grander conspiracy at work that we’re privy to, but an emphasis on Jonathan’s own personal quest for individuality. With a quiet presence the film vacillates between moments of high-octane action and dialogue scenes. I’m still unsure whether I bought Caan’s character. Oftentimes he looks confused or numb. John Houseman is delightful as the head of the energy corporation in Houston. Rollerball is certainly unique, but the lack of world-building and society outside of the arena limits it from being a classic.

Inserts (1975)

As Julie Kirgo’s essay states, Hollywood went mad about itself in the 1970s, or at least the version of itself from the 1920s and 1930s. This subgenre of features lifts the veil on the glitzy, highly maintained world of the silver screen in its infancy, thus why these 1970s features tended to skew towards more sex and nudity. John Byrum’s controversial 1975 feature, Inserts, is the skanky cousin of Singin’ in the Rain in that it looks at the dirty road stars who couldn’t hack it in talkies often went down.

A once amazing director known only as the Boy Wonder (Richard Dreyfuss) has lost a once-promising career and finds himself making stag films in his decrepit mansion. Over the course of a day the Boy Wonder learns his actors and his backer provide more trouble than they’re worth, all the while the “new kid at Pathe,” Clark Gable, invisibly keeps dropping by to bring the Boy Wonder back to prominence. Originally slapped with an X-rating, Inserts deftly blends the horrors of the transition from sound to talkies with the seamy underbelly that was early porn production.

Richard Dreyfuss is utterly amazing as the drunken sod of a director with such an antipathy towards life he can’t even muster up the interest – and all that that implies – in sex despite being surrounded by it. Veronica Cartwright casts caution to the wind as the Jean Hagen-esque “star” of Boy Wonder’s films, Harlene. Bob Hoskins is hilarious as the backer of Boy Wonder’s movies, desperate to keep his new girlfriend, Cathy Cake (a pre-Suspiria Jessica Harper), away from all the degeneracy. With blinding wit and some explicit sexuality, Inserts is unlike the other Hollywood tales of the era in that there appears to be a method to the madness, steeped in frank discussions of sex that takes off with regards to the gender issues that grew to a crescendo in the late-’70s.