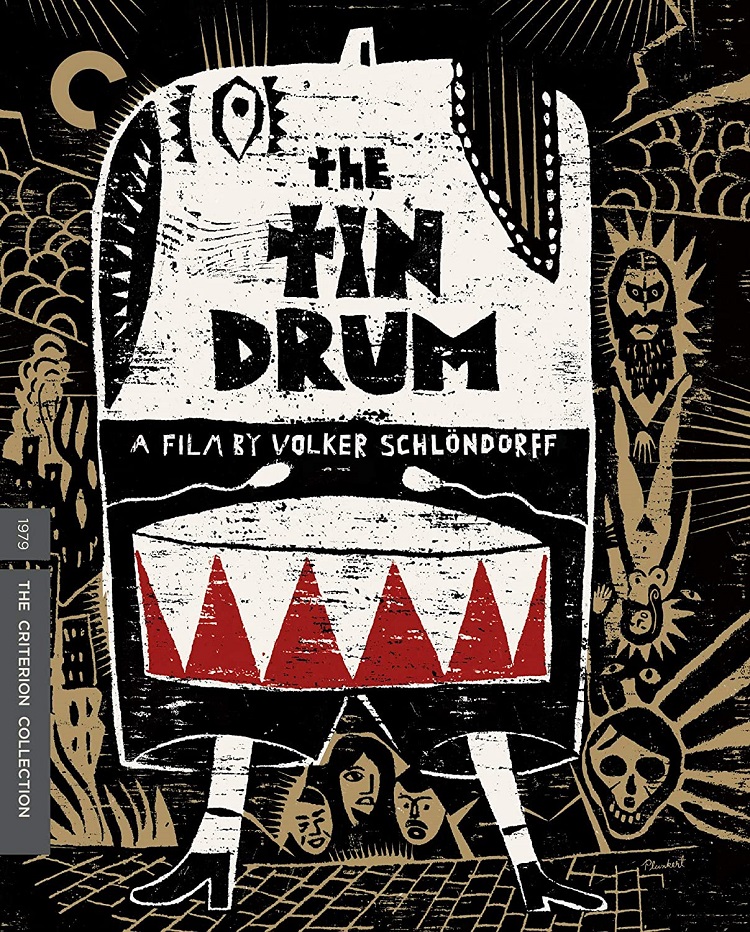

For a film that won both the Palme d’Or and the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, The Tin Drum (1979) faced a huge outcry when it was screened in the United States. The Criterion Collection have just issued a two-DVD Director’s Cut of the film. After viewing it, I cannot say that I am surprised at the furious reaction. The movie is a very artistic, at times even pretentious adaptation of the novel by Gunter Grass. But there are scenes in The Tin Drum which I found very difficult to watch.

The story revolves around young Oskar Matzerath (David Bennett), who grows up in Nazi Germany. Actually, “grows up” is not quite correct, as Oskar is born with the intellect of an adult, but decides that he will not physically develop past the age of three. He accomplishes this by throwing himself down a flight of stairs on his third birthday, which somehow stifles his growth. The other big event that happens when he turns three is the gift of the titular tin drum. Over the course of the film, many people will attempt to separate Oskar from his drum, and all will fail.

Oskar may be the main focus of tale, but the weird behavior he engages in is hereditary. In the opening scene we see his grandmother alone in a huge field, cooking potatoes over a fire. A man is running from a group of soldiers, and she hides him under her vast skirts. They later marry, and the woman gives birth to Agnes (Angela Winkler), Oskar’s mother. The idea of a woman hiding a guy under her skirt from soldiers, then going on to marry him is a little unusual, but is nothing compared to what follows.

The soldiers were chasing Oskar’s grandfather because he is a known arsonist. When he is cornered at a waterfront, he jumps in, and Oskar explains that he was never heard from again. Most people thought he drowned, but there is a rumor that he lived a long and prosperous life in the U.S. According to this tale, he has made his fortune by selling wood, matches, and fire insurance to the unsuspecting Americans.

Back at home, young Agnes becomes sexually involved with her cousin Jan Bronski (Daniel Olbrychski). Up to this point, the movie had struck me as an offbeat study of an unusual family. The incest business changes the tone considerably. During the first World War, Agnes works as a nurse, and meets and marries a young soldier by the name of Alfred Matzareth (Mario Madorf). Oskar is given Matzareth’s last name, but apparently Agnes was already pregnant by Jan when she wed.

All of this happens in the first 20 minutes of the 163-minute film, and sets up an unrelenting tone of absurdity, which is basically the whole point. I imagine there are many levels that director Volker Schlondorff intended for his audience to uncover, but I am not certain that this is even necessary. Oskar’s family and life are obviously metaphors for the rise of the Nazis. He is born during World War I, and while fully cognizant from birth, he never physically develops beyond the age of three. You can throw in all the dwarfs, crazies, and authority figures you want, but they are all there for the same reason, to reinforce the sense of madness.

The Tin Drum plays out like a fever dream. The love triangle between the Matzareth’s and cousin Jan is joined by the Jewish toymaker Sigismund Markus (Charles Aznavour). Sigismund is Oskar’s supplier of tin drums, as he seems to break them with remarkable frequency. He is in love with Agnes, but meets his maker during Kristallnacht.

The craziness continues unabated though, as Agnes develops an insatiable craving for raw fish, and dies of food poisoning. Jan is killed by the SS at the Post Office. At this point, Oskar has turned 16, and it is down to just him and Alfred. The two are working in the family grocery store, and Alfred soon hires the 15-year old Maria (Katharina Thalbach) to help out.

It was with the arrival of Maria that The Tin Drum crossed the line for me. I found the scenes in which Oskar seduced Maria to be repulsive, matched only by those of Alfred doing the same thing. Maria eventually gives birth to Oskar’s child, who is given the name Kurt.

There is constant danger in the occupied city, and in the final chapter of the film, Alfred is killed. At his funeral, Oskar slips and falls into the grave, and little Kurt throws a rock, which hits his father on the head. With this event, Oskar begins to grow again, and most of the family are deported. All but Oskar’s grandmother leave on a train, and the film ends as it began, with her sitting alone in a potato field.

I have not had the pleasure of reading Gunter Grass‘ book, so I have no idea how faithful the film is to its source. Since Oskar addresses the audience from the very beginning as an adult, I would think that the scenes between him and Maria having sex would not be as troubling as they are onscreen.

When The Tin Drum was filmed, David Bennet was 11, and looked much younger, and Katharina Thalbach was 24, but easily passed for 15. Call me a prude if you like, but I found that watching these two children having sex to be way beyond my comfort zone. It kind of made me sick, to be honest. In the book, it probably worked, but actually viewing it is something else entirely.

The first Criterion Collection DVD of The Tin Drum was released in 2004, and included a bonus feature titled Banned In Oklahoma. The piece documented the banning of the film in Oklahoma City, which was finally resolved in the director’s favor in 2001.

With the 2013 release of The Tin Drum, Criterion has made a bit of a trade-off. The 2004 DVD presented a cut of the film which ran 142 minutes. The newly released Director’s Cut adds 23 minutes of footage, for a running time of 163 minutes. Unfortunately, Banned in Oklahoma is not included in this package though.

The second DVD of the set does feature quite a bit of supplemental material however. The most significant of these is an interview with director Volker Schlondorff, conducted in 2012. Over the course of the 67-minute sit-down, Schlondorff discusses The Tin Drum in depth, including the Oklahoma banning. Continuing in this vein is another 2012 interview, this one with the German film scholar Thomas Corrigan. Among other topics, Corrigan puts The Tin Drum in perspective, in regards to the history of German cinema.

“The Platform” is a scene from The Tin Drum during which Oskar disrupts a Nazi rally with his drumming. It is accompanied by an audio recording of Gunter Grass reading the corresponding passage from his novel in German (eight minutes).

The final segment is comprised of four television interviews. The first is with actor Mario Adorf and co-screenwriter Jean-Claude Carriere regarding their experiences with the picture (four minutes). The next is with actor David Bennent and director Volker Schlondorff at Cannes in 1979 (four minutes). “On Location” is an interview with the director, conducted during the shooting of the film (four minutes). Schlondorff is the subject of the final interview as well, which took place just after he won the Palme d’Or (two minutes).

There is also a booklet included, with essays from film writer Geoffrey MacNab and Gunter Grass himself. Both provide fascinating insights into the film, and in particular what Grass thought of the adaptation.

I am fully aware that my reaction to the child-sex in The Tin Drum puts me on the “wrong” side of the issue, but that is too bad. I must clarify that the sex is not explicit, but there is no mistaking what is going on. The scenes are also very brief. As I mentioned previously, I think that in the book this material was probably not nearly as disturbing as it is when you view it. From the very beginning, the tone of Oskar’s voice is much more “adult” and mature than that of just about every grown-up in the picture. But actually watching this 11-year-old boy and young girl engage in carnal knowledge is something completely different.

So there is no denying that I had difficulty with some of the sex in The Tin Drum. As far as banning the film goes though, I do not believe in any form of censorship. There is no question that The Tin Drum is an important piece of work, which the high honors it received testify to. With this Director’s Cut, Criterion have offered film buffs the ultimate edition of The Tin Drum, and are free to draw their own conclusions.