Kiku (Shotaro Hanyagi) is the adopted son of Kabuki royalty in Tokyo. As the presumed heir to this theatrical throne, he is constantly lavished with acclaim. The mouths that herald his praises come with two faces and out of the other, they spit ridicule. Even Kiku’s father-in-law cannot bring himself to tell him how poorly he acts. Late one night, he walks with Otoku (Kakuko Mori), nursemaid to Kiku’s brother’s son, who finally tells him the truth – he stinks! Instead of lashing out in anger, Kiku’s is filled with gratitude that someone is finally willing to speak to him honestly. Otaku thinks he has talent but he needs to take his craft seriously and work on his art instead of carousing with women every night.

The two become close, developing an intimacy that is not allowed in 19th century Japanese social customs. When she is fired by Kiku’s mother, he runs away to Osaka, changes his name, and begins working for a smaller, less prestigious theater group. Eventually, Otaku joins him and they form their relationship into a common-law marriage. Otaku works herself ragged trying to make ends meet so he can improve his art. Still, his acting isn’t good enough to stay employed by the Osaka troupe so he must travel to the countryside villages with a traveling theater, making even less money than before.

Otaku stays by his side, giving up everything she has for him. She works at any job she can get, day and night, so that he can remain an actor. In one of the film’s more moving and technically brilliant scenes, we see her staying below the stage while he performs, praying for him. The film cuts between the two, showing us exactly what she’s given up and what he has gained. Eventually, he rejoins with his family and the majesties of the Tokyo stage as a great actor. But it comes as a cost. Otaku has literally worked herself sick and can no longer join him in his returning glory.

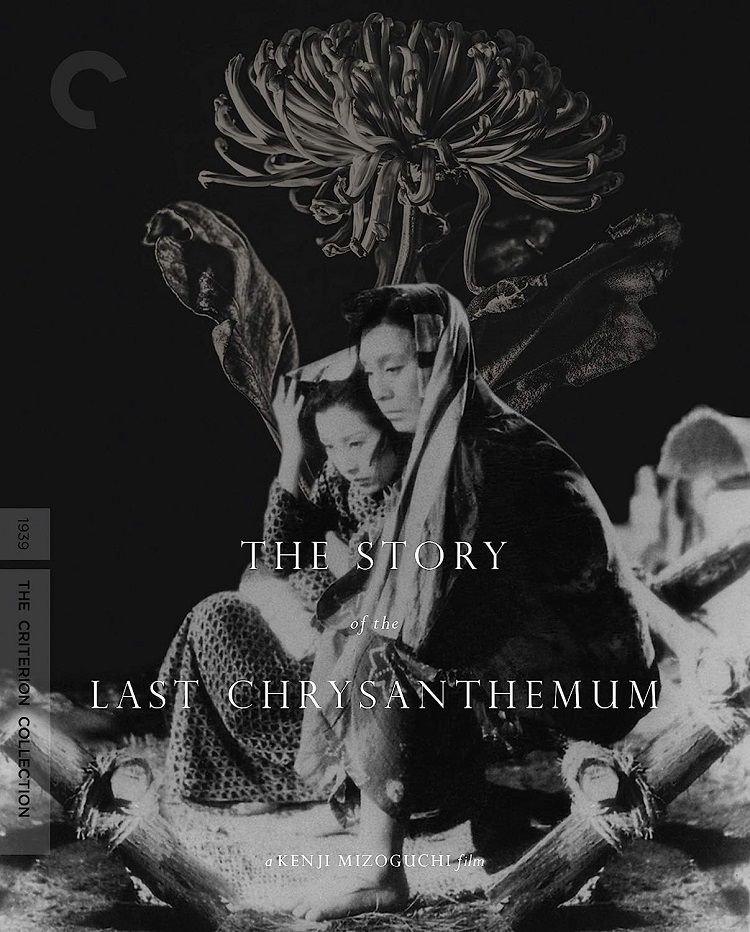

By the time director Kenji Mizoguchi made The Story of the Last Chrysanthemum in 1939, he had already made some fifty films (most of which, unfortunately, have been lost to time) but it is with Chrysanthemum that he began to fully develop his signature style (long takes and intimately detailed mise-en-scène compositions). He often places his camera at a distance, eschewing coverage shots (close-ups on the actors’ faces as they converse) for longer master shots. This makes the audience a voyeur – gazing into very intimate moments from the outside. Often the camera will do a long tracking shot, moving from one side of a room to the other, slowly taking in the action all around. Early on, he uses a shot like this to show some theater goers praising Kiku to his fact and then following them into another room where they ridicule him outside of his hearing.

It is a masterfully made film, if not always an interesting one. Kiku and Otaku’s love story is a moving one and Mizoguchi has a lot to say about class relations, Japanese society’s treatment of women, and the value of art, but it doesn’t always translate to a 21st century American filmgoer’s experience. At least not mine. When I was able to focus on the compositions and the really interesting set pieces, I was enthralled, but when I tried to pay attention to the storyline, I often found myself checking to see how much longer the film had left (and with a 142-minute run time it was often a lot). Still, there is much to love about the film and it is undoubtedly a classic that needs to be seen.

Criterion’s transfer looks quite good all things considered. It runs a shade on the dark side but the overall image balance is good. The blacks, whites, and grays are sharp, and the levels are mostly good, though there is some fluctuations noticeable, especially in the darker scenes. The edges of the film have been worn from time and there are other instances of imperfections. But given the age of the film (and how so many films from this time have been completely lost), I can’t really complain. Sound quality is likewise good considering the limitations of the film.

Extras are a bit slim. All you get are a very nice 22-minute interview with critic Phillip Lopate who intelligently discusses Kenji Mizoguchi’s directorial vision. There is also a nice essay by film scholar Dudley Andrew in the leaflet.

Kenji Mizoguchi went on to direct such masterworks at Sansho the Baliff and The Life of Oharu and is a much celebrated Japanese director. The Story of the Last Chrysanthemum was my first film of his, but it will surely not be the last.