When Koyaanisqatsi (1983) came out, my girlfriend at the time talked me into seeing it with her. She was very much into the art house scene, while I was more of a Wargames (1983) kind of guy. I must admit that upon first viewing the film, I was dumbfounded. There is no dialog or narration at all, rather, it features a compelling series of images which are set to the music of Philip Glass. The movie is very much like a dream, and assumes the audience’s intelligence in deciphering the story that producer and director Godfrey Reggio is telling.

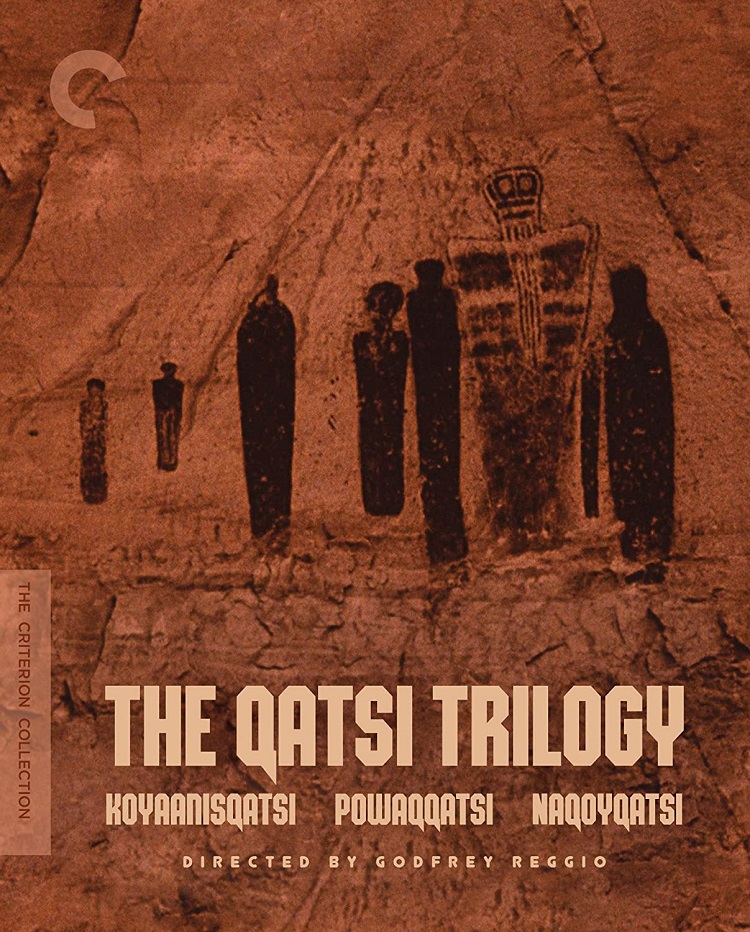

Koyaanisqatsi was the first film of the Qatsi Trilogy, which took 19 years to complete. The two other entries in the series are Powaqqatsi (1988), and Naqoyqatsi (2002). As we approach the 30th anniversary of the first film, The Criterion Collection have released a beautiful triple-DVD box set of The Qatsi Trilogy. Each of the films have been remastered, and are loaded with extras.

The curious titles come from the Hopi Indian language, which Reggio became familiar with as a resident of New Mexico. Koyaanisqatsi translates to “life out of balance.”

If anything Koyaanisqatsi just gets better with age. I may not have fully gotten it in 1983, but there were two reasons for this. I believe that I did not initially understand it due a combination of youth, and the fact that nobody had ever made a movie like Koyaanisqatsi before. Reggio’s film is a visual meditation on the damage he believes our heavy reliance on technology has wrought.

Koyaanisqatsi opens with what appears to be an Indian painting. This dissolves into a shot of a group of people surrounding a man with a crown. In these first few seconds, Reggio presents us with the “noble savage,” then follows it with a shot of a rocket taking off. This is the basic language of the film. We go from scenes of “native” life, complete with beautiful landscapes and natural phenomena, to scenes of urban blight, war, factories, atomic tests, and other ugly examples of “progress.”

Now that I am a bit more seasoned than I was 30 years ago, I see that Reggio hammers us pretty heavily with his anti-technology point. The movie could be called left-wing propaganda by those who disagree with its message, and they would not be wrong. Reggio admits as much in the many supplements. What lifts it beyond propaganda and into the realm of art is the beauty of the footage, and the way Philip Glass’ soundtrack is so seamlessly integrated.

Of the three films in the trilogy, the bonus features for Koyaanisqatsi are the most impressive. The first of these is Essence of Life (2002), a 25-minute piece during which Reggio and Glass discuss their collaboration. In many ways, I consider director of photography Ron Fricke to be the unsung hero of the movie. In a 16-minute interview filmed in 2012 by the Criterion Collection, Fricke explains his role in the process.

“Privacy Campaign” is a fascinating bit of history which explains the origins of the trilogy. Reggio’s first step into activism began in 1974, with the eight commercials that encompass this segment. The spots were produced by the New Mexico Civil Liberties Union, and were designed to bring awareness to issues of invasion of privacy. It is almost quaint in to see this material today, where people willingly give up nearly all of their rights to privacy for the promise of a shinier new cell phone.

The grand finale of the extras is the 40-minute silent demo version of the film, made in 1977. In addition to the silent demo, there are two “scratch tracks” that were made with the help of Allen Ginsberg and Peter Orlovsky. Even though Ginsberg told Reggio that they “worshipped different gods” regarding their views on technology, he decided to help out anyway. Scratch tracks are unpolished audio tracks, intended to give the basic idea of what sounds would go where. The first one runs for 30 minutes, and the second is 16 minutes. Ginsberg’s harmonium playing is very interesting to hear, especially in comparison to what Philip Glass would later record for final inclusion.

The second film of the trilogy is Powaqqatsi, which was released five years after Koyaanisqatsi. Powaqqatsi translates to “life in transformation.” Like the first film, there is something of a “noble savage” introduction to Powaqqatsi. Where Reggio’s earlier effort concentrated (for the most part) on Native Americans, and the natural beauty of the United States, his cameras are focused on the third world for Powaqqatsi. The movie opens with shots of miners toiling away, and carrying baskets of materials down steep hills, all by hand.

Once again, the natural beauty of the land and water is highlighted, and contrasted with the ugliness and squalor of the city’s slums. As far as a “story” goes, that is really the crux of it. There are more contrasts than just country/city, such as that of villagers out fishing juxtaposed with marching soldiers, but the point is pretty much the same as in Koyaanisqatsi. In this case life is being transformed, but it is just a different way of stating Reggio’s basic Luddite thesis.

Lest I sound too cynical, let me just say that I do agree with many of Reggio’s points. But as far as a film plot goes, it is all rather basic. As in each of the three films, what lifts this from polemics and into the realm of beauty are the fantastic shots and the music of Philip Glass. The composer is much more adventurous in the second installment than he was in the first. His use of chanted vocals and varying the dynamics makes far more dramatic soundtrack than he created for Koyaanisqatsi. As anyone who has seen these films will attest, this was a true collaboration between director and musician.

The partnership between the two is explored in depth in the first supplement, Impact of Progress (2002), which runs 20 minutes. Anima Mundi (1992) serves to show another example of how well Glass and Reggio work together. This half-hour film has no political axe to grind. The short is a montage of footage of animals in the wild, with the soundtrack done by Glass. I had never seen this before, and it is excellent.

I found “Inspiration and Ideas” to be one of the most illuminating of all the bonus features in the trilogy. In this 18-minute piece, which was produced in 2012 for the Criterion Collection, Reggio discusses his influences. They shed some light on his thought processes, and include the Marxist theorist Guy Debord, the economist Leopold Kohr, and filmmaker Luis Bunuel.

Another rather fascinating inclusion is a 1989 episode of the New Mexico public television program Colores. In this 18-minute program, journalist V.B. Price interviews Reggio about his vision for the trilogy, 13 years before the concluding chapter, Naqoyqatsi (2002) would be released.

Anima Mundi was the only work realized between Reggio and Glass in the ‘90s, but I believe it was worth the wait for Naqoyqatsi. The final film in the Qatsi Trilogy may be over a decade old, but it is a weirdly futuristic work. The translation is “life as war,” but I think the tag nails it much better, “America is Test Driving the Future.”

Naqoyqatsi differs from its predecessors in that the protest element is mostly absent. Maybe it is just better masked, and I did not pick up on it. Reggio himself describes it as a “visual symphony in three parts.” Part one involves life as we know it giving way to numbers and virtual reality. The second involves competition, especially sports, while the third blasts us into the future. The film and trilogy appropriately end with a vision of traveling at light-speed through the stars, just like being on the bridge of the Enterprise.

If I had seen Naqoyqatsi in 2002, I may have had a different impression of it. But seeing the CGI effects of a decade ago today evokes a very strange sensation. I cannot help but think about The Future Remembered, a book by Paula Becker and Alan J. Stein about the Seattle World’s Fair in 1962. That World’s Fair was all about the future, which unfolded very differently in 50 years than those visionaries thought it would. Think of The Jetsons, and you’ll get the idea.

The computer-generated fractals, and virtual reality scenes seem almost as ancient as The Jetsons. I know that this was not the lasting legacy Reggio had in mind for his final installment, but that is the takeaway for me. I enjoyed the film immensely, and the music Glass composed for it is (again) excellent. One reason for the extraordinary quality of the soundtrack is the fact that it marks the first time Glass worked with cellist Yo-Yo Ma.

The supplements for Naqoyqatsi include “Afterward by the Director,” a 16-minute summation of the trilogy produced in 2012 by the Criterion Collection. There is a seven-minute piece featuring Glass and Ma discussing the experience of their first collaboration, and a four-minute segment about the making of the film with key crew members.

Capping everything is the nearly one-hour “Panel Discussion” which took place after a 2003 screening of Naqoyqatsi at New York University. Panelists include Reggio, Glass, and film editor Jon Kane. The discussion is moderated by music critic John Rockwell. The final piece is a highly informative 38-page booklet, which offers a number of perspectives on this 29-year project.

Criterion have done their usual top-notch job with the Qatsi Trilogy, and fans should be very pleased with it.